Translate this page into:

An Analysis of Levels and Trends in HIV Prevalence Among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Clinics in Karnataka, South India, 2003-2019

*Corresponding author e-mail: elangovan@nie.gov.in

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background and Objective:

Periodic tracking of the trends and the levels of HIV prevalence at regional and district levels helps to strengthen a state’s HIV/AIDS response. HIV prevalence among pregnant women is crucial for the HIV prevalence estimation of the general population. Karnataka is one of the high HIV prevalence states in India. Probing regional and district levels and trends of HIV prevalence provides critical insights into district-level epidemic patterns. This paper analyzes the region- and district-wise levels and trends of HIV prevalence among pregnant women attending the antenatal clinics (ANC) from 2003 to 2019 in Karnataka, South India.

Methods:

HIV prevalence data collected from pregnant women in Karnataka during HIV Sentinel Surveillance (HSS) between 2003 and 2019 was used for trend analysis. The consistent sites were grouped into four zones (Bangalore, Belgaum, Gulbarga and Mysore regions), totaling 60 sites, including 30 urban and 30 rural sites. Regional and district-level HIV prevalence was calculated; trend analysis using Chi-square trend test and spatial analysis using QGIS software was done. For the last three HSS rounds, HIV prevalence based on sociodemographic variables was calculated to understand the factors contributing to HIV positivity in each region.

Results:

In total, 254,563 pregnant women were recruited. HIV prevalence in Karnataka was 0.22 (OR: 0.15 95% CI: 0.16 - 0.28) in 2019. The prevalence was 0.24, 0.32, 0.17 and 0.14 in Bangalore, Belgaum, Gulbarga, and Mysore regions, respectively. HIV prevalence had significantly (P< 0.05) declined in 26 districts.

Conclusion and Global Health Implications:

HIV prevalence among pregnant women was comparatively higher in Bangalore and Belgaum regions. Analysis of contextual factors associated with the transmission risk and evidence-based targeted interventions will strengthen HIV management in Karnataka. Regionalized, disaggregated, sub-national analyses will help identify emerging pockets of infections, concentrated epidemic zones and contextual factors driving the disease transmission.

Keywords

HIV/AIDS

HIV Sentinel Surveillance

Pregnant Women

Prevalence

Trend

Karnataka

1. Introduction

1.1. Background of the Study

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) has been a global public health concern since the 1980s. Globally, the estimated population of people with HIV (PWH) is about 37.7 million in 2020.1 India has the third-largest estimated PWH (2,348,860), of which 42% are females aged above 15 years.2,3 In India, estimations indicate 69,220 new infections and 58,960 AIDS-related deaths in 2019.4 Within India, HIV is highly concentrated in the southern and north-eastern states, and reports suggest that about 85% of HIV infections in South India occur through heterosexual transmission.5 Pregnant women are considered a proxy for the general population, and hence HIV prevalence among pregnant women is a key indicator of adult HIV prevalence.6

Karnataka has been one of the high-prevalent states in India, with the third-highest estimated PWH population of 269,470 and an incidence range of 0.01-0.05 per 1000 uninfected population. The adult HIV prevalence in Karnataka was 0.47% (0.37–0.59) in 2019, while the national average was 0.22% (0.17–0.29%) in 2019.4 On a positive note, Karnataka is the only state in India to achieve the targeted 75% reduction in new HIV infections between 2010 and 2019.4 HIV in Karnataka is heterogeneous and highly concentrated in specific regions and districts.7 Belgaum and Bangalore regions have consistently reported high HIV prevalence among antenatal clinic (ANC) attendees and the general population surveillance.7,8 India’s HIV Sentinel Surveillance (HSS) facilitates periodic monitoring of HIV prevalence at national and state levels. Besides HIV prevalence estimations, HSS serves as a preliminary indicator of sociodemographic factors associated with HIV risk. An analysis of recent HSS data reports a significant association of age, education, spouse occupation, and marital status with higher HIV prevalence among pregnant mothers and indicated that regions of high ANC-HIV prevalence were potentially those with high FSW-HIV prevalence.8 A previous study that analyzed the sociodemographic characteristics of HIV-positive pregnant women in Karnataka indicated that HIV was concentrated among pregnant women who were young and less educated, in their first gravida, residing in rural regions.9 While the levels and trends of HIV prevalence at the national and state level are available, probing further into the region and district-wise levels and trends of HIV prevalence will provide critical insights on district-level epidemic patterns for region-specific tailor-made interventions. Hence, this paper analyzes the HSS data of pregnant women to derive the district-wise levels and trends of HIV prevalence in Karnataka.

As one of the largest and robust surveillance systems, India’s HIV Sentinel Surveillance (HSS) facilitates periodic monitoring of HIV prevalence at national and state levels.10 Probing further into the region and district-wise levels and trends of HIV prevalence will provide critical insights on district-level epidemic patterns.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

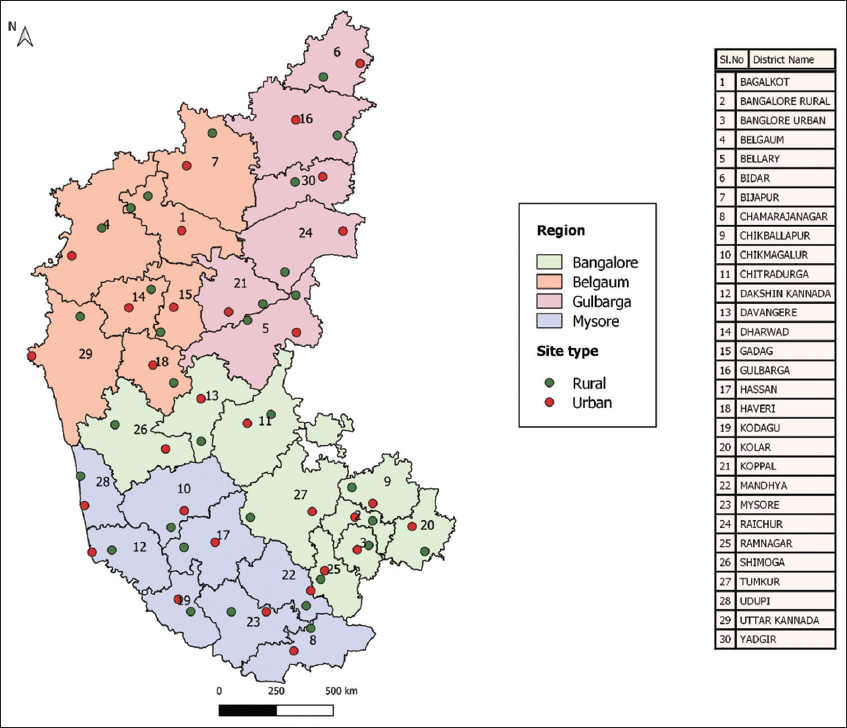

India’s HIV Sentinel Surveillance (HSS) is a cross-sectional survey conducted across 30 sentinel sites from urban and rural regions, comprising 60 sites in total, for the uniform representation of pregnant women (Figure 1). In this study, the HIV prevalence recorded at consistent sites in the last 11 rounds of HSS was considered to calculate the regional and district level HIV prevalence. Consistent sites were functional in at least four HSS rounds between 2003 and 2019 and were grouped into four regions: Bangalore, Belgaum, Gulbarga, and Mysore regions. The districts were grouped based on the four administrative divisions of Karnataka. All sites were functioning under a government healthcare facility.

- Distribution of HIV sentinel surveillance sites in Karnataka – 2019

Pregnant women aged 15-49 years and attending the ANC site for the first time during the surveillance period were included in the study. The sample size was 400 for each sentinel site.11,12 For each round of HSS, the study was conducted for three months or until the sample size was reached, whichever was earlier. In each site, participants were restricted to 20 per day to ensure data quality. A consecutive sampling method was followed to reduce sampling bias. The unlinked anonymous testing (UAT) strategy was followed until 2015 and was changed to the linked anonymous testing (LAT) strategy in 2017. Unlinked anonymous testing ensures the confidentiality of participants and minimizes participation bias. No personal identifiers are collected in this method, and a unique HSS code is assigned to the data forms and the test samples. However, to facilitate ART linkage and treatment management, the surveillance code is linked with the ANC registration number in a separate HSS register and maintained confidentially at the HSS sites.10 The standard two-test protocol was followed for HIV testing. The samples were tested through two ELISA or rapid tests or a combination of both at designated laboratories identified by NACO.11 The online data management software, Strategic Information Management System (SIMS), was used for data entry.13 The complete methodology of HSS and all standard operating procedures (SOP) were followed in all sites throughout the HSS as per the operational guidelines.10,11

2.2. Statistical Analysis

For each round of HSS, the state, regional, and district-level seroprevalence was calculated based on the formula, P = y/n, where ‘y’ denotes the number of HIV-positive pregnant women, and ‘n’ denotes the total number of pregnant women recruited. 95% CI (confidence interval) was calculated based on binomial and normal theory methods.14 Prevalence trends were identified by the Chi-square trend test, using the CDC software Epi Info 7.2. Then, the spatial variation of HIV prevalence through the years was analyzed using the QGIS software (version 3.83, 2019). For the last three HSS rounds (2015, 2017, 2019), HIV prevalence based on key sociodemographic variables was calculated. Districts reporting at least one HIV-positive case in two of the three rounds were identified against each sociodemographic variable to understand further the region-specific factors contributing to HIV positivity in each region.

2.3. Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. In HSS among pregnant women, HIV testing was anonymous, and the results were not used to determine the HIV status of a person. Hence, the written informed consent was waived, as endorsed in Item No. 6 under Chapter III, India HIV Act 2017.15 However, the pregnant mothers recruited for HSS were informed about the study purpose before data and sample collection.

3. Results

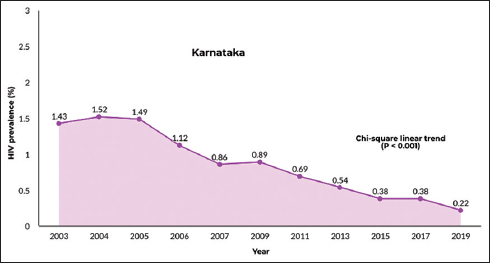

In total, 254,563 pregnant women were recruited for HSS from 2003 to 2019 in Karnataka. The state-, and regional trends and levels of HIV prevalence among pregnant women in Karnataka are represented in Table 1. The result indicates a significant decline (P<0.001) in HIV prevalence among pregnant women in Karnataka; 1.43 % (OR: 1.00 95% CI: 1.27 - 1.59) in 2003, to 0.69% (OR: 0.48 95%CI: 0.59 - 0.80) in 2011 and further to 0.22% (OR: 0.15 95% CI: 0.16 - 0.28) in 2019 (Figure 2).

| Year | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2009 | 2011 | 2013 | 2015 | 2017 | 2019 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Karnataka | ||||||||||||

| Tested | 21955 | 21534 | 21599 | 21627 | 21602 | 23192 | 23996 | 24767 | 24745 | 24800 | 24746 | < 0.001* |

| HIV Positive % | 1.43 | 1.52 | 1.49 | 1.12 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.69 | 0.54 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.22 | |

| (95% CI) | (1.27-1.59) | (1.36-1.68) | (1.33-1.65) | (0.98-1.26) | (0.74-0.98) | (0.77-1.01) | (0.59-0.80) | (0.45-0.63) | (0.31-0.46) | (0.30-0.46) | (0.16-0.28) | |

| OR | 1.00 | 1.06 | 1.04 | 0.78 | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.37 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.15 | |

| Bangalore | ||||||||||||

| Tested | 5998 | 5600 | 5599 | 5600 | 5600 | 7199 | 7197 | 7195 | 7200 | 7200 | 7183 | < 0.001* |

| HIV Positive % | 1.13 | 1.25 | 0.86 | 0.79 | 0.61 | 0.90 | 0.56 | 0.63 | 0.61 | 0.28 | 0.24 | |

| (95% CI) | (0.87-1.40) | (0.96-1.54) | (0.62-1.10) | (0.55-1.02) | (0.40-0.81) | (0.68-1.12) | (0.38-0.73) | (0.44-0.81) | (0.43-0.79) | (0.16-0.40) | (0.12-0.35) | |

| OR | 1 | 1.1 | 0.75 | 0.69 | 0.53 | 0.79 | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.24 | 0.21 | |

| Belgaum | ||||||||||||

| Tested | 5579 | 5600 | 5600 | 5627 | 5600 | 5599 | 5599 | 5988 | 6000 | 6000 | 5981 | < 0.001* |

| HIV Positive % | 2.15 | 2.04 | 2.52 | 1.46 | 0.75 | 1.07 | 1.18 | 0.40 | 0.28 | 0.53 | 0.32 | |

| (95% CI) | (1.77-2.53) | (1.67-2.41) | (2.11-2.93) | (1.14-1.77) | (0.52-0.98) | (0.80-1.34) | (0.90-1.46) | (0.24-0.56) | (0.15-0.42) | (0.35-0.72) | (0.18-0.46) | |

| OR | 1 | 0.95 | 1.18 | 0.67 | 0.34 | 0.49 | 0.54 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.24 | 0.14 | |

| Gulbarga | ||||||||||||

| Tested | 3988 | 4000 | 4000 | 4000 | 4002 | 3998 | 4800 | 5191 | 5200 | 5200 | 5191 | < 0.001* |

| HIV Positive % | 2.08 | 1.68 | 1.78 | 1.23 | 1.20 | 0.60 | 0.58 | 0.42 | 0.25 | 0.44 | 0.17 | |

| (95% CI) | (1.64-2.52) | (1.28-2.07) | (1.37-2.18) | (0.88-1.57) | (0.86-1.54) | (0.36-0.84) | (0.37-0.80) | (0.25-0.60) | (0.11-0.39) | (0.26-0.62) | (0.06-0.29) | |

| OR | 1.00 | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.58 | 0.57 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.08 | |

| Mysore | ||||||||||||

| Tested | 6390 | 6334 | 6400 | 6400 | 6400 | 6396 | 6400 | 6393 | 6345 | 6400 | 6391 | < 0.001* |

| HIV Positive % | 0.67 | 1.20 | 0.97 | 1.06 | 0.97 | 0.89 | 0.50 | 0.66 | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.14 | |

| (95% CI) | (0.47-0.87) | (0.93-1.47) | (0.73-1.21) | (0.81-1.31) | (0.73-1.21) | (0.66-1.12) | (0.33-0.67) | (0.46-0.86) | (0.19-0.47) | (0.16-0.43) | (0.05-0.23) | |

| OR | 1 | 1.79 | 1.44 | 1.59 | 1.44 | 1.33 | 0.74 | 0.98 | 0.49 | 0.44 | 0.21 | |

- Trend of HIV prevalence (%) among pregnant women attending ANC clinics in Karnataka (2003 -2019)

- Figure shows yearly surveillance until 2007 and biennial surveillance henceforth.

3.1. HIV Prevalence at the Regional Level

In all four regions of Karnataka, the HIV prevalence trend indicated a significant decline (P<0.001) as presented in Table 1. In Bangalore region, the prevalence declined from 1.13 % (95% CI: 0.87% - 1.40%) in 2003 to 0.24% (95% CI: 0.12 – 0.35) in 2019: in Belgaum region from 2.15% (95% CI: 1.77% - 2.53%) to 0.32 % (95% CI: 0.18 % - 0.46 %); in Gulbarga region from 2.08 % (95% CI: 1.64% - 2.52 %) to 0.17 % (95% CI: 0.06 % - 0.29 %), and in Mysore region from 0.67 % (95% CI: 0.47 %- 0.87 %) to 0.14% (95% CI: 0.05% - 0.23%).

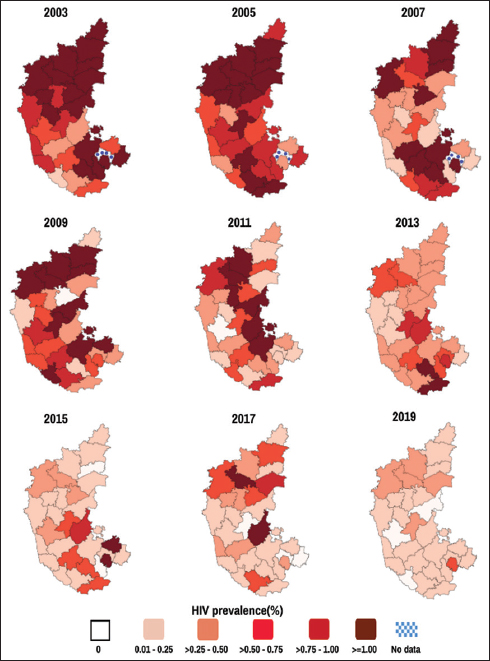

3.2. HIV Prevalence at the District Level

Most districts in Karnataka indicated a significant decline in HIV prevalence but had inter-district variations. Spatial variation of the HIV prevalence in the districts of Karnataka (Table 2) is shown in Figure 3. Significant decline (P<0.05) was observed in 26 districts in Belgaum, Gulbarga and Mysore regions. Four districts (Bangalore Urban, Bangalore Rural, Chikballapur and Chitradurga) recorded a declining trend, which, however, was not statistically significant (P>0.05). Bangalore, Davangere, Tumkur, Bagalkot, Belgaum, Bijapur, Chamrajnagar, and Hassan recorded a prevalence of 0.5 and above in at least 8 of the 11 HSS.

| Region | District | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2009 | 2011 | 2013 | 2015 | 2017 | 2019 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangalore | Bangalore Urban | 1.17 | 0.63 | 0.50 | 1.38 | 1.25 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.88 | 1.13 | 0.50 | 0.63 | 0.223 |

| Bangalore | Bangalore Rural | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.38 | 0.13 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.348 |

| Bangalore | Chikballapur | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 1.25 | 0.38 | 0.50 | 1.75 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.957 |

| Bangalore | Chitradurga | 0.38 | 0.75 | 0.63 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 1.25 | 0.88 | 1.00 | 1.13 | 0.13 | 0.221 |

| Bangalore | Davangere | 0.88 | 2.13 | 1.38 | 1.38 | 0.75 | 2.00 | 0.75 | 0.88 | 0.63 | 0.00 | 0.50 | <0.001* |

| Bangalore | Kolar | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.00 | 1.50 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.13 | <0.001* |

| Bangalore | Ramnagaram | 1.88 | 2.50 | 0.88 | 0.50 | 0.13 | 0.63 | 0.50 | 0.75 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.13 | <0.001* |

| Bangalore | Shimoga | 0.75 | 0.50 | 0.88 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.38 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.001* |

| Bangalore | Tumkur | 1.88 | 1.50 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 1.13 | 1.13 | 1.50 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | <0.001* |

| Belgaum | Bagalkot | 2.75 | 2.63 | 2.88 | 2.13 | 0.63 | 2.13 | 3.50 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 1.17 | 0.42 | <0.001* |

| Belgaum | Belgaum | 4.43 | 4.25 | 3.63 | 3.13 | 2.00 | 1.50 | 0.88 | 0.75 | 0.50 | 0.63 | 0.50 | <0.001* |

| Belgaum | Bijapur | 1.63 | 1.38 | 2.13 | 1.23 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 1.75 | 0.50 | 0.13 | 0.38 | 0.50 | <0.001* |

| Belgaum | Dharwad | 3.00 | 2.88 | 6.75 | 0.88 | 0.38 | 0.63 | 0.50 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.38 | 0.25 | <0.001* |

| Belgaum | Gadag | 0.88 | 1.13 | 1.13 | 0.88 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 1.13 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.38 | 0.13 | <0.001* |

| Belgaum | Haveri | 1.39 | 0.63 | 0.38 | 0.63 | 0.25 | 0.63 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.25 | <0.001* |

| Belgaum | Uttara Kannada | 1.00 | 1.38 | 0.75 | 1.35 | 0.50 | 0.13 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.13 | <0.001* |

| Gulbarga | Bellary | 1.63 | 1.13 | 0.88 | 1.38 | 0.38 | 1.13 | 1.25 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.00 | <0.001* |

| Gulbarga | Bidar | 1.39 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 1.13 | 0.13 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.13 | <0.001* |

| Gulbarga | Gulbarga@ | 1.63 | 2.25 | 2.63 | 0.88 | 2.74 | 1.25 | 0.25 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0.25 | <0.001* |

| Gulbarga | Koppal | 4.13 | 3.00 | 2.88 | 1.63 | 1.25 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.38 | 0.50 | 0.63 | 0.13 | <0.001* |

| Gulbarga | Raichur | 1.63 | 1.13 | 1.63 | 1.38 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.88 | 0.38 | <0.001* |

| Gulbarga | Yadgir^ | 1.63 | 2.25 | 2.63 | 0.88 | 2.74 | 1.25 | 0.63 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.25 | <0.001* |

| Mysore | Chamrajnagar | 0.51 | 1.00 | 1.63 | 1.38 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.88 | 1.25 | 0.63 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.012* |

| Mysore | Chikmagalur | 0.50 | 0.95 | 0.88 | 1.50 | 2.38 | 0.75 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.38 | 0.13 | <0.001* |

| Mysore | Dakshina Kannada | 0.88 | 1.38 | 0.38 | 0.75 | 0.13 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | <0.001* |

| Mysore | Hassan | 0.75 | 1.00 | 1.38 | 2.38 | 1.25 | 0.88 | 0.75 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.13 | 0.13 | <0.001* |

| Mysore | Kodagu | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.50 | 0.75 | 2.63 | 0.63 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.025* |

| Mysore | Mandya | 1.13 | 1.13 | 1.00 | 0.25 | 1.25 | 0.13 | 0.50 | 1.13 | 0.54 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.002* |

| Mysore | Mysore | 0.50 | 2.38 | 1.13 | 1.00 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.13 | 0.50 | 0.13 | 0.63 | 0.13 | <0.001* |

| Mysore | Udupi | 0.88 | 1.00 | 0.63 | 0.75 | 0.13 | 0.63 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 0.13 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.015* |

- Geographical variation of HIV Prevalence (%) among pregnant women across the districts in Karnataka (2003-2019)

4. Discussion

Karnataka has been among India’s high HIV prevalence states, with a prevalence of 1.43% among pregnant women in 2003. The prevalence significantly decreased (P<0.001) to 0.38% in 2019, which was still higher than the national average of 0.28%.4 In the general population, HIV prevalence of ≥1% indicates a high prevalence, 0.5-0.99 indicates moderate prevalence, and prevalence < 0.5 indicates a low prevalence.16 In 2003, Karnataka recorded high HIV prevalence among pregnant women in 18 districts, moderate prevalence in 10 and low prevalence in 2 of its 30 districts. In 2019, the state recorded moderate prevalence in 4 districts and low prevalence in all the remaining districts (Table 2). The trend significantly declined or stabilized in most districts since 2011, while it was fluctuating in Chikballapur and Chitradurga districts in the Bangalore region. (Table 2).

Karnataka’s first HIV case was reported in 1988 in Belgaum.17 The National AIDS Control Organization (NACO), Karnataka State AIDS Prevention Society (KSAPS), the District AIDS Control and Prevention units (DAPCUs), and private partners implemented and monitored various HIV interventions in Karnataka. From 2003, a consistent decline in HIV prevalence among pregnant women was predominantly observed in Karnataka, owing to various interventions. Reports show that a higher prevalence among the high–risk groups (HRGs) reflects on the HIV prevalence of pregnant women.18 Hence the early stages of the interventions were predominantly focused on HRGs, and had a measurable impact on HIV prevention in the general population.19 Some of the notable interventions that had a potential impact on HRG behavior and HIV prevalence and the subsequent impact on ANC prevalence are discussed here.

Initially, India-Canada Collaborative HIV/AIDS Project (ICHAP) was implemented in collaboration between the University of Manitoba and KSAPS to carry out HIV prevention and control programs in rural Karnataka in 2001.20 The Karnataka Health Promotion Trust (KHPT) was formed in 2003 as a collaborative partnership between the University of Manitoba and KSAPS to deliver HIV/AIDS services in Karnataka.21,22 KHPT implemented and supported various initiatives such as Sankalp, Corridors and Samastha for HIV prevention and management.22 In 2003, Avahan, an India AIDS Initiative that aimed to scale up the HIV prevention services, was implemented in six high-prevalent states in India. As a part of the Avahan initiative, the ‘Sankalp’ was launched in 18 districts in Karnataka for HIV prevention services to HRGs and the bridge population.22 In 2005, ‘Corridors’ was launched in Northern Karnataka for HIV services among HRGs who live and migrate across the border districts of North Karnataka and South Maharashtra.23 During 2006-2011, the Samastha project was implemented in 13 high-prevalence districts in Karnataka.23 It was an enhanced care model and used a district-based approach to strengthen and coordinate the existing HIV healthcare services.24,25 Implementation of behavioral interventions and advocacy for safer sex was the primary idea of Avahan initiatives. The prevention services included commodity distribution (free condoms, needles and syringes), extensive peer-outreach, community mobilization, dedicated health services to FSWs and their clients, creating an enabling environment and other psychological support programs.21 Further, in 2004, antiretroviral therapy (ART) was initiated in Karnataka, which subsequently increased the ART enrollment.26

Avahan scaled up the prevention services during Phase I (2003-2008) and transitioned the services to NACO in Phase II (2008-2013).27 A series of assessments conducted between 2004-2012 at selected districts in Karnataka showed that the prevalence of HIV and STI declined considerably and reported significantly high rates of condom usage with regular clients.28,29 A modeling study indicates that under certain conditions in a concentrated epidemic, a significant decline in ANC prevalence is achievable through effective interventions among FSW.30 The study also reports evidence of localized interventions in certain districts of Karnataka even before 2003.30 The overall declining trend in the HIV prevalence among pregnant women since 2011 is most likely a synergized impact of the interventions implemented in Karnataka. Nevertheless, the recent years’ prevalence trends reached stabilization and require targeted measures to achieve the global agenda of ‘Eliminating AIDS by 2030’.

To understand the recent trends, HIV prevalence and the districts with a minimum of one HIV-positive pregnant woman in the last three rounds of HSS (2015, 2017, 2019) were categorized under key sociodemographic factors often associated with infection risk (Table 3). Based on this disaggregated data, the prevalence was higher among pregnant women aged 25-49 years, illiterates, residing in rural regions and those whose spouse was laborers or transport workers. HIV positivity in recent HSS rounds was constantly reported in districts of Bangalore, Chikballapur, Chitradurga, Davanagere, Tumkur, Bagalkot, Belgaum, Bijapur, Gadag, Dharwad, Gulbarga, Bellary, Koppal, Raichur, Chikmagalur, Hassan and Mysore. Belgaum region, known for the traditional sex trade,31 consistently recorded the highest HIV prevalence. In our analysis, Belgaum had a prevalence of 0.5 and above in all HSS since 2003, the highest being 4.43 in 2003 (Table 2). Bangalore Urban and Davangere districts in the Bangalore region also recorded a higher prevalence. Previous studies show that HIV among pregnant women in Karnataka is highly concentrated in the northern (Belgaum region) and southern districts (Bangalore region), particularly those with high HIV prevalence among HRGs.7,8 While spouse occupation being laborers, seasonal migration and commercial sex trade were associated with infection risks in North Karnataka, spouse occupation being truckers and transport workers were associated with infection risks in South Karnataka.8,9 It is noteworthy that although no significant variation was observed in the overall urban-rural prevalence in Karnataka, HIV positivity in the recent rounds was comparatively higher in the rural areas (Table 3). In 2019, HIV prevalence in the rural sites ranged between 0.00% - 2.13%, and the rural sites in Bangalore Rural (2.13%), Bijapur (0.77%), Belgaum (0.68%), Raichur (0.63%) Bagalkot (0.62%) and Davanagare (0.57%) recorded higher prevalence. HIV prevalence in the urban sites ranged between 0.00% - 0.53%, with the highest prevalence in Bangalore Urban (0.53%).32 Further disaggregated analysis of the region-specific factors associated with infection risk may indicate the regional variations, the rising pockets of infection and the possibilities of intervention optimizations.

| Sociodemographic Variables | HIV Prevalence (%) | Districts reporting at least one HIV positive pregnant mother in any 2 of the last 3 HSS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2017 | 2019 | Regions | ||||

| Bangalore | Belgaum | Gulbarga | Mysore | ||||

| Age (Yrs.) | |||||||

| 15-24 | 0.28 | 0.33 | 0.19 | Bangalore Urban, Chikballapur, Chitradurga, Davanagere, Kolar, Ramanagaram, Tumkur | Bagalkot, Belgaum, Bijapur, Gadag, Dharwad, Haveri, Uttara Kannada | Bellary, Gulbarga, Koppal, Yadgir | Chamrajnagar, Chikmagalur, Hassan, Kodagu, Mandya, Mysore |

| 25-49 | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.25 | Bangalore Urban, Bangalore Rural, Chitradurga, Davanagere, Tumkur | Bagalkot, Belgaum, Bijapur, Dharwad, Gadag, Uttara Kannada | Bellary, Bidar, Gulbarga, Koppal, Raichur | Chamrajnagar, Chikmagalur, Dakshina Kannada, Hassan, Udupi, Kodagu, Mandya, Mysore |

| Education | |||||||

| Illiterate | 0.60 | 0.46 | 0.45 | Chikballapur, Tumkur | Bagalkot, Belgaum | Bellary, Koppal, Raichur, Yadgir | - |

| Literate & till 5th standard | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.29 | Chitradurga, Davanagere | Bagalkot | - | Hassan, Udupi |

| 6th to 10th standard | 0.38 | 0.33 | 0.22 | Bangalore Urban, Bangalore Rural, Chikballapur, Chitradurga, Davanagere, Ramanagaram, Tumkur | Bagalkot, Belgaum, Bijapur, Gadag, Haveri, Dharwad, Uttara Kannada | Gulbarga, Koppal | Chamrajnagar, Mandya, Mysore, Chikmagalur, Dakshina Kannada, Hassan, Kodagu |

| 11th to Graduation | 0.16 | 0.43 | 0.14 | Chitradurga | Bagalkot, Belgaum, Bijapur, Uttara Kannada | - | Chikmagalur, Udupi |

| Post-Graduation | 0.43 | 0.47 | 0.14 | - | - | - | - |

| Gravida Status | |||||||

| First | 0.33 | 0.43 | 0.24 | Bangalore Urban, Chikballapur, Chitradurga, Davanagere, Shimoga | Bagalkot, Belgaum, Bijapur, Gadag, Haveri, Uttara Kannada | Bidar, Gulbarga, Koppal, Raichur | Chamrajnagar, Chikmagalur, Hassan, Udupi |

| Second | 0.45 | 0.32 | 0.19 | Bangalore Urban, Bangalore Rural, Chitradurga, Davanagere, Tumkur | Bagalkot, Belgaum, Bijapur, Gadag, Uttara Kannada | Gulbarga, Koppal, Raichur | Mandya, Mysore, Chamrajnagar, Chikmagalur, Dakshina Kannada, Hassan, Udupi |

| Third | 0.28 | 0.36 | 0.23 | Bagalkot, Belgaum, Dharwad | Gulbarga | Kodagu | |

| Fourth/More | 0.26 | 0.43 | 0.20 | - | - | - | - |

| Spouse Occupation | |||||||

| Agricultural Laborer | 0.46 | 0.31 | 0.22 | Chikballapur | Bagalkot, Gadag | Koppal, Raichur | Chikmagalur, Hassan, Kodagu |

| Non-Agricultural Laborer@ | 0.23 | 0.39 | 0.24 | Bangalore Urban, Bangalore Rural, Chitradurga, Kolar, Ramanagaram, Tumkur | Bagalkot, Belgaum, Dharwad, Uttara Kannada | Bellary | Chamrajnagar, Hassan, Mandya |

| Skilled/Semiskilled worker# | 0.35 | 0.17 | 0.15 | Bangalore Urban | Belgaum | Raichur | Dakshina Kannada |

| Truck Driver/helper | 1.16 | 0.91 | 0.00 | Bangalore Urban | - | - | - |

| Local transport worker$ | 0.43 | 0.62 | 0.22 | Davanagere | Bagalkot, Bijapur | Bidar, Koppal | Mysore |

| Current residence | |||||||

| Urban | 0.30 | 0.36 | 0.15 | Bangalore Urban, Bangalore Rural, Chikballapur, Chitradurga, Davanagere | Bagalkot, Bijapur, Dharwad, Gadag, Haveri, Uttara Kannada | Bellary, Bidar, Gulbarga, Koppal | Mandya, Mysore |

| Rural | 0.41 | 0.38 | 0.26 | Chikballapur, Chitradurga, Davanagere, Shimoga, Tumkur | Bagalkot, Belgaum, Bijapur, Dharwad, Gadag, Haveri, Uttara Kannada | Bellary, Gulbarga, Koppal, Raichur, Yadgir | Chikmagalur, Dakshina Kannada, Hassan, Udupi, Kodagu, Mysore |

The study provides preliminary evidence of regional and district–level HIV prevalence trends in Karnataka and gives insights to focus areas for prevention services among pregnant women. Alongside prevention services, HIV treatment and management play a significant role in ensuring the prevention of neonatal transmission. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) and prevention of parent to child transmission (PPTCT) programs are being implemented at the national and state levels.33 Universal HIV testing, early access and adherence to ART, follow-up and periodic viral load assessments are essential to prevent neonatal HIV transmission, for which awareness on HIV management is essential.34 As per the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) data, about 24.5% of females aged between 15 - 49 years in Karnataka had a comprehensive knowledge of HIV in 2020, while it was 9.5% in 2016.35 Counseling and integration of HIV treatment services with antenatal care are shown to positively impact voluntary HIV testing and ART adherence, whereas follow-up was a major barrier in PPTCT services.34,36 A recent meta-analysis on community-based HIV initiatives that effectively achieved UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets shows that various strategies include deployment of community workers/peers, combined test and treat strategies, educational methods, mobile testing, campaigns and technology. The results suggested that the deployment of community healthcare workers/peer workers significantly improved viral suppression and encouraged innovative interventions for HIV management.37 Reports on the efficiency of innovative methods such as digital platforms, distribution of self-test kits that encourage voluntary testing and subsequent ART linkage among pregnant mothers are emerging. 38,39 The feasibility and accessibility of such novel strategies will fastrack further decline in HIV prevalence among pregnant women in Karnataka.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations of the study

HSS is a cross-sectional survey which is having its limitation in predicting the temporal relationship. HSS in Karnataka predominantly included pregnant women attending the government ANC. Hence, this analysis does not consider the HIV prevalence of those attending private ANC. The paper is limited to trend analysis and does not analyze the structural and behavioral factors associated with infection trends because such contextual data for pregnant women is scarce.

5. Conclusion and Global Health Implications

The current analysis indicates a significant decrease in almost all districts in Karnataka since 2003. However, inter-district variations were observed, with the prevalence reaching stabilizing levels in the last few years. Our findings will be instrumental in facilitating targeted interventions at regions of high prevalence.

The global agenda of ‘End of AIDS by 2030’ necessitates regionalized and disaggregated analysis at sub-national levels. Such an approach will help identify the emerging pockets of new HIV infections, zones of concentrated epidemic and contextual factors driving the disease transmission. This paper identifies regions of a concentrated epidemic, with further scope to identify and intervene on the underlying region-specific factors affecting disease transmission.

Acknowledgments:

The authors wish to thank the National AIDS Control Organization, Karnataka State AIDS Control Society, National and State Reference Laboratories, State Surveillance Team members, District AIDS Prevention Control Units, and sentinel site personnel for their support in completing the surveillance activities on time. The authors also express their gratitude to Dr. Sanjay Mehendale, former Additional Director General, Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, and Dr. Manoj V Murhekar, Director, ICMR-National Institute of Epidemiology, Chennai, for their support and technical inputs towards conducting the surveillance.

Compliance With Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no competing interests.

Financial Disclosure: Nothing to declare.

Funding/Support: Funding was received from the National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) (Government of India) for conducting the HIV Sentinel Surveillance (HSS) in the states, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Kerala, Odisha, Puducherry, and Tamil Nadu. NACO Grant No. T-11020/02/2015-NACO (Surveillance).

Disclaimer: None

References

- HIV/AIDS:Key Facts. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids Published July 17, 2021

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. http://naco.gov.in/hiv-facts-figures

- Modelling and estimation of HIV prevalence and number of people living with HIV in India, 2010–2011. Int J STD AIDS. 2016;27(14):1257-1266. doi:10.1177/0956462415612650

- [Google Scholar]

- 2020. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. http://naco.gov. in/sites/default/files/INDIA%20HIV%20ESTIMATES.pdf

- AIDS in South Asia:Understanding and Responding to a Heterogenous Epidemic. Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2006. p. :7-19.

- HIV surveillance among pregnant women attending antenatal clinics:evolution and current direction. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2017;3(4):e85. doi:10.2196/publichealth.8000

- [Google Scholar]

- Heterogeneity of the HIV epidemic in the general population of Karnataka state, south India. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(Suppl 6(Suppl 6)):S13. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-S6-S13

- [Google Scholar]

- Heterogeneity and confinement of HIV prevalence among pregnant women calls for decentralized HIV interventions:Analysis of data from three rounds of HIV sentinel surveillance in Karnataka:2013–2017. Indian J Community Med. 2021;46(1):121-125. doi:10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_68_20

- [Google Scholar]

- Confined vulnerability of HIV infection among pregnant women attending antenatal care clinics in Karnataka, India:Analysis of data from the HIV sentinel surveillance 2017. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2020;8(4):1127-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. http://naco.gov.in/sites/ default/files/ANC%20HSS%202017%20Operational%20 manual.pdf

- Annual HIV Sentinel Surveillance - Country Report 2008-2009. http://naco.gov.in/sites/default/files/HIV%20Sentinel%20Surveillance%20India%20Country%20Report%2C%202008-09.pdf Published 2011

- Guidelines For Conducting Hiv Sentinel Serosurveys Among Pregnant Women And Other Groups. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/surveillance/en/ancguidelines.pdfPublished 2003

- Strategic Information Management System. http://www.naco. gov.in/strategic-information-management. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India

- Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion:comparison of seven methods. Stat Med. 1998;17(8):857-72. doi:10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980430)17:8<857::aid-sim777>3.0.co;2-e

- [Google Scholar]

- The Gazette of India. http://naco.gov.in/sites/default/files/HIV%20AIDS%20Act. pdf. Published April 21, 2017

- Prioritization Of Districts For Programme Implementation. http://naco.gov.in/sites/default/files/District%20Categorisation%20for%20Priority%20Attention.pdf

- Socio-Economic Impact of HIV and AIDS in India. 2006. United Nations Development Program. http://www.undp.org/content/dam/india/docs/socio_eco_impact_hiv_aids_%20india.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Ecological analysis of the association between high-risk population parameters and HIV prevalence among pregnant women enrolled in sentinel surveillance in four southern India states. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86(Suppl 1(Suppl_1)):i10-6. doi:10.1136/sti.2009.038323

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of an intensive HIV prevention programme for female sex workers on HIV prevalence among antenatal clinic attenders in Karnataka state, south India:an ecological analysis. AIDS. 2008;22(Suppl 5):S101-8. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000343768.85325.92

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and determinants of HIV infection in South India:a heterogeneous, rural epidemic. AIDS. 2007;21(6):739-47. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e328012b885

- [Google Scholar]

- An integrated structural intervention to reduce vulnerability to HIV and sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers in Karnataka state, south India. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:755. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-755

- [Google Scholar]

- 2013. Annual Report 2011- 2012. Bangalore: Karnataka Health Promotion Trust; https://www. khpt.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/KHPT-Annual- Report-2011-12.pdf

- Factors affecting quality of life of people living with HIV In Karnataka, India. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87:A340-A341.

- [Google Scholar]

- A Positive Partnership:Integrating HIV and Tuberculosis Services in Karnataka, India. In: Case Study Series. Arlington, VA: USAID's AIDS Support and Technical Assistance Resources, AIDSTAR-One, Task Order 1; 2012.

- [Google Scholar]

- Scaling up antiretroviral treatment services in Karnataka, India:impact on CD4 counts of HIV-infected people. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e72188. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0072188

- [Google Scholar]

- CHARME–1 Evaluation Group. The costs of scaling up HIV prevention for high-risk groups:lessons learned from the Avahan Programme in India. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e106582. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0106582

- [Google Scholar]

- Changes in HIV and syphilis prevalence among female sex workers from three serial cross-sectional surveys in Karnataka state, South India. BMJ Open. 2015;5(3):e007106. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007106

- [Google Scholar]

- Changes in risk behaviours and prevalence of sexually transmitted infections following HIV preventive interventions among female sex workers in five districts in Karnataka state, south India. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86(Suppl 1(Suppl_1)):i17-24. doi:10.1136/sti.2009.038513

- [Google Scholar]

- Using mathematical modelling to investigate the plausibility of attributing observed antenatal clinic declines to a female sex worker intervention in Karnataka state, India. AIDS. 2008;22:S149-64. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000343773.59776.5b

- [Google Scholar]

- Girl, woman, lover, mother:Towards a new understanding of child prostitution among young Devadasis in rural Karnataka, India. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007;64(12):2379-90. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.031

- [Google Scholar]

- 2020. Indian Council of Medical Research, Dept. of Health Research, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. https://www.nie.gov.in/images/ reports/pdf/Karnataka_2019.pdf

- 2016. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. http://naco.gov. in/sites/default/files/NACO%20ANNUAL%20REPORT%20 2016-17.pdf

- Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission:a mathematical model. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):48-57. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61697-9

- [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. http://rchiips.org/NFHS/NFHS-5_FCTS/NFHS-5%20State%20Factsheet%20Compendium_Phase-I.pdf

- Uptake of PPTCT services among HIV sero-positive pregnant women in Mumbai, India-A descriptive study. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2021;11:100775.

- [Google Scholar]

- Which community-based HIV initiatives are effective in achieving UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets?A systematic review and meta-analysis of evidence (2007-2018) PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0219826. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0219826

- [Google Scholar]

- Will an innovative connected AideSmart!app-based multiplex, point-of-care screening strategy for HIV and related coinfections affect timely quality antenatal screening of rural Indian women?Results from a cross-sectional study in India. Sex Transm Infect. 2019;95(2):133-139. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2017-053491

- [Google Scholar]

- Feasibility of supervised self-testing using an oral fluid-based HIV rapid testing method:a cross-sectional, mixed method study among pregnant women in rural India. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(1):20993. doi:10.7448/IAS.19.1.20993

- [Google Scholar]