Translate this page into:

Complementary Feeding Knowledge, Practices, and Dietary Diversity among Mothers of Under-Five Children in an Urban Community in Lagos State, Nigeria

*Corresponding author email: folaton@gmail.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Inappropriate complementary feeding is a major cause of child malnutrition and death. This study determined the complementary feeding knowledge, practices, minimum dietary diversity, and acceptable diet among mothers of under-five children in an urban Local Government Area of Lagos State, Southwest Nigeria.

Methods:

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted in Eti-Osa area of Lagos State, Nigeria. Multi-stage sampling technique was employed to select 355 mothers and infants. Data was collected using a pre-tested interviewer administered questionnaire and 24-hour diet recall was used to assess dietary diversity. Data was analyzed using Epi-Info.

Results:

Knowledge of complementary feeding was low (14.9%) and was associated with older mothers’ age, being married, and higher level of education. The prevalence of timely initiation of complementary feeding (47.9%), dietary diversity (16.0%) and minimum acceptable diet for children between 6 and 9 months (16%) were low. Overall, appropriate complementary feeding practice was low (47.0%) and associated with higher level of mothers’ education and occupation.

Conclusions and Global Health Implications:

Complementary feeding knowledge and practices were poor among mothers of under-5 especially the non-literate. Reduction of child malnutrition through appropriate complementary feeding remains an important global health goal. Complementary feeding education targeting behavioral change especially among young, single and uneducated mothers in developing countries is important to reduce child morbidity and mortality.

Keywords

Complementary Feeding

Infant Feeding

Infant and Child Health

Mothers of Under-five Children

Pediatrics

1. Background and Introduction

The requirements of the infant for energy and nutrients start to exceed what is provided by breast milk at the age of 6 months and complementary foods are necessary to meet those needs. Complementary foods are often of inadequate nutritional quality, or they are given too early or too late, in too small amounts, or not frequently enough. If the feeds are given inappropriately, the growth of the infant may falter.[1] In many developing countries, the incidence of under-nutrition usually increases during the period of complementary feeding from the age of 6 to 18 months.[2] The occurrence of early nutritional deficits is linked to long-term impairments in child growth and health.[3]

In Nigeria, according to the 2013 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), the national prevalence of appropriate complementary feeding practices among children aged 6-23 months was 10%, while in States such as Lagos, Akwa-Ibom, Imo, Zamfara and Benue, the prevalence rates of appropriate complementary feeding practices were only 3.2%, 8.1%, 9.3%, 1% and 12.4% respectively.[4] More than 50% of infants are given complementary food too early which is usually of poor nutritional value.[4] In many countries including Nigeria, less than a fourth of infants within the age 6–23 months meet the criteria of dietary diversity and feeding frequency that are appropriate for their age. Thus, only few children receive nutritionally adequate and safe complementary food.[1]

Inappropriate complementary feeding practice may result in malnutrition and cause various diseases. Almost half (45%) of all children’s deaths are associated with malnutrition, while children in sub-Saharan Africa are more than 14 times likely to die before the age of 5 than children in developed regions.[5] Malnutrition has been the underlying factor leading to childhood killer diseases such as malaria, pneumonia, diarrhea. Under-nutrition causes stunting, underweight and wasting. In Nigeria, the 2013 DHS reported that the proportion of children under 5 years who were stunted, underweight and wasted was 37%, 29% and 18% respectively.[4]

Malnutrition can also lead to obesity in adulthood which is a risk factor for many diet related non-communicable diseases such as hypertension, heart diseases, diabetes and some types cancer.[6] Child malnutrition hurts cognitive function and contributes to poverty by impeding a child’s ability to lead productive lives, hence slows down national development. Thus, adequate and timely complementary feeding practices do not only regulate growth and functional development of a young child, but also appear to play a pivotal role in lifelong programming effects that regulate health, disease, mortality risks, neural function and behavior, and quality of life in adulthood.[7]

Until now, indicators used to measure infant and young child feeding practices in population-based surveys have focused mostly on breastfeeding practices.[8] Considerations were not given to quantity and quality of complementary foods including dietary diversity like breast feeding. Meanwhile, inadequate knowledge about appropriate foods and the prevalent feeding practices are often greater determinants of malnutrition than the lack of food.[9] Having good complementary feeding knowledge and practices among mothers of under-five children will prevent the consequences of under-nutrition thereby enabling children to receive appropriate nutrition and consequently achieve their full human potential.

Previous studies on complementary feeding show low level of complementary feeding knowledge and appropriate practices. In South India, only 8% of mothers had proper knowledge of all aspects of complementary feeding.[9] In Southern Ethiopia, timely initiation of complementary feeding, minimum meal frequency and minimum dietary diversity were 72.5, 67.3 and 18.8% among mothers of children aged 6–23 months respectively. Only 9.5% of mothers practiced appropriate complementary feeding.[10] In Ghana, only 13% of children aged 6-23months met the minimum standards of the infant and young child feeding practices (IYCF).[11] Between 2003 and 2013, in Nigeria, there was a decreasing prevalence (from 2003 to 2013) of timely introduction of complementary foods (67% to 57%); minimum dietary diversity (33% to 24%) and minimum acceptable diet (13% to 8%) among mothers who were educated.[12]

State or local health information can be a powerful vehicle for improving the health of a community, guiding local action in support of policy changes, and improving programs’ effectiveness.[13] A study conducted in Enugu State, Nigeria revealed that 68.7% of the respondents had good knowledge towards infant feeding while the eventual practice of the mothers revealed that only 22.4% had adequate practice of infant feeding; however, in this study, knowledge and practice of complementary feeding were not separately assessed.[14] In previous study in Lagos State, the prevalence of timely introduction of complementary foods was 45% and minimum frequency of meals appropriate for age was attained by only 37.3% of the children.[15] However, the previous study did not determine the complementary feeding knowledge, summary of complementary feeding practices, minimum dietary diversity and acceptable diet among the children aged 6-23 months in Lagos State.

Consequently, despite its potential, little is known about the complementary feeding knowledge and practices especially minimum dietary diversity, and acceptable diet among mothers of under-five in Lagos State. Eti-Osa Local Government Area (LGA) is one of the 20 urban LGAs in Lagos State and no known study has been conducted on complementary feeding knowledge, practices and dietary diversity in the area. The purpose of this study was therefore to determine complementary feeding knowledge, practices, minimum dietary diversity and acceptable diet amongst mothers of under-five children in Eti-Osa Local Government Area (LGA) of Lagos State.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study design

The study was conducted among mothers of under-five children in Eti-Osa local government area of Lagos State. Eti-Osa is one of the 20 Local Government Areas in Lagos state having a total populace of 287,785 as recorded by the last census conducted in 2006. The design was cross sectional and descriptive. The minimum sampling size calculated using national prevalence of appropriate complementary feeding practice (30%)[16] was 323; however, a multistage sampling method was used to select three hundred and fifty five (355) mothers to make provisions for non-response. Four wards were selected from the LGA using simple random sampling technique by balloting. Five streets were chosen from each of the four wards using balloting technique, to obtain twenty streets and all the houses with an eligible woman or mother on each street were included. In the houses where there was more than one eligible woman, simple random sampling technique by balloting was used to select a participant. A mother and child were included in the study if the youngest child was at least one year and less than 5 years of age. The youngest child was taken as the index child and all the responses obtained were based on this child.

2.2. Study variables

The independent variables include the socio-demographic characteristics of the children such as age and sex of index child. The dependent variables for this study were complementary feeding knowledge, complementary feeding practices (including meal frequency), dietary diversity, and minimum acceptable diet. Our study covariates include maternal age, marital status, level of education, occupation and no of children.

Definition of variables were based on the definitions of the variables according to the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines.[17] Minimum feeding frequency was defined as proportion of breastfed and non-breastfed children, 6-23.9 months of age who receive solid, semi-solid, or soft foods (but also including milk feeds for non-breastfed children) the minimum number of times or more in a day) as follows: 2 times for breastfed infants 6-8.9 months; 3 times for breastfed children 9-23.9 months; and 4 times for non-breastfed children 6-23.9 months. Minimum dietary diversity was defined as the proportion of children 6-23.9 months of age who receive foods from four (4) or more food groups out of the seven (7) food groups. Minimum acceptable diet was defined as the proportion of children 6-23.9 months of age who receive a minimum acceptable diet (apart from breast-milk). This composite indicator is usually calculated from the following two fractions: Breastfed children 6-23.9 months of age who had at least the minimum dietary diversity and the minimum meal frequency during the previous day.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Health Research and Ethics Committee of Lagos University Teaching Hospital (Approval no: ADM/DCST/HREC/APP/104) and permission to conduct the research was obtained from the Local Council Development Area. Informed written consent was obtained from each respondent by explaining the purpose and content of the research and asking them to sign a consent form if they were willing to participate; before administering the questionnaire. Utmost confidentiality of information obtained was ensured by making the questionnaires anonymous and keeping data received judiciously before and after analysis.

2.3. Data collection

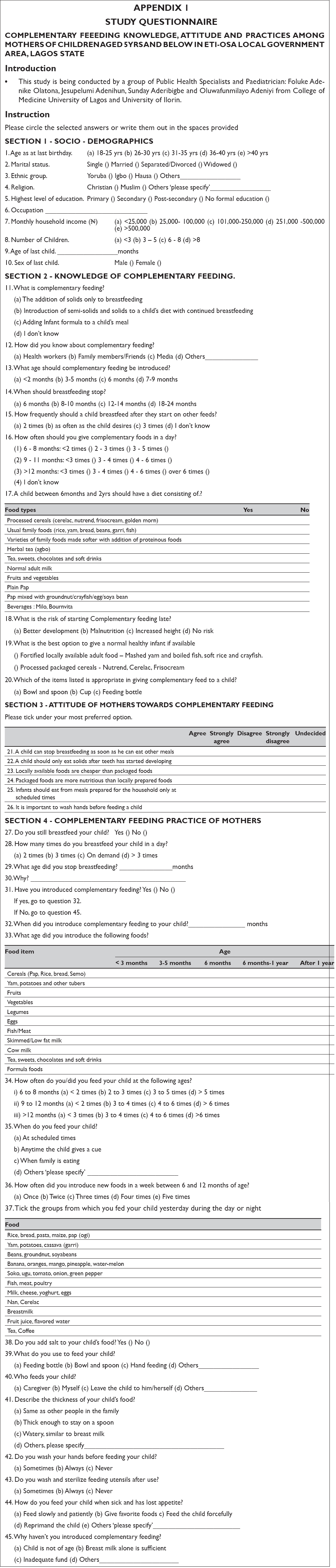

A pre-tested semi-structured interviewer administered questionnaire on complementary feeding was used to collect data on socio-demographic characteristics, knowledge of complementary feeding, complementary feeding practices and 24-hour diet recall. Appendix 1 presents the study questionnaire. Three research assistants were trained on the instrument and conducted the interview along with the researchers.

2.4. Data analysis

Data was analyzed using Epi Info Statistical software 7.1. Chi square test statistics was used to determine associations between the categorical variables and p value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Every correct answer was awarded one point while a wrong answer or “don’t know” were awarded zero point. Complementary feeding knowledge and practices were scored on a 10 and 9 point scale respectively. The knowledge scores were categorized into good (8-10), fair (5-7) and poor (0 – 4) while the practice scores were also categorized into good (7 - 9), fair (4 - 6) and poor (0 – 3). Minimum feeding frequency, minimum dietary diversity, and minimum acceptable diet were determined by deducing or calculating the statistics from the data obtained from the study.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographic characteristics

The respondents were aged between 18 and 40 years with the modal age being 26 – 30 years, 114 (32.1%). Majority of the respondents were married, 303 (85.4%) and about two-thirds, 229 (64.5%) had attained a post-secondary level of education. Almost half, 167 (47.0%) had an estimated monthly income of ₦25,000 – 100,000 ($50 - $200).

3.2. Respondents’ knowledge of complementary feeding

Majority, 257 (72.4%) of the respondents knew the correct definition of complementary feeding, 217 (61.1%) knew complementary feeding should be introduced at 6 months with only a quarter, 90 (25.4%) having correct knowledge of when breastfeeding is to stop. Majority of the respondents, 256 (72.1%) knew the child was to be breastfed on demand after starting on other feeds, but knowledge of the daily minimum frequency of complementary food was low. Only 100 (29.6%) knew a child between 6 – 8.9 months should be fed at least two times while less than half, 151 (45.9%) and 226 (63.6%) knew a child of 9 – 12months and >12months respectively should be fed at least three times daily. Majority, 219 (61.7%) knew the appropriate diet for a healthy infant was fortified local foods but less than half of the respondents, 167 (47.0%) knew malnutrition to be an associated risk of late complementary feeding. Most of the respondents, 293 (82.5%) knew the appropriate utensils for feeding. Overall, it was shown that only 53 (14.9%) of the respondents had good knowledge of complementary feeding (Table 1).

| Correct knowledge | Frequency | Percentage % |

|---|---|---|

| Correct definition of complementary feeding | 257 | 72.4 |

| Age to introduce complementary feeding (6 months) | 217 | 61.1 |

| Correct age to stop breastfeeding (18-24 months) | 90 | 25.4 |

| Frequency of child breastfeeding after starting other feeds (on demand) | 256 | 72.1 |

| Minimum frequency of giving complementary food in a day | ||

| 6-8.9 months | 100 | 29.6 |

| 9-12 months | 151 | 45.9 |

| >12 months | 226 | 63.6 |

| Most appropriate diet for normal healthy infant | 219 | 61.7 |

| Implication of starting complementary feeding late | 167 | 47 |

| Appropriate utensils for feeding | 293 | 82.5 |

| Overall level of knowledge | ||

| Good | 53 | 14.9 |

| Fair | 192 | 54.1 |

| Poor | 110 | 31 |

3.3. Factors associated with respondents’ complementary feeding knowledge

Table 2 shows that maternal age (p=0.071), marital status (p=0.071) and educational status (p=0.012) were significantly associated with complementary feeding knowledge. Mothers between the age group 36 – 40 years, women who were married and those who had tertiary education had better knowledge than others.

| Variable | N (%) | X2 | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good knowledge | Fair knowledge | Poor knowledge | |||

| Mothers’ age group (years) | |||||

| 18-25 | 5 (10.4) | 22 (45.8) | 21 (43.8) | 18.604 | 0.0171 |

| 26-30 | 11 (9.7) | 69 (60.5) | 34 (29.8) | ||

| 31-35 | 13 (12.5) | 57 (54.8) | 34 (32.7) | ||

| 36-40 | 18 (27.3) | 34 (51.5) | 14 (21.2) | ||

| >40 | 6 (26.1) | 10 (43.5) | 7 (30.4) | ||

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 48 (15.8) | 176 (58.1) | 79 (26.1) | ||

| Separated/divorced | 4 (25.0) | 4 (25.0) | 8 (50.0) | 28.612 | 0.0001* |

| Single | 1 (5.3) | 7 (36.8) | 11 (57.9) | ||

| Widowed | 0 (0.0) | 5 (29.4) | 12 (70.6) | ||

| Level of education | |||||

| Primary | 5 (29.4) | 4 (23.5) | 8 (47.1) | 16.353 | 0.012* |

| Secondary | 14 (13.7) | 51 (50.0) | 37 (36.3) | ||

| Post-secondary | 34 (14.9) | 135 (59.0) | 60 (26.2) | ||

| None | 0 (0.0) | 2 (28.6) | 5 (71.4) | ||

3.4. Complementary feeding practices among respondents

Majority of the respondents, 137 (75.3%) practiced continued breastfeeding at one year. Less than half of the respondents, 162(47.9%) practiced timely initiation of complementary food. Minimum feeding frequency (2 times) was attained by only 8 (2.0%) out of the children between 6-8.9 months whereas 117 (92.1%) and 194 (95.6%) of children between 9-11.9 months and 12-23 months respectively attained the minimum feeding frequency of 3 times.

Bottle-feeding was practiced by 40 (11.8%) of the respondents. Majority of the respondents, 285 (84.3%) fed with cups or plate and spoon while 11 (3.3%) practiced hand feeding. Two-thirds of the respondents practiced responsive feeding, 224 (66.2%) but also added salt to the meals of their children, 225 (66.6%). Majority of the respondents, 261 (73.5%) fed their children themselves with more than half of them, 192 (56.8%) giving the right consistency of meals. Hand washing before feeding was done by 290 (85.8%) and 291 (86.1%) washed utensils after use. Appropriate feeding during illness was practiced by 226 (66.9%). Only 47.0% of the mothers had good overall level of practice of complementary feeding (Table 3).

| Complementary feeding practices | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Continued breastfeeding at one year | 137 | 75.3 |

| Timely introduction of solid, semi-solid or soft Foods | 162 | 47.9 |

| Minimum meal frequency: (n=319) | ||

| 6-8.9 months (2 times) | 8 | 2.0 |

| 9-11.9 months (3 times) | 117 | 92.1 |

| 12-24 months | 194 | 95.6 |

| Bottle feeding | 40 | 11.8 |

| Hand feeding | 11 | 3.3 |

| Feeding with cup/plate and spoon | 285 | 84.3 |

| Feeding whenever child gave a cue | 224 | 66.2 |

| Correct frequency of introducing new foods per week | 41 | 12.4 |

| Adding salt to feeds | 225 | 66.6 |

| Feeding by the mother | 261 | 73.5 |

| Appropriate consistency of feeds | 192 | 56.8 |

| Always wash hands before feeding | 290 | 85.8 |

| Always wash & sterilize feeding utensils after feeding | 291 | 86.1 |

| Appropriate method of feeding during illness | 226 | 66.9 |

| Level of practice | ||

| Good practice | 167 | 47.0 |

| Fair practice | 156 | 43.9 |

| Poor practice | 32 | 9.0 |

3.5. Attainment of minimum dietary diversity and acceptable diet by the children

Only 16.0% of children between 6 and 9 months attained the minimum dietary diversity but more than half of those above 9 months, 234 (65.6%) did so. Only 4 (16.0%) of children between 6-8.9 months attained the minimum acceptable diet. About two-thirds of the children between 9-11.9 months, 79 (62.2%) and 12-24 months, 138 (68.0%) attained the minimum acceptable diet (Table 4).

| Age of child | Attained minimum dietary diversity (N=244) | Attained minimum acceptable diet (N=221) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | |

| 6-8.9 months | 4 | 16.0 | 4 | 16.0 |

| 9-11.9 months | 86 | 67.7 | 79 | 62.2 |

| 12-24 months | 144 | 70.9 | 138 | 68.0 |

3.6. Factors associated with respondents’ complementary feeding practices

Dietary diversity was not associated with either mother’s marital status or educational level or monthly household income. However, overall complementary feeding practice was statistically significantly associated with mothers’ occupation, and educational level. Mothers who had completed secondary education were more likely to have better practices than those who had not (p = 0.0036) while those who were professionals and non-manually skilled were more likely to practice appropriate complementary feeding compared to manually and non-skilled (Table 5).

| Variable | N (%) | X2 | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good practice | Fair practice | Poor practice | |||

| Mothers’ level of education | |||||

| No education | 2 (28.6) | 4 (57.1) | 1 (14.3) | ||

| Primary | 8 (47.1) | 9 (52.9) | 0 (0.0) | 19.363 | 0.0036* |

| Secondary | 55 (53.9) | 30 (29.4) | 17 (16.7) | ||

| Post- secondary | 102 (44.5) | 113 (49.3) | 14 (6.1) | ||

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | 10 (52.6) | 7 (36.8) | 2 (10.5) | 3.601 | 0.731* |

| Married | 144 (47.5) | 131 (43.2) | 28 (9.2) | ||

| Separated/divorced | 8 (50.0) | 7 (43.8) | 1 (6.3) | ||

| Widowed | 5 (29.4) | 11 (64.7) | 1 (5.9) | ||

| Occupation | |||||

| Professional | 32 (45.7) | 31 (44.3) | 7 (10.0) | ||

| Intermediate | 67 (49.3) | 65 (47.8) | 4 (2.9) | 33.775 | 0.0001* |

| Manually skilled | 14 (40.0) | 20 (57.1) | 1 (2.9) | ||

| Partly skilled | 23 (50.0) | 20 (43.5) | 3 (6.5) | ||

| Unskilled | 31 (46.3) | 19 (28.4) | 17 (25.4) | ||

| Level of knowledge | |||||

| Good knowledge | 30 (56.6) | 19 (35.9) | 4 (7.6) | ||

| Fair knowledge | 89 (46.4) | 82 (42.7) | 21 (10.9) | 4.868 | 0.301* |

| Poor knowledge | 48 (43.6) | 55 (50.0) | 7 (6.4) | ||

3.7. Factors associated with dietary diversity

None of the factors considered (marital status, maternal level of education, level of complementary feeding knowledge and monthly income) was significantly associated with dietary diversity (Table 6).

| Variable | N (%) | X2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥4 food groups | <4 food groups | |||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 11 (57.9) | 8 (42.1) | ||

| Married | 197 (65.0) | 106 (35.0) | 2.063 | 0.2412* |

| Separated/divorced | 12 (75.0) | 4 (25.0) | ||

| Widowed | 13 (76.5) | 4 (23.5) | ||

| Level of knowledge | ||||

| Good knowledge | 35 (66.0) | 18 (34.0) | ||

| Fair knowledge | 118 (61.5) | 74 (38.5) | 3.942 | 0.139 |

| Poor knowledge | 80 (72.7) | 30 (27.3) | ||

| Monthly household income | ||||

| <25, 000 | 58 (58.0) | 42 (42.0) | ||

| 25,000 – 100,000 | 109 (65.3) | 58 (34.7) | 6.707 | 0.1522 |

| 101,000 – 250,000 | 43 (78.2) | 12 (21.8) | ||

| 251, 000 – 500,000 | 10 (71.4) | 4 (28.6) | ||

| >500,000 | 13 (68.4) | 6 (31.6) | ||

| Level of education | ||||

| Primary | 14 (82.4) | 3 (17.7) | ||

| Secondary | 72 (70.6) | 30 (29.4) | 4.655 | 0.2130* |

| Post –secondary | 142 (62.0) | 87 (38.0) | ||

| None | 5 (71.4) | 2 (28.6) | ||

4. Discussion

According to WHO, complementary feeding is the period wherein there is a transition from exclusive breastfeeding to family foods although breastfeeding is still continued.[18] Knowledge of timing of complementary feeding was high similar to findings in Lahore city in Pakistan (54%), Karachi (57.2%) and Ghana (60.0%).[19-21] Only about one quarter of the respondents knew the age when breastfeeding should be discontinued to be 18-24 months. This is far below what was obtained in Pakistan where most of the respondents knew the right time breastfeeding should be discontinued.[20] The World Health Organization recommends that children be fed at least 2 times daily between 6-8 months and at least 3 times for children between 9-12 months and >12months of age. Only about half of the mothers in our study knew the correct frequency unlike in Ghana where almost all the mothers knew the correct frequency.[21] Overall knowledge of the respondents on complementary feeding was low similar to reports from Lahore in Pakistan (24.0%) and Kenya (33.5%). [8, 26]

The influence of socio-demographic factors on infant feeding knowledge has been documented in literature. Older mothers’ age, being married and higher level of education were significantly positively associated with increased level of knowledge (p<0.05) (p<0.05). This implies that maturity, being married, and education are important factors in mothers’ knowledge of complementary feeding. The prevalence of timely initiation of complementary feeding was low 47.9%. This is consistent with other studies from Lagos (48.4%),[15] Cameroon (46.5%),[23] Lahore (43%)[19] and India (40%).[24] Higher prevalence were however recorded in Ghana, Eastern Ethiopia, and Nairobi where 79.1%, 66.9%, 60.5%, and introduced complementary foods at 6 months respectively.[20,25,26]

Though late initiation of complementary feeding has been identified as a cause of malnutrition less than half of the respondents in this study knew malnutrition as an outcome of late commencement of complementary feeds. Reports from other countries in Africa have also corroborated this low level of knowledge with even lower figures compared to our study.[22] This may be as a result of misconceptions that breast milk alone is sufficient even after 6 months of age for growth and development.

Most of the mothers knew that bowl and spoon were the most appropriate feeding utensils and majority used them similar to other studies in Lagos.[15] Bottle feeding and hand feeding were practiced by few respondents (11.8% and 3.3% respectively). This is in contrast to what was observed in Sudan where 59.2% fed their children with their hands.[27] The lower figure obtained from this study could be because most of the respondents are educated and no longer practice traditional method of feeding. Only the level of education and occupation of the mothers significantly influenced the complementary feeding practices similar to reports from other researchers.[18] Mothers who had completed secondary education and non-manually skilled had better complementary feeding practices than those who were manually or non-skilled.

The minimum dietary diversity (eating from at least four food groups out seven) was low among children aged 6 to 9 months. This finding is consistent with other studies from India and Nairobi.[24,26] A certain Nigerian study on the trends of complementary feeding indicators has also shown that among educated mothers, minimum dietary diversity worsened from (33% to 24%) while minimum acceptable diet worsened from 13% to 8%.[12] None of the factors considered in this study (marital status, mother’s education, maternal knowledge of complementary feeding and monthly income) was significantly associated with minimum dietary diversity, however, other studies indicate that Mothers education, age of a child, birth order of index child, living in urban area, having home gardening, maternal knowledge of infant and young child feeding, husbands’ direct involvement in feeding and media exposure were positively associated with dietary diversity.[28,29] The importance of dietary diversity cannot be overemphasized in complementary feeding because research consistently indicates its significant and positive influence on the likelihood of adequate consumption of food nutrients.[30]

Limitations of the study

Mothers of under-five children were assessed rather than mothers of children aged 6 to 23.9 months which is the age-group that need complementary feeding. This implies that some parameters which should have been based on 24-hour diet recall which were based on ordinary recall (among mothers whose children were above 24 months) could have been affected by recall bias. Moreover, since the study was cross-sectional, cause and effect between independent and dependent variables were difficult to determine therefore determinants of suboptimal complementary feeding knowledge, practices and dietary diversities could not be ascertained.

5. Conclusion and Global Health Implications

Complementary feeding knowledge was low similar to results from other studies in Lahore and Ghana.[19,21] Complementary feeding practices, minimum dietary diversity and acceptable diet were not at the optimal level when compared with the recommendations of the WHO. Appropriate complementary feeding education emphasizing timely initiation and meal diversity is necessary to improve knowledge and feeding practices of mothers especially the young, single and uneducated ones.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Chairman of Eti-Osa Local Government Area of Lagos State (2016) for his support without which data collection from the mothers in the communities would have been very difficult.

Conflict of Interest: Authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval: Study was approved by two Institutional Review Boards.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from the study participants.

Funding: The research was funded by all the authors.

REFERENCES

- 2016. World Health Organization Infant and young Child feeding. http://who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs342/en/

- Maternal and child under nutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet. 2008;371:243-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Infant and young child feeding: Model Chapter for textbooks for medical students and allied health professionals. Geneva: WHO; 2009.

- Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey. Abuja, Nigeria and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICF International; 2013.

- Hypertension, Diabetes and Overweight: Looming Legacies of the Biafra Famine. Plos One 2010 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013582

- [Google Scholar]

- Breastfeeding as obesity prevention in the United States: a sibling difference model. American Journal of Human Biology. 2010;22(3):291-6. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20982

- [Google Scholar]

- Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices. Conclusions of a consensus meeting held 6-8 November 2007 in Washington D.C., USA. 2008. p. :2.

- Complementary feeding--reasons for inappropriateness in timing, quantity and consistency. Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2008;75(1):49-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Appropriate complementary feeding practices and associated factors among mothers of children age 6–23 months in Southern Ethiopia 2015. BMC Pediatrics. 2016;16:131. doi: 10.1186/s12887-016-0675-x

- [Google Scholar]

- Ghana Demographic and Health Survey. Rockville, Maryland, USA: GSS, GHS, and ICF International; 2014.

- Trends in complementary feeding indicators in Nigeria 2003-2013. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008467. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008467

- [Google Scholar]

- Using local health information to promote public health. Health Affairs. 2006;25:4979-991. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.4.979

- [Google Scholar]

- Mother’s knowledge and practice of breastfeeding and complementary feeding in Enugu State Nigeria. Journal of Research in Nursing and Midwifery. 2016;5:021-029. DOI: http:/dx.doi.org/10.14303/JRNM.2015.0127

- [Google Scholar]

- Complementary feeding practices among mothers of children under five years of age in Satellite Town, Lagos, Nigeria. Food and Public Health. 2014;4(3):93-98. DOI: 10.5923/j.fph.20140403.04

- [Google Scholar]

- Nigeria demographic and health survey, MD USA, NPC and ORC Macro Calverton 2007:163-174.

- Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices. part 3: country profiles 2010:5-10.

- Complementary feeding. www.who.int/elena/titles/complementary_feeding/en/last updated March 2016

- Knowledge and practices of mothers for complementary feeding in babies visiting pediatrics outpatient department of Jinnah hospital, Lahore. Biomedical Journal. 2013;29:221-230.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge attitude and practice of mothers regarding complementary feeding. Journal of the Dow University of Health Sciences. 2014;8(1):21-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Child feeding knowledge and practices among women participating in growth monitoring and promotion in Accra, Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:180.

- [Google Scholar]

- JK Determinants of complementary feeding practices and nutritional status of children 6-23months old in Korogocho slum, Nairobi County, Kenya. M.Sc thesis. University of Kenyatta 2013

- Feeding Practices Food and Nutrition Insecurity of infants and their Mothers in Bangang Rural Community, Cameroon. Journal of Nutrition and Food Sciences. 2014;4:264. doi:10.4172/2155-9600.1000264

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of complementary feeding practices and misconceptions regarding foods in young mothers. International Journal of Food and Nutritional Sciences. 2013;2(3):85-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bogale A: Complementary feeding practice of mothers and associated factors in Hiwot Fana Specialized Hospital, Eastern Ethiopia. Pan African Medical Journal. 2014;18:143.

- [Google Scholar]

- Correlates of complementary feeding practice among caregivers of infants and young children aged 6-24 months at Mbagathi district hospital, Nairobi. M.Sc thesis. University of Nairobi 2012

- [Google Scholar]

- Infants feeding and weaning practices among mothers in Northern Kordofan state, Sudan. European Scientific Journal. 2014;10(24):165-181.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dietary diversity, meal frequency and associated factors among infant and young children in Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1007.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of dietary diversity in children ages 6 to 23 months in largely food-insecure area of South Wollo, Ethiopia. Nutrition. 2016;33:163-168.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors Influencing Nutritional Adequacy among Rural Households in Nigeria: How Does Diversity Stand among Influencers? Ecology of Food and Nutrition. 2017;31:1-17. doi: 10.1080/03670244.2017.1281127

- [Google Scholar]