Translate this page into:

Effectiveness of a 24/7 Dad® Curriculum in Improving Father Involvement: Profiles of Engagement

∗Corresponding author email: rwilson2@health.usf.edu

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background or Objectives:

Father involvement is a key component in maintaining healthy families and communities. This study presents quantitative results of the first five years of a comprehensive fatherhood training program offered by REACHUP, Inc. in Florida, United States.

Methods:

The program utilized the 24/7 Dad ® curriculum for the fatherhood training program. Key program outcome was differences in pre and post-test scores on self-awareness, fathering skills, parenting skills, relationship skills, and self-care. Demographic and pretest-posttest data collected between 2013 and 2017 were analyzed using chi-square test for categorical variables, McNemar’s test for differences in proportions pre- and post-intervention, paired sample t-test to compare means in pretest and posttest scores and analysis of variance (ANOVA) to test the difference between means across years and demographic characteristics.

Results:

Attendance in the program increased yearly, nearly doubling from 55 participants in 2013 to 97 in 2017. The mean pretest score was 8.90 (±4.04) and the mean posttest score was 16.42 (±4.54) out of 22 total points, representing a highly significant positive effect of the program on self-awareness, fathering skills, parenting skills, relationship skills and self-care which will enable men to establish long-lasting positive relationships with their children. There were significant differences by demographic characteristics. Younger participants tended to score lower on the pretest but made the most knowledge gains following the training as indicated by the difference in pre- and posttest scores (<0.001).

Conclusion and Global Health Implications:

Increasing yearly attendance indicates the notion of male involvement is gaining momentum. An important lesson learned over the five-year period is that not all males who participated in the program were biological fathers of infants, young children or adolescents. Many participants were grandfathers, uncles and family friends, indicating that the benefits of a male involvement program can extend beyond the boundaries of biological fatherhood.

Keywords

Father Involvement

Fatherhood

Self-awareness

Fathering skills

Parenting skills

Relationship skills

Self-care.24/7 Dad®

Curriculum

Program Evaluation

REACHUP

Inc

1. Introduction

1.1. Background of the Study

Father involvement is a key component in maintaining healthy families and communities. Children with positive male influences in their lives develop better friendships, achieve greater academic success, experience fewer behavioral problems, and have higher self-esteem.1-7 Previous research suggests that father involvement positively impacts the social, behavioral, emotional, psychological and cognitive outcomes of children resulting in better life satisfaction outcomes.2-4 These positive end-points have been shown to persist from infancy to adulthood even when controlling for maternal involvement.4,5,8

From 1960 to 2016, children living in father-absent homes tripled from 8% to 23%.9 Disproportionately high rates of father-absent homes have been reported in African-American (48.5%) compared to Hispanic (26.3%) and white (18.3%) households.10 Children from father- absent homes are at increased risk of negative outcomes in mental health, physical health, social behavior and development, and economic mobility resulting in greater risk of infant mortality, child abuse and neglect, teenage pregnancy, alcohol and drug abuse, incarceration, and poverty.4,11-15 These effects have great potential for a longer lasting impact if father absence begins early in childhood.15-19

1.2. Objectives of the Study

Considering the significant impact of paternal presence or absence on infant, maternal, family, and community outcomes, many community-based organizations that have previously focused primarily on programs to support mothers and babies have thus, expanded their reach to include men. One such organization is REACHUP, Incorporated, a not-for-profit (501c3) organization in the Tampa Bay area, that has provided services in the historically underserved area of Central Tampa, Florida, for more than 12 years and currently hosts more than 12 community-focused programs. The target area for REACHUP, Inc. programs is comprised of a population of about 102,181 inhabitants,20,21 with a racial/ethnic composition of approximately 60% African American; 18.3% white; 12.1% Hispanic; and 9.6% residents of other racial/ethnic groups.22 Nearly 56.0% of all births are to black mothers who are typically young, unmarried, undereducated, and Medicaid-eligible.22,23 Compared to the rest of the county, families in the project area tend to receive half the county median income and experience double the unemployment rate.23 REACHUP’s programs strive to address these disparities by promoting equality in healthcare and positive health for families. Two of the 12 programs provided by REACHUP, Inc. focus specifically on males and strengthening their connection to family and community. This paper describes the first five years of the fatherhood training program provided by REACHUP, Inc.

2. Methods

REACHUP utilizes the 24/7 Dad® curriculum developed by the National Fatherhood Initiative (NFI) for their fatherhood training program. The curriculum is evidence-based and encourages fathers to be involved, responsible and committed to their children 24 hours 7 days a week.24-26 The program is built around five domains: (1) self-awareness, (2) fathering skills, (3) parenting skills, (4) relationship skills, and (5) self-care which enable men to establish long-lasting positive relationships with their children. The 24/7 Dad® curriculum is typically delivered 2 hours per week over a 12 week period21,22 but can be modified or tailored to meet local needs.

Participants in the fatherhood training program at REACHUP are recruited by various means including radio advertisements, brochures, community agency referrals and word of mouth. Men are eligible for participation in the program based on their zip code of residence. Currently, the 5 eligible zip codes cover the entirety of Central Tampa, Florida. For ease of participation, different community partners across Central Tampa host the program from year to year. These community partners include local community centers, churches, and workforce development centers.

2.1. Study Variables

Once participants are enrolled in the program, socio-demographic data are collected (e.g. age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, etc.). A 22-item knowledge and skills instrument developed by NFI is administered at baseline (pretest) and after the training (posttest). The scale measures aspects of self-awareness, care of self, fathering skills, parenting skills and relationship skills.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

To examine the characteristics of program participants over the first 5 years of the program at REACHUP and how the characteristics might have changed over time, the following descriptive statistics techniques were utilized: chi-square for categorical variables, McNemar’s test for differences in proportions pre- and post-intervention, paired sample t-test to compare means in pretest and posttest scores and analysis of variance (ANOVA) to test the difference between means across years and demographic characteristics. SPSS, version 24, was used for statistical analysis and a p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

2.3. Ethical Approval

This project was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of South Florida.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characterisitcs Results

Between 2013 and 2017, four-hundred and nine men attended the fatherhood training. Attendance in the program increased yearly, nearly doubling from 55 participants in 2013 to 97 in 2017. Table 1 displays the demographic characteristics of program participants and compares the differences from 2013 to 2017. Over the five-year timeframe, program participants ranged in age from 16 to 85 years with a mean age of 36.36 (±12.92) years; however, the mean age in 2017 was 32.65 (±10.50) years, representing nearly a seven-year decrease from the 2013 cohort’s mean age of 39.42 (±15.10). Additionally, the 2017 cohort was comprised of a more racially and ethnically diverse group of male participants as compared to the participants in 2013. Levels of education changed significantly over the years, with fewer participants in 2017 reporting an advanced degree and more reporting not having received a high school diploma or GED. This relationship persisted when analysis of education was restricted to participants 19 years of age and older (data not shown). More than three-quarters of all participants were fathers to children under 18 years of age. Men in the 2017 cohort were less likely than the participants in 2013 to be married (19.6% compared to 27.8%, respectively (p <0.0001)) but more likely to reside in a two-parent household, indicating the tendency to cohabitate in the absence of marriage. The majority of participants in both cohorts were unemployed; however, those in 2017 were significantly less likely to report a household income of more than $50,000 a year.

| Characteristic | Total n=409(%) | 2013 n=55 (%) | 2017 n=97 (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 36.36 (±12.92) | 39.42 (±15.10) | 32.65 (±10.50) | <0.001 |

| Race | <0.001 | |||

| Black | 251 (61.5) | 44 (80.0) | 43 (44.3) | |

| White | 95 (23.2) | 8 (14.5) | 34 (35.1) | |

| Other | 22 (5.4) | 2 (3.6) | 7 (7.2) | |

| Refused | 41 (10.0) | 1 (1.8) | 13 (13.4) | |

| Ethnicity | <0.001 | |||

| Hispanic | 85 (20.7) | 5 (9/1) | 30 (30.9) | |

| Education | 0.001 | |||

| <High school | 58 (14.6) | 6 (10.9) | 18 (18.9) | |

| High school/GED | 139 (34.4) | 13 (23.6) | 33 (34.7) | |

| Technical school | 29 (7.2) | 2 (3.6) | 7 (7.4) | |

| Some college | 96 (23.8) | 24 (43.6) | 10 (10.5) | |

| Advanced degree | 24 (5.9) | 6 (10.9) | 3 (3.2) | |

| Father of child<18yrs | 0.285 | |||

| Yes | 333 (81.4) | 45 (83.3) | 72(74.2) | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | |||

| Married | 127 (31.1) | 15 (27.8) | 19 (19.6) | |

| Household structure | <0.001 | |||

| Two parent | 160 (39.3) | 16 (29.1) | 37 (38.1) | |

| Male Single | 129 (31.5) | 19 (34.5) | 23 (23.7) | |

| Employed | 0.833 | |||

| Yes | 162 (39.6) | 21 (38.9) | 34 (35.1) | |

| Income | 0.002 | |||

| <$10,000 | 130 (31.7) | 16 (29.1) | 29 (29.9) | |

| $10,000-$29,999 | 62 (15.4) | 7 (12.7) | 11 (11.3) | |

| $30,000-$49,000 | 38 (9.0) | 7 (12.7) | 9 (9.3) | |

| $50,000+ | 33 (8.0) | 9 (16.4) | 1 (1.0) | |

| R efused | 146 (35.9) | 16 (29.1) | 47 (48.5) | |

3.2. Main Variable (Dependent or Outcome) Results

Three hundred and thirty-one men completed the training between 2013 and 2017 (Table 2). The mean pretest score was 8.90 (±4.04) and the mean posttest score was 16.42 (±4.54) out of 22 total points. Analysis of pre-and posttest scores indicated significant differences by demographic characteristics. Younger participants tended to score lower on the pretest but made the most knowledge gains following the training as indicated by the difference in pre- and post-test scores. Individuals reporting lower education levels scored lower on the pretest and made the most gains on the posttest. Fathers of children less than 18 years of age scored higher on the pretest but individuals who did not have children less than 18 years of age made the most knowledge gains. Notably, participants who refused to provide information on marital status, household structure or income also appeared to benefit greatly from the program as indicated by the significant difference in their pre- and posttest scores compared to other participants.

| Characteristic | Pre-test n=334 Mean (SD) | p-value | Post-test n=331 Mean (SD) | p-value | Difference n=334 Mean (SD) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age groups | <0.001 | 0.040 | <0.001 | |||

| ≤20 | 4.70 (2.98) | 17.43 (5.85) | 12.74 (6.70) | |||

| 21-25 | 8.76 (4.12) | 18.02 (3.62) | 9.27 (5.33) | |||

| 26-29 | 8.62 (3.31) | 15.86 (4.73) | 7.24 (5.30) | |||

| 30-39 | 9.56 (3.71) | 16.33 (4.41) | 6.76 (4.44) | |||

| 40+ | 9.31 (4.25) | 15.82 (4.51) | 6.51 (4.56) | |||

| Race | 0.173 | 0.010 | 0.034 | |||

| Black | 9.06 (3.98) | 17.02 (4.21) | 7.95 (5.15) | |||

| White | 9.15 (4.11) | 15.26 (4.30) | 6.11(4.62) | |||

| Other | 8.71 (4.26) | 17.24 (4.58) | 8.52 (6.38) | |||

| Refused | 7.49 (3.94) | 15.40 (6.02) | 7.91 (5.35) | |||

| Ethnicity | <0.001 | 0.358 | 0.007 | |||

| Hispanic | 7.63 (3.89) | 15.78 (5.62) | 8.15 (5.08) | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 9.88 (3.81) | 16.68 (3.98) | 6.79 (4.73) | |||

| Refused | 7.47 (4.07) | 16.37 (4.73) | 8.90 (6.08) | |||

| Education | <0.001 | 0.538 | <0.001 | |||

| <High school | 8.64 (3.97) | 16.17 (4.88) | 7.53 (5.69) | |||

| High school/GED | 8.60 (3.72) | 16.11 (4.27) | 7.50 (4.87) | |||

| Technical school | 9.78 (2.88) | 16.70 (4.52) | 6.91 (4.00) | |||

| Some college | 10.54 (3.60) | 17.12 (3.94) | 6.58 (4.32) | |||

| Advanced degree | 12.17 (3.17) | 17.00 (3.25) | 4.82 (4.28) | |||

| Father of child<18yrs | <0.001 | 0.097 | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 9.32 (3.93) | 16.19 (4.61) | 6.88 (4.72) | |||

| No | 7.43 (4.08) | 17.19 (4.23) | 9.76 (6.01) | |||

| Marital status | <0.001 | 0.084 | 0.004 | |||

| Married | 9.79 (3.98) | 17.22 (4.27) | 7.42 (4.93) | |||

| Single/Separated | 8.87 (3.77) | 15.99 (4.65) | 7.13 (4.96) | |||

| Refused | 6.10 (4.77) | 16.57 (4.38) | 10.47 (6.45) | |||

| Household structure | 0.078 | 0.007 | <0.001 | |||

| Two parent | 8.90 (4.36) | 17.20 (4.44) | 8.30 (5.32) | |||

| Male single | 9.45 (3.78) | 15.85 (4.32) | 6.39 (4.23) | |||

| Other | 8.81 (3.61) | 15.16 (4.68) | 6.35 (5.29) | |||

| Refused | 7.40 (4.03) | 17.43 (4.67) | 10.03 (5.70) | |||

| Employed | 0.023 | 0.100 | 0.744 | |||

| Yes | 9.54 (4.09) | 16.94 (4.17) | 7.40 (5.07) | |||

| No | 8.50 (3.97) | 16.10 (4.72) | 7.59 (5.24) | |||

| Income | <0.001 | 0.065 | 0.002 | |||

| <$10,000 | 9.71 (3.68) | 16.37 (4.29) | 6.67 (4.41) | |||

| $10,000-$29,999 | 10.66 (3.28) | 17.58 (3.57) | 6.92 (4.21) | |||

| $30,000-$49,000 | 9.38 (2.96) | 15.97 (4.22) | 6.59 (4.45) | |||

| $50,000+ | 11.37 (3.79) | 17.67 (3.47) | 6.30 (4.59) | |||

| Refused | 6.65 (3.94) | 15.73 (5.29) | 9.08 (6.10) | |||

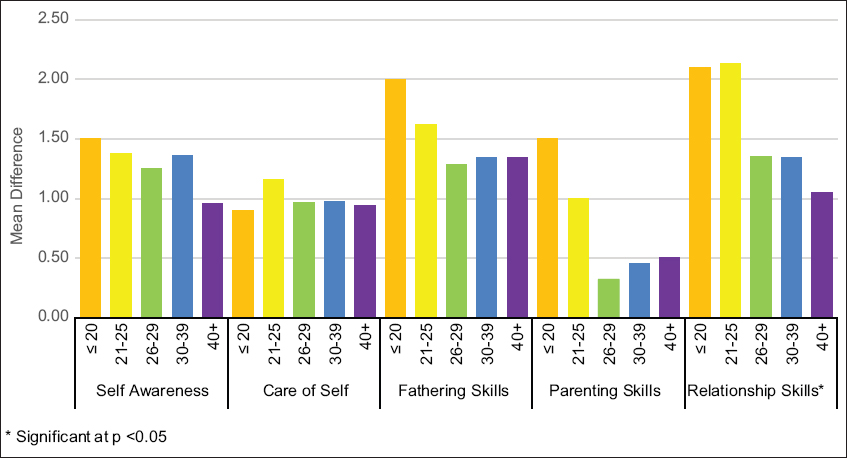

Examining pre- and post-test scores by the five domains in the curriculum (self-awareness, fathering skills, parenting skills, relationship skills and self-care) indicated that younger participants tended to make the most gains in all areas (Figure 1). However, the most significant gains for younger participants were in the relationship skills domain. Examining pre- and post-responses on individual test items demonstrated areas where the curriculum was most and least effective in educating participants or altering perceptions regarding fatherhood in this population. Following the training, significantly more participants were able to identify the traits of an ideal father, the benefits of marriage, and where individuals learn what it means to be man. The training did not significantly change perceptions related to how a dad provides for his family, the purpose of family rules or the best definition of self-worth.

- Acquisition of fatherhood knowledge according to participant age and knowledge domains

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion

This analysis of the first five-years of REACHUP’s fatherhood training program provided valuable insights into the utility of a community-based fatherhood training program. Overall, participation in the program increased knowledge regarding important fatherhood concepts among men of all age groups but was significantly effective among younger participants. Increasing yearly attendance rates was an indication that the notion of male involvement was gaining momentum and the program was progressively attracting younger and racially/ethnically diverse participants.

Evaluation of the fatherhood training program also highlighted the changing dynamics of family and family units. Participants in the 2017 cohort were less likely to be married but more likely to report rearing children in a two-parent household. This demonstrates the growing trend of unmarried cohabitation in the United States.10 Notably, not all males who participated in the program were biological fathers of infants, young children, or adolescents. Many were grandfathers, uncles and family friends, thus demonstrating that the benefits of father involvement could extend beyond biological boundaries.

To enhance the services provided to program participants, REACHUP, Inc. introduced a series of health screening questions into the program enrolment forms and provides limited case management services to help connect men with available health services. Additionally, men were eligible to participate in a stress reduction program designed to help participants develop healthy coping mechanisms to address their stress. Unfortunately, program participants were impacted by high unemployment rates, a reflection of the current situation of the source community. This indicates a need to expand fatherhood training programs to more adequately address the social determinants of health that will allow fathers to thrive beyond program completion.

4.2. Recommendation for Further Studies

Recommendations for next steps include long-term follow-up to determine if increased knowledge translates into skill acquisition or behavior change and to determine how socio-economic and neighborhood factors influence fatherhood.

5. Conclusion and Global Health Implications

This evaluation indicates the 24/7 Dad ® curriculum is effective in increasing fatherhood knowledge. Increasing knowledge is the first step to changing behaviors and helping fathers remain positively engaged in their children’s lives. This work has global implications as healthy father involvement is critical for all children across the globe.

Acknowledgements

None.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Funding/Support: This work was supported in part by project H49MC12793 from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau (Title V, Social Security Act), Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), US Department of Human and Health Services. Allegany Francis Funding. The funding agencies did not play any role in any aspect of the analyses.

Ethical Approval: Approved by the University of South Florida IRB as non-human research.

References

- Paths to Father Involvement:The Early Head Start Fatherhood Demonstration in Its Third Year Final Report. US Department of Health and Human Services, Head Start Bureau 2004

- [Google Scholar]

- Fathers'involvement and children's developmental outcomes:a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Acta Paediatr. 2008;97(2):153-158.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effects of father involvement:A summary of the research evidence. The FII-ONews. 2002;1(1-11)

- [Google Scholar]

- The History of Research on Father Involvement. Marriage &Family Review. 2000;29(2-3):23-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fatherhood Institute:supporting fathers to play their part. Community Practitioner. 2015;88(1):13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fathers'influence in the lives of children with adolescent mothers. J ournal of Family Psychology. 2006;20(3):468-476.

- [Google Scholar]

- Scholarship on Fatherhood in the 1990s and Beyond. J ournal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62(4):1173-1191.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2016. 2016 Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/sahie/technical-documentation/model-input-data/cpsasec.html

- Living Arrangements of Children Under 18:Tables CH-2, CH-3, CH-4. 1960-Present In 2012

- [Google Scholar]

- National Fatherhood Initiative. http://www.fatherhood.org/

- Paternal Absence and Child Behavior:Does a Child's Gender Make a Difference? J ournal of Marriage and the Family. 1997;59(1):103.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2006. Child Abuse and Neglect User Manual Series. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubpdfs/fatherhood.pdf

- Fatherhood ideals in the United States:Historical dimensions. In: Lamb M, ed. The role of the father in child development. Vol 1997. New York: John Wiley &Sons; p. :33-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Changing Role of Fatherhood:The Father as a Provider of Self-Object Functions. Psychoanalytic Social Work. 2011;18(2):107-125.

- [Google Scholar]

- Father involvement in early childhood programs:review of the literature. Early Child Development and Care. 2008;178(7-8):745-759.

- [Google Scholar]

- Why Could Father Involvement Benefit Children?Theoretical Perspectives. Applied Developmental Science. 2007;11(4):196-202.

- [Google Scholar]

- Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml

- State and County Quick Facts 2000. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045216/00

- Healthy Start Program and Feto-Infant Morbidity Outcomes:Evaluation of Program Effectiveness. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2008;13(1):56-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening for Perinatal Depression With Limited Psychiatric Resources. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2005;11(6):359-363.

- [Google Scholar]

- Male Involvement Network. https://www.reachupincorporated.org/portfolio/male-involvement-network/

- 24/7 Dad®program in Hawai'i:Sample, design, and preliminary results. Center on the Family, University of Hawai'i at Manoa 2015

- [Google Scholar]

- 24/7 Dad™A.M. and 24/7 Dad™P.M. Outcome Evaluation Results 2005-2006. National Fatherhood Initiative 2006

- [Google Scholar]