Translate this page into:

Geospatial Analysis of Parental Healthcare-Seeking Behavior in the Vicinity of Multispecialty Hospital in India

*Corresponding author: Sunil Kumar Panigrahi, Department of Community & Family Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Deoghar, Jharkhand, India. Tel: +918424017937 sunil1986panigrahi@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Pal A, Panigrahi SK, Parija PP, Majumdar S. Geospatial analysis of parental healthcare-seeking behavior in the vicinity of multispecialty hospital in India. Int J MCH AIDS. 2024;13:e014. doi: 10.25259/IJMA_628

Abstract

Background and Objective

The healthcare-seeking behavior of vulnerable groups, such as children under five, depends on a multitude of factors, including the caregiver’s decision making. Approximately 60% of Indians seek care from private hospitals. Recent health policy in India has favored the establishment of multispecialty hospitals. However, it remains unclear to what extent this policy has changed the number of Indians seeking healthcare from these government-established multispecialty hospitals. The study aims to assess the health-seeking behavior of parents of children under five in the vicinity of a public multispecialty tertiary care hospital.

Methods

This was a community-based cross-sectional survey with geospatial mapping conducted among the parents of children under five using a semi-structured questionnaire in Epi-collect mobile app. The study site was an urban slum in a catchment area [within five kilometers (km)] of a multispecialty tertiary care public hospital in the central Indian state of Chhattisgarh. The study was conducted for one year duration from February 2019 to January 2020. A questionnaire was administered to the parents of the children under five (N = 353) after their household confirmation from the nearby Anganwadi center, the community level service providing center under the Integrated Child Development Scheme by the Ministry of Women and Child Development (WCD). The questionnaire included sections for demographic characteristics, the illness pattern among their children, health-seeking decision-making, and more. Descriptive analysis was presented with numbers and percentages. Univariate analysis was used to assess the association between sociodemographic variables and health-seeking characteristics. Statistical significance was considered at p value less than 0.05. We used geospatial mapping using coordinates collected and compiled using the Microsoft Excel version 2021 and analyzed using QGIS (Quantum Geographic Information System) software.

Results

Among the parents interviewed patients (N = 353), maternal literacy rates were over 85%. Approximately 54% of the families were below poverty line. Among 95.2% of the families, mothers were part of decision-making regarding their children’s health-seeking. Over 92% of the families opted for consultation in a nearby private hospital or dispensary. Geospatial mapping of private hospitals was a favored place for healthcare-seeking by mothers, irrespective of their socioeconomic status or education rather than multispecialty hospital.

Conclusion and Global Health Implications

The majority of the parents in the vicinity of public multispecialty hospitals seek care from private clinics for ailments for children under five. The establishment of public multispecialty tertiary care hospitals, which are mandated for tertiary level of care and research, cannot replace primary-level healthcare institutions, showed that private hospitals were the favored places healthcare seeking by mothers. These primary-level institutions are critical for the management of common ailments for children under five near home and reducing the financial burden on the family, even in the vicinity of a multispecialty hospital.

Keywords

Healthcare-Seeking Behavior

Geographical Information Systems

Child

Preschool

INTRODUCTION

The healthcare-seeking behavior of a person determines the overall health. It is defined as “any action or inaction undertaken by individuals who perceive themselves to have a health problem or to be ill for the purpose of finding an appropriate remedy.”[1,2] According to the health-seeking behavior model, the antecedents (social environment, cultural environment, economic factors, and health service availability) affect the attributes (interaction, intellectual process, decision-making, and ability to measure or assess), which, in turn, have a wide-ranging impact on health consequences of disease.[3] Healthcare-seeking for an economically independent adult mostly depends on his wish and decision-making. In the case of populations from vulnerable age groups, like children under five, elderly persons, and pregnant mothers, it depends on a multitude of factors. These may include the decision-makers in the family, the socioeconomic class of the family, or family priorities and needs, and so on.

National family health surveys have repeatedly shed light on the inadequacy of health-seeking by caretakers or parents of children under five.[4,5] The parents were seeking healthcare after 24 hours in as high as 30% of the common childhood illnesses. The healthcare-seeking for children under five is always preceded by decision-making by the parents.[6] Inappropriate health decision-making and care-seeking not only puts the child at risk of developing complications but also puts an unnecessary financial burden on the family. The majority of parents seek care in private hospitals nearer to their homes for children under five ailments in India.[7–10] The reasons are multitude and complex. These might be due to quick accessibility or availability of quality care in private hospitals, or longer waiting periods, or lack of trust in public hospitals. Many of the private healthcare-seeking by people invariably leads to the financial burden on the poor and also affects healthcare utilization in public healthcare institutions.[7,11]

The reduction of financial burden through reduction of out-of-pocket expenditure in healthcare as envisaged by the Government of India is through health insurance and establishment of affordable tertiary healthcare centers, that is, multispecialty teaching hospitals through centrally sponsored Prime Minister’s Health Protection Schemes like Pradhanmatri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY) or Pradhanmatri Swasthya Surakha Yojana (PMSSY), respectively.[12,13] Health policy decision-making in low- and middle-income countries is more favored toward the establishment of tertiary care multispecialty hospitals as compared to improving the primary healthcare approach, especially in urban areas and cities.[14,15] After the establishment of 22 tertiary care multispecialty hospitals across the country under PMSSY, there is a dearth of understanding of how these hospitals have affected or changed the health-seeking of the adjoining population they are catering to. The availability of high-quality health services in the vicinity is one of the antecedents which is presumed to improve the decision-making by early health-seeking and early diagnosis.[3]

The research question is to know the geographical distribution of health decision-making by parents of a child under five. We wanted to assess the type and demographic factors associated with healthcare-seeking among the mothers of children under five in an urban slum in the vicinity of a public multispecialty tertiary care teaching hospital and also to assess the geospatial distribution of the same. Among various antecedents of health-seeking behavior, we focus on issues related to health services and availability for assessment of health decision-making.[3]

METHODS

This study is a community-based cross-sectional survey using geospatial mapping. The study site is a randomly selected urban slum out of four urban slums in the catchment area of a multispecialty teaching hospital in the central state of Chhattisgarh, India. The study population was children under five residing in the slum for at least six months in the area. Children under five, suffering from any congenital anomalies, mental or developmental anomalies, or severely ill, were excluded from the study. The information was collected digitally using Epicollect5[16] through a house-to-house survey from the mothers of children under five.

The minimum sample size was calculated (n = Z2pq/d2) as 350 using the proportion of children under five as 15%, 4% absolute precision, and 10% nonresponse rate.[17] The line listing of less than five-year-old children were done from the registers of Anganwadi centers present in the slum. Among them, total of 353 children under five were selected through simple random sampling using the random number generation technique. The information was collected using a semi-structured questionnaire, prepared and developed after the literature review on the topic, before transcribing in Epicollect 5 mobile application. Each of the children under five was visited and approached to be included in the study. All those who were absent or did not respond for three visits were excluded from the study after applying. For all those who were absent, a new random set of numbers was selected and included in the study. The final analysis of the study included N = 353 number of children under five, with the informant being the mother of the children.

The primary outcome of the study was the type of hospitals where the parents seek care for their children (private hospitals/dispensaries/nursing homes or public tertiary care hospitals/dispensaries/urban health centers). Other variables of those assessed were demographic information like the gender of the child, age, education, and income of the mother, education of the father, presence of below poverty line (BPL) card, and decision-maker for child health.

We draw on the theoretical framework of health-seeking behavior model and assess the pattern of change in decision-making after a change in one of the antecedents of health-seeking behavior, that is, accessible health services.[3]

The data was collected from 353 mothers using Epicollect5,[16] exported to Microsoft Excel version 2021, and analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Descriptive analysis was presented with numbers and percentages. A chi-square test of significance (two-sided) was applied to test the associations between private healthcare-seeking and demographic variables. Statistical significance was considered at p value less than 0.05. We used geospatial mapping using coordinates collected and compiled using the Microsoft Excel version 2021 and were analyzed using QGIS.[18] The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC), All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Raipur, India. The content of assent and consent were provided to the participants in a vernacular language, that is, Hindi. The subjects were enrolled only after obtaining informed written consent and assent form from any one of the parents.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Children Under Five

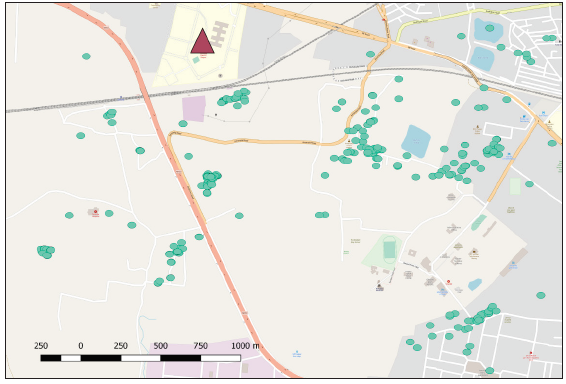

The final analysis included 353 children under five. Their informants were their mothers. Their households were within 5 km from the public tertiary care teaching hospital [Figure 1]. There were two government dispensaries in their locality. The surveyed population has a comparatively higher representation of female children (53.3%). About 93% of the surveyed population followed the Hindu religion. The mean age of under-five children surveyed was 3.1 years. Their demographic characteristics revealed that the majority of parents are 77.8% among mothers and more than 90% of the fathers are literate [Table 1]; 54.4% of the families were below the poverty line. Among the majority of the children, the age of the mother was more than 20 years (> 98%) [Table 1].

- Distribution of houses (green areas) with respect to the public multispecialty tertiary care hospital (triangle).

| Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender of the child under five | ||

| Male | 165 | 46.7 |

| Female | 188 | 53.3 |

| Education of the mother | ||

| Illiterate | 43 | 12.2 |

| Primary | 59 | 16.7 |

| Secondary | 88 | 24.9 |

| Matriculation | 119 | 33.7 |

| Graduate | 44 | 12.5 |

| Income of the mother | ||

| Earning | 72 | 20.4 |

| Not earning | 281 | 79.6 |

| Education of the father | ||

| Illiterate | 31 | 8.8 |

| Primary | 62 | 17.6 |

| Secondary | 95 | 26.9 |

| Matriculation | 120 | 34 |

| Graduate | 45 | 12.7 |

| Type of the family | ||

| Joint family | 180 | 51 |

| Nuclear | 173 | 49 |

| Birth order of the child | ||

| 1 | 147 | 41.6 |

| 2 | 140 | 39.7 |

| 3 | 51 | 14.4 |

| 4 | 9 | 2.5 |

| 5 | 6 | 1.7 |

| Religion | ||

| Hindu | 333 | 94.3 |

| Non-Hindu | 20 | |

| BPL card holder | ||

| No | 161 | 45.6 |

| Yes | 192 | 54.4 |

| Age of the mother | ||

| < 20 | 5 | 1.4 |

| 20–30 years | 295 | 83.6 |

| > 30 | 53 | 15 |

BPL: Below poverty line.

Types of Healthcare-Seeking of Children Under Five and the Associated Factors

Assessment of health-seeking decision-maker revealed that mothers were involved in the decision-making of healthcare-seeking for sick children under five among more than 89.9% of the families [Table 2]. The most common ailments among the children under five in the six months preceding the survey were cough and cold followed by fever. These were the conditions for which the parents approached a doctor or health professional for advice [Table 3]. The majority of the families (93.5%) approached private practitioners near their home for children under five ailments. Only 6.5% of the families approached government/public hospitals, including tertiary care hospitals nearby [Table 4]. There was no significant difference of visit to private or government healthcare facilities with respect to families possessing BPL cards (p value > 0.05). There was also no significant difference of hospital visit preference according to different families having different decision-makers (p value 0.285) [Table 5]. There was no significant difference of types of healthcare-seeking according to age, education, occupation, or type of the family of the mother (p value > 0.05 in each case). The birth order of the child and the education of the father also had no association with the type of hospitals they go to.

| Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Father | 25 | 7.1 |

| Mother | 187 | 53 |

| Both father and mother | 141 | 39.9 |

| Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Cough and cold | 265 | 75% |

| Pneumonia and breathing problem | 5 | 1.4% |

| Ear and skin problem | 6 | 1.6% |

| Accident | 3 | 0.84% |

| Fever | 216 | 61.1% |

| Any other (loss of appetite, failure to gain weight, developmental abnormality, and more | 64 | 18.13% |

| Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Private hospital or dispensary or clinic | 330 | 93.5 |

| Government doctor | 23 | 6.5 |

| First visit to private healthcare facility | First visit to government healthcare facility | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPL card | Yes | 151 (93.8%) | 10 (6.2%) | 0.83 |

| No | 179 (93.2%) | 13 (6.8%) | ||

| Decision-maker | Father | 22 (88%) | 3 (12%) | 0.285 |

| Mother | 178 (95.2%) | 9 (4.8%) | ||

| Both father and mother | 130 (92.2%) | 11 (7.8%) |

BPL: Below poverty line.

Geospatial Distribution of Health-Seeking with Respect to Tertiary Care Hospital

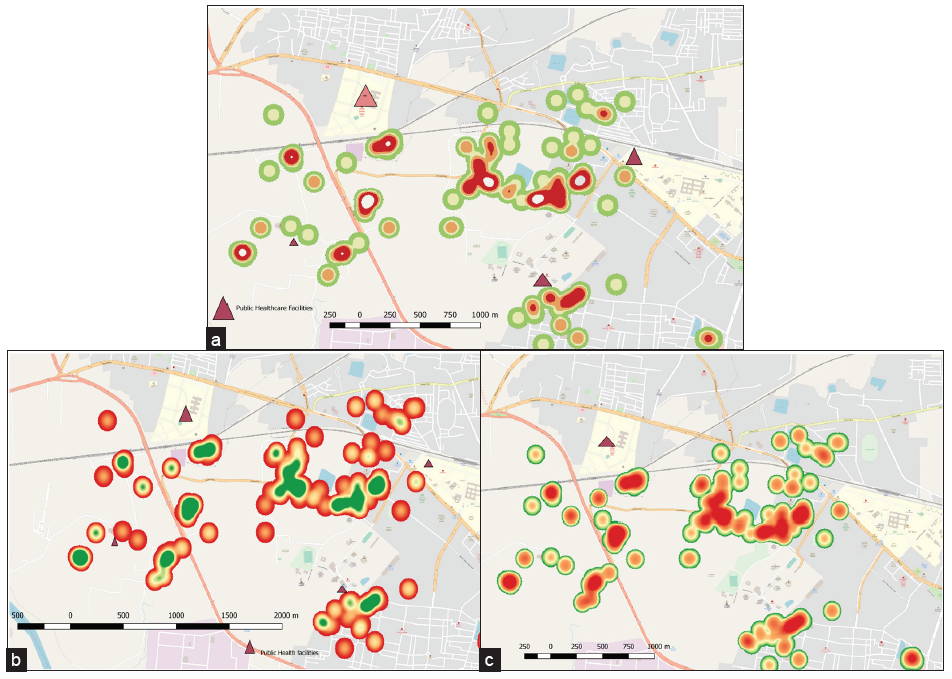

The geospatial distribution of the households belonging to children under five showed an even distribution within 3 km range from the government tertiary care multispecialty hospital [marked as triangle in Figure 1]. There were three other government dispensaries in the area [marked as triangles in Figure 2a]. The majority cases of children under five illness were fever cases [Figure 2a]. The distribution of fever cases, instances of decision-making by the mother, and healthcare-seeking in private hospitals were represented with heat maps to show the density of such cases with respect to the distance from government tertiary care hospitals and showed a similar pattern of distribution [Figures 2a-c].

- The heat maps showing spatial distribution of fever and cold cases among (a) children under five, (b) mothers as decisionmakers, and (c) private physician consultations. (a) Triangle: Public multispecialty hospital, Red area: Cluster houses with equal or more than two fever and cold cases, Green area: Houses without fever cases or less than two fever cases or without cold cases. (b) Triangle: Public multispecialty hospital, Red area: Cluster houses with mothers as decision makers, Green area: Houses with family members other than mothers as decision makers. (c) Triangle: Public multispecialty hospital, Red area: Cluster houses that consulted private healthcare facility, Green area: Houses that consulted public healthcare facilities.

DISCUSSION

This study was aimed to assess different types of healthcare-seeking and demographic factors associated with it among the mothers of children under five in an urban slum in the vicinity of a public multispecialty tertiary care teaching hospital and also to assess the geospatial distribution of the same. The place of survey was an urban slum, which has two public dispensaries and one newly built, fully functional public multispecialty tertiary care hospital within a 4 km radius [Figure 1]. This study was planned after eight years of the establishment of one of the premier, publically funded, tertiary care multispecialty teaching hospital, endowed with state-of-the-art healthcare facilities.

The majority of the surveyed children under five, who were sick in the preceding six months and for which healthcare was sought by the parents, was due to cough, cold, and fever. The trend of illness was similar across the country, as reported in several other studies across India.[7,19]

Among the entire 353 mothers of the children under five, 89.9% had contributed to the decision-making process during their children’s common ailments. Studies have shown that a mother’s input in decision-making improves the health-seeking.[20] In our study, we could not find any difference in seeking healthcare in private or public facility in spite of dominance in mother’s input. The majority of the family used to seek care from the private facilities (around 93.5%) irrespective of the mother’s decision-making power or socioeconomic class of the family [Table 5] [Figure 2]. The pattern of healthcare-seeking is similar to other parts of the country as concluded in studies by Tiwari et al., Yadav et al., Mishra et al., and Minhas et al., where the majority of community members were seeking care from the private healthcare facilities.[7–10] The newly founded public tertiary care hospital is not able to change the pattern of healthcare-seeking and associated financial burden even in the families below the poverty line in its vicinity, in spite of the availability of high-quality multispecialty care, at least for common childhood illnesses [Figure 2]. This is different from the findings of Fatma et al. in 2023, who reported that private facilities were preferred by the families from the high socioeconomic class.[21]

Many of the studies in various parts of the country showed a significant positive effect of maternal education, order of birth, socioeconomic class of the family, and the types of family in improving healthcare-seeking for common childhood illnesses.[4,7] But we could not find any associations of these factors in choosing private or public facilities.

The study has inherent limitations because of its design as a cross-sectional survey. We could not assess in detail the reasons for seeking care in private facilities or reason for not accessing care in a multispecialty public hospital because of resource constraint. There is a need for further qualitative and mixed method studies to assess various facets of this issue. The selection of a vulnerable population like the urban slum population in this study and the results suggest similar large population-based studies in other parts of the country before the conclusion being generalized in the country.

Recommendations

The majority of the caretakers or parents of children under five in the urban slum preferred a nearby private clinic or nursing home for seeking care for common childhood illnesses. Primary healthcare in urban areas needs renewed emphasis and political commitment for strengthening public dispensaries even after the establishment of public multispecialty tertiary care hospitals, which have mandates to provide advanced care and are not effective in changing care-seeking patterns and reducing simultaneous financial burden, for healthcare-seeking of the majority for childhood illnesses. There is also a need for improvement in the outreach healthcare by the multispecialty tertiary care hospital to improve the health status of the nearby population.

CONCLUSION AND GLOBAL HEALTH IMPLICATIONS

The commitment of policy-makers across the world under the aegis of the World Health Organization started with “Health for All by 2000” through a primary healthcare approach. The enthusiasm seemed to have fizzled away in recent times. Many of the developing nations are approaching universal health through a health insurance approach, which overemphasizes multispecialty hospitals rather than primary healthcare. This needs to be reassessed through the lens of the result of this study. There is a need to reemphasize the commitment toward primary healthcare as none is a replacement for the other.

Key Messages

-

About 93.5% of the families of an urban slum preferred consultation in private hospitals or private clinics as compared to nearby public multispecialty hospital.The decision to choose private service was very wide-ranging, irrespective of the socioeconomic status of the families and the education of the mother.

-

The spatial distribution of fever cases among preschool children, maternal decision-making, and private consultation show similar patterns with respect to the public multispecialty tertiary care hospital.

-

The establishment of government-funded multispecialty hospitals has not significantly changed the preference for private hospitals for children under five with common ailments, and quality primary healthcare through urban health centers and dispensaries in urban slums needs renewed policy-level commitment for improvement of care.

Acknowledgments

The community members and the mothers in the urban slum.

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Financial Disclosure

Nothing to declare.

Funding/Support

There was no funding for this study.

Ethics Approval

Institutional Ethics Committee, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Raipur, India approved the ethical clearance of the study. Approval number AIIMSRPR/IEC/2021/818, date 29/05/2021.

Declaration of Patient Consent

Patient’s consent not required as the patient’s identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Assisted Technology for Manuscript Preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of AI-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

None.

REFERENCES

- Health seeking behaviour in context. East Afr Med J. 2003;80(2):61-2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Factors influencing health-seeking behaviour among civil servants in Ibadan, Nigeria. Ann Ib Postgrad Med. 2018;16(1):52-60.

- [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Evolutionary concept analysis of health seeking behavior in nursing: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):523.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Factors associated with delay in treatment-seeking behaviour for fever cases among caregivers of under-five children in India: Evidence from the national family health survey-4, 2015–16. PLoS One. 2022;17(6):e0269844.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- [Accessed 2023 Mar 9,]. Available from: http://rchiips.org/nfhs/.

- Educational Level, Sex and Church Affiliation on Health Seeking Behaviour among Parishioners in Makurdi Metropolis of Benue State|Semantic Scholar. [Accessed 2023 Jan 3]. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Educational-Level%2C-Sex-and-Church-Affiliation-on-in-Ihaji-Gerald/ade91613c3a5918ae5a0ddc6647a4b351a1079d3.

- Health seeking behaviour and healthcare utilization in a rural cohort of North India. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10(5):757.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- A study on the health seeking behavior among caregivers of under-five children in an urban slum of Bhubaneswar, Odisha. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8(2):498-503.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Health care seeking behavior for common childhood illnesses in Birendranagar municipality, Surkhet, Nepal: 2018. PLoS One. 2022;17(3):e0264676.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Health care seeking behavior of parents of under five in District Kanga, Himachal Pradesh. Int J Community Med Pub Health. 2018;5(2):561-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Morbidity, Health-Seeking Behaviour and Out-of-Pocket Expenditure among Large Indian States|NITI Aayog. [Accessed 2023 Mar 9]. Available from: https://www.niti.gov.in/morbidity-health-seeking-behaviour-and-out-pocket-expenditure-among-large-indian-states.

- The long road to universal health coverage|NITI Aayog. [Accessed 2023 Mar 9]. Available from: https://www.niti.gov.in/long-road-universal-health-coverage.

- [Accessed 2023 Mar 9]. Available from: https://pmssy-mohfw.nic.in/index1.php?lang=1&level=1&sublinkid=81&lid=127.

- Union Minister for Health and Family Welfare, Dr. Mansukh Mandaviya asserts government’s commitment towards improving Access to Quality Education for the younger generation. [Accessed 2023 Jan 3]. https://pib.gov.in/pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1883704.

- Medical schools in India: Pattern of establishment and impact on public health – A geographic information system (GIS) based exploratory study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):755.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Epicollect5 – Free and easy-to-use mobile data-gathering platform. [Accessed 2024 Apr 18].Avaiibale from: https://five.epicollect.net/.

- Sample size determination in health studies: A practical manual. World Health Organization; 1991. [Accessed 2024 Apr 19]. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/40062

- QGIS project. [Accessed 2023 Mar 9]. Available from: https://www.qgis.org/en/site/.

- Health care seeking behaviour and out-of-pocket health expenditure for under-five illnesses in urban slums of Davangere, India. BMJ Global Health. 2016;1(Suppl 1) doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2016-EPHPabstracts.14

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Maternal decision-making input and health-seeking behaviors between pregnancy and the child’s second birthday: A cross-sectional study in Nepal. Matern Child Health J. 2020;24(9):1121-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Healthcare seeking behavior among patients visiting public primary and secondary healthcare facilities in an urban Indian district: A cross-sectional quantitative analysis. PLOS Global Public Health. 2023;3(9):e0001101.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]