Translate this page into:

House Ball Community Leaders’ Perceptions of HIV and HIV Vaccine Research

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background or Objectives:

Worldwide, men who have sex with men (MSM) and Transgender persons are vulnerable to psychosocial factors associated with high risk for HIV, and suffer disproportionately high rates of HIV/AIDS. In the United States (US), the House Ball Community (HBC) is a social network comprised predominantly of Black and Hispanic MSM and Transgender persons who reside in communal settings. This study explores Western New York HBC leaders’ perceptions of HIV in their communities and their knowledge of HIV prevention strategies, including HIV vaccine trials.

Methods:

The project was conducted using an exploratory approach based on the principles of Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) methods. An HIV behavioral risk assessment provided descriptive data, while qualitative measures explored psychosocial and behavioral factors.

Results:

Behavioral assessments indicated high levels of risky sexual behaviors and experiences of violence. Interviews with 14 HBC leaders revealed that knowledge of HIV and local HIV vaccines trials was limited. Barriers to HIV knowledge included fear of peer judgment, having inaccurate information, and lack of formal education. Experiencing violence was identified as barrier to positive health behavior. Nevertheless, the HBC was described as a safe and creative space for marginalized MSM and Transgender youth.

Conclusion and Global Health Implications:

Findings suggest that the interrelation between health problems and social context amplify HIV risk in the HBC. The organizational structure and resources of the HBC, and MSM/Transgender communities worldwide can be instrumental in informing interventions to address HIV-related risk behaviors and create appropriate recruitment tools to ensure their representation in HIV research.

Keywords

LGBT

HIV

MSM

Transgender populations

MSM/Transgender psychosocial

HIV risk factors

HIV and black/Latino MSM

Syndemic factors

MSM/Transgender communities

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) describes HIV among men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender persons as the “invisible epidemic,” bringing to the forefront the vulnerability of these populations and the need for targeted interventions.1 MSM and Transgender men and women (TGM, TGF) face significant social and sexual health disparities, which include disproportionately high rates of HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infections (STIs).2,3

1.1. Background of the Study

In the United States (US), in 2016, MSM accounted for 67% of all new HIV infections, and young MSM (aged 13-34 years) accounted for 64% of HIV diagnosis.4 The rates were highest among young Black/African American MSM ages 13 to 24 years, who accounted for an estimated 36% of new HIV infections in the MSM population followed by young Latinos/Hispanics MSM who accounted for 23%, compared with 15% of White MSM of the same age range. In 2019, newly identified HIV infection is estimated at 14% among Transgender persons, with 84% being Transgender women.5 Similarly, among Transgender women, the highest proportions of newly identified HIV infection were among Blacks/African Americans (44%), compared with Hispanics (26%) and White (7%) Transgender women.

Such disparities are fueled by factors including marginalization, loss of family, homophobia, and “sexual minority stress” (prejudice and stigma that combine to negatively impact a person’s mental and emotional health). These factors often result in increased risky sexual behavior, sexual abuse, verbal harassment, intimate partner violence (IPV), and pressures of gender conforming identity.3,6,7 Additional HIV-related social risk factors in this population include increased likelihood of homelessness, commercial sex work and drug use.2,3,6,7 While MSM and Transgender people are at increased risk for HIV and related cofactors, these communities have also developed protective behaviors including resilience and building strong social networks.

One such respite from the multitude of social problems is the development of strong social support through the House Ball Community (HBC), comprised predominately of MSM and Transgender people of color.3,8 The HBC is a sub-culture of the LGBT community in which individuals are organized into social groups referred to as ‘Houses’ that actively compete against each other in social events known as ‘Balls’(Ballroom).9-12 The social “Houses” are similar to a nuclear family, with a ‘Mother’ and/or a ‘Father’ role typically assumed by a TGF or MSM who oversees the ‘kids’ or ‘children’ (young house members usually between the ages of 14 and 24).

1.2. Objectives of the Study

In light of disproportionally higher rates of HIV incidence among MSM and Transgender communities of color (Latino and Black/African American), the HBC leadership (i.e., House “Mother” and “Fathers”) presents an important avenue for increasing awareness of HIV prevention strategies, including the need for participation in HIV vaccine trials in the US. This study explores efforts by the Western New York HBC leaders to address HIV and social problems in their Houses, their knowledge of HIV prevention behavioral strategies and their awareness of and attitude toward HIV vaccine trials.

2. Methods

The study used an exploratory approach based on the principles of Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) methods.13 Qualitative and quantitative measures were utilized to explore psychosocial and behavioral factors related to HIV/AIDS and HIV vaccine research awareness among HBC leaders in Western New York in order to inform future interventions and recruitment efforts.

2.1. Community Participation and Collaboration

The HIV Vaccine Trials Network’s Clinical Research Site at the University of Rochester (UR) is known locally as the Rochester Victory Alliance (RVA). RVA works closely with community organizations to facilitate the recruitment of individuals who are at low/no risk for acquisition of HIV infection into early phase preventive HIV vaccine trials, as well as individuals who are at higher risk for HIV acquisition for advanced phase studies. RVA has a history of collaboration with the Men of Color for HIV/AIDS (MOCHA) Center and the HBC through the previous establishment of the Council of Houses (COH). MOCHA is a community-based organization that specifically addresses HIV/AIDS health concerns affecting gay men including providing information, services, advocacy and more. The COH, composed of members of the RVA, MOCHA and House Ball leaders, designed and implemented the project described here.

2.2. Data Collection

Pilot data reported was collected between March 2009 and May 2011, consisting of qualitative individual interviews, a focus group, and a Demographic and Behavioral Questionnaire completed by 14 leaders and prominent members of 7 of the existing 12 House Ball Communities in the Rochester/Buffalo region of New York. Of the 14 who completed the survey, 7 participated in individual interviews, and 7 in the focus group. All informants were over 18 years old and leaders of a “House.” They had attended at least two “Balls” and participated as contestants in at least one “Ball.” They self-identified as African-American, Latino, Afro-Latino or Afro-Caribbean, MSM or TGF.

We utilized a directed purposeful and snowballing sampling strategy.14 The core group of informants were from the COH, who then referred other ‘Mothers’ and ‘Fathers’ as well as leaders from the local houses. Participants involved in the individual face-to-face interviews received a $30 gift card. Individuals participating in the focus group received a $20 gift card, refreshments and bus passes.

2.3. Interviews

A focus group was conducted with 7 leaders of the local Houses to identify HIV knowledge and awareness as well as educational needs of the HBC. Individual in-depth interviews were then conducted with 7 other leaders and prominent members of the HBC, some of whom were members of the COH. The focus group was conducted at MOCHA offices, while the individual interviews were held at private offices either at MOCHA or at the UR. Interviews were conducted by trained researchers who were also members of the COH. The focus group lasted approximately 60 minutes while the individual interviews lasted between 45 and 60 minutes. Following verbal informed consent, interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed.

All project participants (N=14) were asked to complete a Demographic and Behavioral Questionnaire to provide additional information on sexual behavior and other factors associated with HIV risk.

2.4. Instruments

i. Semi-structured Interview Guide

The interviews (individual and focus group) were conducted using a semi-structured guide. The guide was developed to capture the psychosocial, behavioral and knowledge issues related to HIV/AIDS prevention and HIV vaccine trials. Individual and group interviews began with open-ended questions about the participant as a means to get to know the interviewee. The guide then led to the exploration of subjects’ experience as HBC members. There was an emphasis on questions about the impact of HIV/AIDS on the HBC. The facets of the HBC that make it a unique population were also discussed. Each participant was also given the opportunity to talk about other pertinent topics. Field notes and analytic memos were taken by the interviewers before, during, and after the interview. In keeping with grounded theory methodology, the guide was revised as the analysis of study data progressed.

ii. Demographics and Behavior Questionnaire (DBQ)

The DBQ is part of the Behavioral Risk Assessment (BRA) for HIV vaccine studies from Clinical Trials Units across the U.S. The BRA was developed and tested specifically for HVTN sites and served as a tool for collecting individual-level data from project participants.15 The DBQ was administered prior to conducting interviews. The DBQ collected demographic data (age, sex at birth and current gender identity, religion/spiritual beliefs, marital/partnership status, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, education, income, employment), and assessed knowledge related to HIV risk, attitudes about HIV, relationships, condom use, sexual behaviors, drug use, mental health, and attitudes related to HIV vaccine research.

2.5. Analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted on data from the DBQ completed by the 14 participating leaders. Interview data were analyzed from transcripts of audio recordings, using content and thematic analysis methods, both widely used in qualitative data analyses.16 Researchers summarized the results and reported to members of the COH for their input in examining and interpreting findings. Content analysis identified factual data about the HBC in Western New York, as well as knowledge, awareness and beliefs about HIV prevention and vaccine trials, while thematic analysis enabled the extraction of general themes regarding HIV in the HBC. Coding and analysis was conducted by trained investigators who met regularly to discuss findings. Members of COH were asked for their input on result interpretation. In addition to the project-specific questions, additional themes identified were violence, sexually transmitted diseases, intimate partner violence, childhood sexual abuse, drug/alcohol use, depression/suicide, and commercial sex work.

2.6. Ethical Approval

This study was conducted with approval from the University of Rochester Medical Center Research Subject Review Board (RSRB # 27446).

3. Results

The House Ball Leaders (N=14) raised several psychosocial issues within the HBC in general, aspects of HIV knowledge, and HIV vaccine awareness and participation in clinical trials. The participants explained beliefs within the HBC and their efforts to address these risky behaviors.

3.1. Sociodemographic Characterisitcs

The 14 participating leaders were all born male, with 2 self-identifying as Transgender women. Most were African American (n=11) with a mean age of 25.4 years, homosexual (n= 9), and single (n=9). More than half (n=9) reported some college or a college degree and were employed. Several participants reported having been arrested (n=6) and/or convicted of a crime (n=3) at some point (Table 1).

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age* (years) | 25.35 |

| Race | |

| Black/African American | 11 (78.6) |

| Hispanic | 4 (28.6) |

| Gender Identity | |

| Male | 10 (71.4) |

| Transgender male | 2 (14.3) |

| Transgender female | 2 (14.3) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Heterosexual | 2 (14.3) |

| Bisexual | 2 (14.3) |

| Homosexual | 9 (64.3) |

| Other | 1 (7.1) |

| Relationship status | |

| Single | 9 (64.3) |

| Separated | 1 (7.1) |

| Partnered/Significant other | 4 (28.6) |

| Education level | |

| Less than high school | 1 (7.1) |

| High school/GED | 4 (28.6) |

| Some college | 5 (35.7) |

| College or higher | 4 (28.6) |

| Currently employed | 8 (57.1) |

| Income ≤ $50,000 | 14 (100) |

The mean age for initiation of sexual activity was 13.7 years (range: 8-18 years). Half of the participants reported currently having a primary male lover, and an average of 6.1 male lovers, but no female lovers. Only half of the participants (n=7) shared that they were aware of the HIV status of all their partners. Few participants reported always using a condom while performing (n=3) or receiving (n=2) oral sex, and when topping (insertive) (n=4) or bottoming (receptive) (n=5) during anal sex. (Table 2) The majority of the participants reported not engaging in vaginal sex (n=10). Several participants (n=5) reported having had at least one sexually transmitted disease (Table 2).

| Sexual Behavioral History | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age of sexual debut (years)* | 13.7 |

| Gender of first sexual partner | |

| Male | 10 (71.4) |

| Female | 2 (14.3) |

| No response/Other | 2 (14.3) |

| Has a primary male lover | 7 (50.0) |

| Number of male sex partners* | 6.1 |

| Number of female sex partners* | 0 |

| Exchanged sex for benefits (money, drugs, shelter/housing, other) | 9 (64.3) |

| Forced to have sex | 6 (42.9) |

| Age of forced sex* | 14.8 |

| Told someone about the forced sex | 3 (21.4) |

| Highest risk sexual behavior | |

| Receptive anal sex without condom | 5 (35.7) |

| Insertive anal sex without a condom | 4 (28.6) |

| Giving oral sex without a condom | 2 (14.3) |

| None | 2 (14.3) |

| Know HIV status of all partners | 7 (50.0) |

| Asked all sex partners their HIV status | 8 (57.1) |

| Has had a sexually transmitted infection | 5 (35.7) |

| Degree of perceived risk of HIV** | 2.1 |

| Mental health and drug use | N (%) |

| Taken medication for mood, emotions, or nerves | 2 (14.3) |

| Feelings of hopelessness | 8 (57.1) |

| Number of times feeling hopeless in the past 12 months* | 4.6 |

| Considered suicide | 5 (35.7) |

| Number of times considering committing suicide in the past 12 months* | 2.2 |

| Currently smoke cigarettes | 1 (7.1) |

| Any previous drug use | 12 (85.7) |

| Has sex after using alcohol or drugs | 9 (64.3) |

3.2. Psychosocial Behaviors

Participants discussed several psychosocial behaviors: witnessing/experiencing violence, including IPV, STDs, childhood sexual abuse, drug/alcohol use, commercial sex work, and depression/suicide.

Intimate partner violence was as a sensitive topic for participants to discuss with members of their houses. The leaders described several techniques used to attempt to make their ‘kids’ aware of the unhealthy relationships they were in. These methods included using movies, and one-on-one discussions. One leader iterated the effectiveness of using movies: You make it a movie night. You have to visually trick them into seeing it… When they start talking…you’re there!”

The participants also identified drug and alcohol abuse as prevalent issues. “There’s a big flux of drug usage in the Ballroom scene… Drug use is just really big and with drug usage you get the risky behaviors and the sexual acts that can lead to HIV.”

Though some participants faced their own issues with drugs and alcohol; they discussed their focus on providing the ‘children’ with alternative outlets, explaining the negative effects of substance abuse, encouraging them to resist peer pressure to do drugs, and educating them about the consequences of these behaviors.

Participants recognized that some house members participated in sex work or were thinking about it for economic reasons, the notion of “fast money” for various personal and occasional needs (e.g., clothes, drugs, expenses related to House Balls). Participants explained their obligations to focus on educating the ‘children’ on how the commercial sex industry works, alternatives, and the need for protection if they decided to proceed with the profession.

Another topic raised was mental health, specifically depression and suicidal ideation. When faced with members suffering from depression, House leaders described attempting to get the individual to open up about what was troubling them, and trying to get their mind off that topic.

3.3. HIV Knowledge, Attitudes, Beliefs, and Prevention Efforts in the House Ball Community

When asked about the community’s awareness of HIV transmission, unprotected sex and the use of drugs and alcohol prior to sexual activity were identified as the main routes of transmission. Swallowing during oral sex was also mistakenly believed to protect against HIV and other STIs. Several participants recounted several popular beliefs that: HIV was currently no worse than diabetes, that those who are infected often appear sickly, and that in some cases, members purposely attempt to infect others.

3.4. HIV Educational Activities within the House Ball Community

Participants were very much aware of the need for increased awareness of HIV in their houses. Several reported conducting many activities to educate their members. The participants spoke of the effectiveness of outreach organizations such as MOCHA to help facilitate workshops that help provide accurate information about HIV. They also mentioned addressing HIV during their house meetings in the form of discussions or storytelling. Some participants stated that since HIV is such a sensitive topic, they often addressed it by having one-on-one discussions. One participant suggested the use of “eye candy,” which would consist of a HIV-infected individual who is very attractive to illustrate that healthy, attractive people can be HIV- infected.

3.5. HIV Vaccine Trial Knowledge

Participants’ knowledge of vaccines in general, HIV vaccine research, and related clinical trials was limited. They defined a vaccine as “something that either cures something… a disease or something… or it just keeps it down to a minimum effect where it can’t hurt the person.” However, a few were able to define it as “a dead cell version of a virus… so your body can make antibodies.” Although participants were not well informed about HIV vaccine trials, they were well aware of the importance of developing a HIV vaccine because “HIV is killing a lot.”

3.6. Challenges and Barriers to Promoting Positive Health Behaviors

Participants interviewed identified challenges they faced in the HBC. An important barrier was the reluctance to discuss certain topics such as violence. Perpetrators often did not want to discuss the issue because it was their way of appearing tough; victims did not want to recognize it because they were embarrassed, or because they did not want to acknowledge that it was occurring. These challenges were similar in reported cases of intimate partner violence.

The participants also identified challenges related to health education and getting ‘kids’ to reduce their high-risk behaviors. The issues include leaders and other community members spreading myths or incorrect information, ‘kids’ not willing to listen to their house ‘parents’, ‘kids’ thinking these risk factors are normal, and house ‘parents’/leaders not being comfortable talking about certain subjects such as sexual activity or sexually transmitted diseases.

4. Discussion

This study provides important information about minority MSM and Transgender communities, which both face disproportionately high rates of HIV/STI infection, substance abuse, mental illness, stigma and marginalization, and have been underrepresented in HIV vaccine efficacy trials among high-risk populations.17-19 Despite the support garnered within the community, the study reveals that members are still plagued by a range of psychosocial issues associated with being marginalized by mainstream society, having limited access to culturally tailored and/or relevant health education, and limited financial stability. Such marginalization can engender feelings of loneliness, depression, anger, anxiety, and other adverse health outcomes in ethnic minority gay men.20,21 The HBC leaders interviewed in this study are aware of this problem among their member ‘children’ and try to inform and warn them of the dangers and consequences of such behaviors.

4.1. Discussion

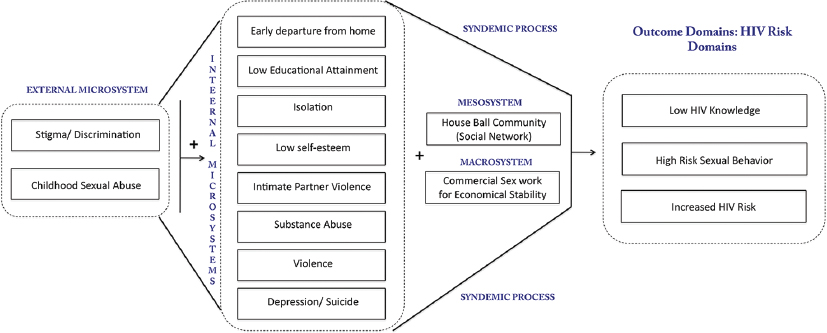

The qualitative findings support the interrelations between the emergent themes of substance abuse, IPV, and risky sexual behaviors, which fuel HIV risk.21,22 These interrelations support the theory of syndemics, which postulates that the social and biological epidemics are not singular. Instead, they work together in a synergistic, reinforcing fashion to form a syndemic system which increases the HIV/STI vulnerability and adversely affects the health of MSM and Transgender people.3,23,24 This concept is exemplified by the HBC examined in this study (Figure 1), in which the individual is exposed to a stigma and discrimination, and in some cases childhood sexual abuse. This environmental backdrop is beyond the control of the individual. However, the setting influences individual choices such as leaving home at an early age, and the creation of an internal microsystem that can favor adverse self-regulating behaviors and thoughts such as low self-esteem, intimate partner violence, substance abuse and depression. For survival, the HBC is sought out as a communal support system and an environment of understanding. Set apart from mainstream society but still a functioning community, the HBC becomes a mesosystem in which the individual can operate and connect with others with similar identities and challenges, forming a sustainable social network.

- Syndemic process of influential systems that create an environment for increased HIV risk in members of the HBC

Macrosystems such as opportunities for employment and educational attainment also influence the individual’s choices. In this case, our study was able to identify that limited educational opportunities, or being rejected from traditional occupations due to appearance, may force individuals in this network to resort to commercial sex work. The syndemic lens emphasizes the interrelation of these common psychosocial health problems and sexual minority stress working in concert to increase HIV risk.23-25 Parsons et al., found that MSM with 3 to 5 syndemic issues (Polysubstance abuse, Depression, Childhood Sexual Abuse, Partner Violence, and Sexual Compulsivity) were 25.4% and 27.3% more likely to be HIV infected and engage in high risk sexual activity, respectively.26 Brennan et al. found that Transgender individuals with 3 or 4 syndemic issues were 6.61 times as likely to HIV infected and 4.53 times as likely to engage in unprotected anal intercourse.6

Alongside these syndemic conditions co-exists a system of social support in the HBC that proves important in increasing members’ self-confidence and validation, which in turn helps to counter the negative effects of the many stressors and psychosocial factors they experience.3,27 The social support received in the HBC may work to counter the deleterious effects of the multifaceted stressors and psychosocial factor faced by this community by increasing “self-confidence and validation.”3,27 This positive aspect and strength of the HBC can be exploited to the betterment of the community by equipping their leadership with adequate information and tools for addressing HIV in their respective Houses.

4.2. Limitations

An important limitation of this study is the small sample size. However, this study targeted leaders of half of the Houses in the region and sought to provide depth of data rather than breadth, since this is among the few studies addressing marginalized populations of YMSM of color belonging to the HBC.24,25

5. Conclusion and Global Health Implications

Globally, MSM and Transgender populations experience similar psychosocial ills resulting from discriminatory cultural, religious and legal norms and regulations.28,29 Findings from this study suggest that the interrelation between health problems and social context amplify HIV/STI risk among such populations.22,30 Framed in the context of the theory of syndemics, these findings underline the importance of understanding the challenges as well as the resiliency factors in order to shape culturally relevant interventions among MSM and Transgender populations. Further, promoting collaboration among clinicians, researchers and the MSM and Transgender communities is essential to the success of HIV preventive efforts.29,31 Interventions should allow the knowledge, resiliency, and social support within the MSM and Transgender communities to drive program development and social marketing campaigns aimed at increasing their participation in HIV prevention efforts.23,25,31

Acknowledgements:

We are grateful to the leaders of the House Ball Community in Western New York who participated in these interviews. Many thanks to Catherine Bunce, Cindi Lewis and Heather Elder from the University of Rochester for their assistance with outreach and data management.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Funding/Support: This study was supported in part by the: 1) University of Rochester HIV/AIDS Clinical Trials Unit grant UM1-AI069511 from the National Institutes of Health, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. 2) HIV Vaccine Trials Network, Legacy Project, Vaccine and Infectious Disease Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA. Support for the HVTN comes from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), an agency of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). 3) University of Rochester Developmental Center for AIDS Research Grant P30 AI078498 (NIH/NIAID). 4) University of Rochester CTSA award number TL1 TR000096 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health.

Ethics Approval: The University of Rochester Medical Center Research Subject Review Board approved this study (RSRB # 27446).

References

- World Health Organization A Hidden Epidemic:HIV, Men Who Have Sex with Men and Transgender People in Eastern Europe and Central Asia Regional Consultation 2010. rhttp://www.euro.who.int/data/assets/pdf_file/0010/140410/e94967.pdf

- Girlfriends:evaluation of an HIV-risk reduction intervention for adult transgender women AIDS education and prevention:official publication of the International Society for AIDS Education. Oct. 2011;23(5):469-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- ''It's Like Our Own Little World'':Resilience as a Factor in Participating in the Ballroom Community Subculture. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(4):1524-39.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2016. Centers for Disease Control HIV and Gay and Bisexual Men. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/msm/index.html

- 2019. Centers for Disease Control HIV and Transgender People. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/transgender/index.html

- Interventions AMTNfHA Syndemic Theory and HIV-Related Risk Among Young Transgender Women:The Role of Multiple, Co-Occurring Health Problems and Social Marginalization. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(9):1751-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations:conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin Sep. 2003;129(5):674-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk behaviors and psychosocial stressors in the New York City house ball community:a comparison of men and transgender women who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior Apr. 2010;14(2):351-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- HIV prevalence and associated risk behaviors in New York City's house ball community. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(6):1074-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Statewide Estimation of Racial/Ethnic Populations of Men Who Have Sex with Men in the U.S. Public Health Reports. 2011;126:60-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Constructing Home and Family:How the Ballroom Community Supports African American GLBTQ Youth in the Face of HIV/AIDS. J ournal of Gay &Lesbian Social Services. 2009;21:171-88.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reconciling Reality With Fantasy:Exploration of the Sociocultural Factors Influencing HIV Transmission Among Black Young Men Who Have Sex With Men (BYMSM) Within the House Ball Community:A Chicago Study. J ournal of Gay &Lesbian Social Services. ;27(1):64-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promotion Practice. 2006;7(3):312-323.

- [Google Scholar]

- Qualitative Research Methods (4 th edition). Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2013.

- Behavioral risk assessment in HIV Vaccine Trials Network (HVTN) clinical trials:A qualitative study exploring HVTN staff perspectives. Vaccine. 2013;31(40):4398-405.

- [Google Scholar]

- Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis:A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2006;5(1):80-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Racial differences in factors that influence the willingness to participate in medical research studies. Annals of Epidemiology. 2002;12(4):248-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Global HIV Epidemics among Men Who Have Sex with Men. Washington DC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 2011.

- Virology Moving forward in HIV vaccine development. Science. 2009;326(5957):1196-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- HIV prevention for black men who have sex with men in the United States American Journal of Public Health . J un. 2009;99(6):976-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(6):939-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Operating without a safety net:gay male adolescents and emerging adults'experiences of marginalization and migration, and implications for theory of syndemic production of health disparities. Health Education &Behavior :the official publication of the Society for Public Health Education. 2011;38(4):367-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Syndemic processes among young men who have sex with men (MSM):Pathways toward risk and resilience [Doctoral]:Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburg 2011

- A Longitudinal Investigation of Syndemic Conditions among Young Gay, Bisexual, and Other MSM:The P18 Cohort Study. AIDS and Behavior. 2015;19(6):970-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- HIV in transgender communities:syndemic dynamics and a need for multicomponent interventions. J ournal of AIDS. 2010;55(Suppl 2):S91-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of Day-Level Sexual Risk for Young Gay and Bisexual Men. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(4):1465-77.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development, risk, and resilience of transgender youth. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2010;21(3):192-206.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transgender in Africa:invisible, inaccessible, or ignored? SAHARA Journal. 2012;9(3):160-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Global health burden and needs of transgender populations:a review. Lancet. 2016;388(10042):412-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Race and sexual identity:perceptions about medical culture and healthcare among Black men who have sex with men. J ournal of the National Medical Association. 2004;96(1):97-107.

- [Google Scholar]

- An HIV intervention tailored for black young men who have sex with men in the House Ball Community. AIDS Care. 2015;27(3):355-62.

- [Google Scholar]