Translate this page into:

Clients’ Perspectives on Quality of Delivery Services in a Rural Setting in Tanzania: Findings from a Qualitative Action-Oriented Research

*Corresponding author email: geraldmakuka@gmail.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Objective:

To know and understand the perspectives of women on the quality of maternal health services provided at their health facility (HF) and to incite community self-propelled problem identification and way forward.

Methods:

A qualitative action- oriented research was conducted in a rural setting in Tanzania from 2011 to 2014. Twenty In-Depth Interviews (IDIs) and two Focus Group Discussions were held. The IDIs were conducted with mothers who had attended antenatal care at the HF and delivered there. The recordings transformed into English texts were used for analysis to get themes and possible explanations that were compared and reflected.

Results:

More than half 60% of the respondents reported to have experienced abuse by the health staff, 80% reported lack of amenities and all agreed to unavailability of health services at odd hours or weekends.

Conclusion and Global Health Implications:

This study reveals that the quality of maternal health services provided at the HF is not up to standard. The study demonstrates the importance of self-diagnosis in a community and to propel self-community interventions towards improving rural health services. The government, researchers and other stakeholders have key roles in the elimination of health disparities and unhealthy political mingling in health care.

Keywords

Quality

Maternal Health

Qualitative

Action-Oriented Research

Rural Setting

Tanzania

1. Introduction

Despite high impact interventions in Sub-Saharan Africa, more effort is required to achieve the Millennium Development Goals four and five.[1] Assisted deliveries by skilled birth attendants are pivotal in reducing maternal morbidity and mortality.[1,2] In 2012, maternal mortality rate in Tanzania was estimated at 420/100,000 live births.[3] The 2010 District Health Survey revealed that, 96% of pregnant women attended antenatal clinic at least once in their gestational period while 43% of them attained the recommended four visits. Only 31% attended postnatal care. The survey further revealed a dismal 51% institutional delivery.[4]

Dispensary is the basic unit in the Tanzania health system tasked with the delivery of primary health care (PHC) at grassroots level. There is a minimum staffing at dispensary level. This includes one Clinical Officer (CO)/clinical assistant, a nurse, pharmaceutical assistant, Reproductive and Child Health (RCH) care nurse, two nurses for delivery, a laboratory assistant, a medical attendant, community health worker, a security guard, and administration officers.[5] The health center (HC) is the second PHC facility.[6] HCs are staffed with a minimum of one medical doctor, one Assistant Medical Officer (AMO), two COs, two midwives, one assistant nursing officer, nine nurses, one radiographer technologist, one health laboratory technologist, one laboratory assistant technologist, one pharmaceutical technologist, community health worker, assistant environmental health officer, ophthalmic nursing officer, optometrist, mortuary attendant, two security guards, four administration officers, six medical attendants, two cleaners, one electrician/maintenance staff, and one driver where transportation services are available.[5,7] According to the national referral system, the first and second level health facilities (HF) refer to a District or Regional hospital and rarely to specialized hospitals.

World Health Organisation defines quality of care as the extent to which health care services provided to individuals and patient populations improve desired health outcomes. Quality of care during childbirth in health facilities reflects the available physical infrastructure, supplies, management, and human resources with the knowledge, skills and capacity to deal with pregnancy and childbirth.[8] Customer satisfaction is a meaningful and important indicator of quality service delivery. Inquiring from customers what they think about the services they receive is an important step towards improving the quality of care. Therefore, it is important to measure the quality of health services delivery through client satisfaction, as satisfaction is one of the meaningful indicators of patient experience of health care services. Asking patients what they think about the care and treatment they have received is an important step towards improving the quality of care, and to ensuring that local health services are meeting patients’ needs.[9] The assessment of quality is a learning platform in deciding which aspects of care need to be improved.[10]

Although the National Health Policy requires PHC facilities to be adequately staffed and equipped, the majority of them are understaffed and ill-equipped leading to customer dissatisfaction.[11] A number of studies on quality of maternal services by measuring clients’ perspective have been conducted in Tanzania with majority of them being observational or by use of questionnaire. Studies in Uganda and India have shown the direct relationship between the facility’s physical status and customer attraction for attendance.[12,13] Similar studies in Tanzania showed a direct relationship between service provider attitude and customer attendance at the health facility coupled with drugs and medical equipment availability.[14]

Few studies used Action Research (AR) to understand community and health worker challenges associated with delivery of quality care at PHC facilities. AR focuses on bringing change when the researcher and researched learn from one another. The research participants would contribute actively to offer solutions to the health problem affecting them.[15] It serves as an excellent way of learning health disparities affecting a population such as inaccessibility to quality health care and how to ameliorate them.[16]

The medical curriculum at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College (KCMUCo) involves 20% of the time devoted to Community Health during the first two years of medical school. Each student group is allocated a village for two years as part of learning about community diagnoses. It was during this time that the students heard of the villagers’ complaints about poor quality of services at the HF. The community in good faith asked the medical students allocated in their village to help them find a solution to their ongoing problem.

This research assessed clients’ perspectives on quality of maternal health services delivered by the health service providers. It further sought to help the community in improving maternal health services delivery in their setting. Lessons learnt will assist policy-makers, government and private actors especially our institution and other organizations on how and where to improve maternal health services.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

A qualitative “Action Oriented Research” was conducted from 2011 to 2014.

2.2. Study setting

The study was conducted in Kivulini community village of Kileo ward in Mwanga District, Kilimanjaro Region. The setting is 40 km from KCMUCo. The Kileo HF serves two villages namely Kivulini with 2,520 population and Kileo with 4,255 population. Kivulini village is approximately two kilometers from the HF. The HF provides RCH services including delivery. In 2014, the HF had a total of seven health workers (HWs) namely the CO (leader), four Medical Attendants and two Maternal and Child Health Aides responsible for RCH services.

2.3. Study population

The study population was women who had delivered at the HF between 2011 and 2014 and who were Kivulini residents.

2.4. Sample population

A total of 20 women were interviewed during the study. The number of women participants to be interviewed for the study was based on saturation of the themes. We stopped at a certain number of interviews once the results were similar with no new input. All of the twenty women participants that were approached accepted to partake in the study.

2.5. Data collection methods

In-depth interview (IDI) was used. RCH records were used to select participants and a trusted village link-person identified the women. The purpose of the interview was explained and all participants were assured of confidentiality, safety and dignity with omission of identities and names. Thereafter, an ideal time, date and place of interview was arranged. Individual IDIs were then held. A total of twenty IDIs were conducted. Probing questions were used for a better understanding where necessary. LePSA technique was also used during the Focus Group Discussions (FGD). LePSA is Learning centered Problem Solving Self-discovery Action Oriented, a guided learning process that is preceded by a role-play or a story.

2.6. Focus group discussions

After the interviews, FGD was done using themes that emerged from IDIs. 2 FGDs were held, each 2 hours. The first was done in Kivulini village with a group consisting of the HWs, village government, primary teachers, KCMUCo representative and women representatives at the village office. The other was done in the neighbouring village with the village council and Village Executive Officer (VEO). One researcher asked the questions in Swahili and recorded using a voice recorder whilst another wrote down in English what was said by the participants. The FGD was carried out with the assistance of LePSA method.

2.7. Intervention used to help address the problem and identify the context

LePSA session was used to address the problem. LePSA focuses the participants on the discussion at hand and builds interest towards the problem and clarifies misconceptualization. The members themselves explain the starter theme and reflect if it was taking place within their setting. Participants give the solution to the problem but the facilitator is there to make the discussion proceed well. LePSA ensures a non-dictating learning process where members targeted in the discussion are involved in the problem solving and learning. The research team was able to have in-depth understanding of the context from the participants view.

2.8. Data analysis

The data was analysed using thematic framework analysis. The recordings were transcribed and transformed into English texts that were used for analysis. Findings were interpreted to get themes and possible explanations and compared and reflected to previous data on customer care.

2.9. Ethical clearance

Ethical clearance to do the study was obtained from Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center (KCMC) ethical clearance committee. Permission and consent was sought from the village authority and individual participants beforehand.

3. Results

3.1. Selected sociodemographic characteristics of study respondents

Out of 20 of the respondents, the age group 21-25 constituted the majority (40%) of the respondents, with the overall respondents means average age of 27.4. Only one woman had a para of above 4. Majority of the women were married (85%), belonging to the native Pare tribe and Christian religion. All women (100%) have only reached up to primary education with none having secondary or tertiary education level. Majority of the women are peasants with those who are self-employed largely doing petty businesses such as selling vegetables, fruits amongst others in the market place (Table 1).

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 21-25 | 8 (40) |

| 26-30 | 6 (30) |

| 31-35 | 6 (30) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | - |

| Married | 17 (85) |

| Cohabiting | 3 (15) |

| Parity | |

| 1-3 | 15 (75) |

| 4+ | 5 (25) |

| Religion | |

| Muslim | 9 (45) |

| Christianity | 11 (55) |

| Tribe | |

| Mpare | 16 (80) |

| Mchaga | 3 (15) |

| Others | 1 (5) |

| Education | |

| Less than elementary 1 | - |

| Elementary 2-6 | 1 (5) |

| Elementary 7+ | 19 (95) |

| Occupation | |

| Unemployed | - |

| Peasant | 17 (85) |

| Self-employed | 3 (15) |

3.2. Poor attitude of the health workers

In all, 12 out of 20 of the women (60%) reported to have been abused and mistreated by the facility staff. There were several shocking narrations from several participants. One customer cited the following scenario:

‘The maternal services are still very bad at our healthy facility especially if you go there at night. I went to the facility for my sixth delivery at 11pm and was answered badly and shouted at with my husband She then went to sleep soon after opening for us and instructed us to wake her up when I am close to delivery. My husband went to look for a female neighbor to be with me. She was wakened up when my labour pains intensified and assisted me to deliver’, WM 1.

‘When I went to deliver, the health worker on duty left me alone saying that it was her prayer time. I was treated harshly during the whole process of delivery and soon after delivery, the nurse instructed me to mop the blood off the floor with my own kitenge (local dress)’, WM 4.

3.3. No physical or staff upgrade to a HC level

The findings revealed that although the HF is recognized as a HC, the facility infrastructure and staffing level did not match its hierarchy. More than two thirds (16/20) of the respondents (80%) complained of lack of amenities like drugs, medical equipment, beddings and poor health laboratory services. The health facility laboratory was used as a storage room instead of offering laboratory services.

‘When you are sick all you are given is paracetamol and told to go to doctor X’s house or clinic to buy a certain medicine and the laboratory is not functional’, WM 3.

3.4. Unavailability of the health services on weekends, public holidays and during late hours

All participants alluded to the fact that health services at the facility were available only on Monday to Friday of the week with closure of the facility on weekends/public holidays and afterhours on weekdays. Yet the policy requires every facility with maternity wing to operate seven days a week and 24 hours a day.

‘The health workers stay far away from the health center and it takes time for them to reach the health center. When you arrive you first have to look for her to get the health service’, WM 6.

3.5. Intervention of the problem by LePSA method

The meetings were held in the village council office as well as in Kileo village with the aim of giving feedback and to enhance community own self-discovery and action plan. It employed a scenario of a woman in labour pain seeking service in a small health facility with similar problems to those happening in their own community with a number of questions and how to resolve such problems. They were asked if they are empowered to do something and asked to make an action plan.

From the scenarios the participants identified the problem of lack of amenities as being similar to the problem experienced in their village.

To address the problem it was agreed that the two villages work together to improve their HC infrastructure; the village council and Ward Development Committee (WADC) to include the HWs in their meetings; the HWs to improve quality of services provision and KCMUCo to frequently visit the HF and assist in the improvement of laboratory services. The participants from both villages requested the research team to provide them with set standards of a dispensary and a health center. The action plan was then given to the VEO for implementation and presentation to the forthcoming WADC. The findings were to be shared with the Council health committee.

3.6. Results of the study intervention

At the beginning of 2015 and 2017 the team together with the senior community health lecturer visited the HC to assess the plan implementation that revealed some improvement in the health laboratory. Despite the fact that the laboratory was not yet functional due to lack of reagents, it was nonetheless becoming impressive and fitting. In addition, the HF now has a trained laboratory technician. Improvement in other quality parameters is yet to be done.

4. Discussion

4.1. Understanding the situation in the village leading to poor health services

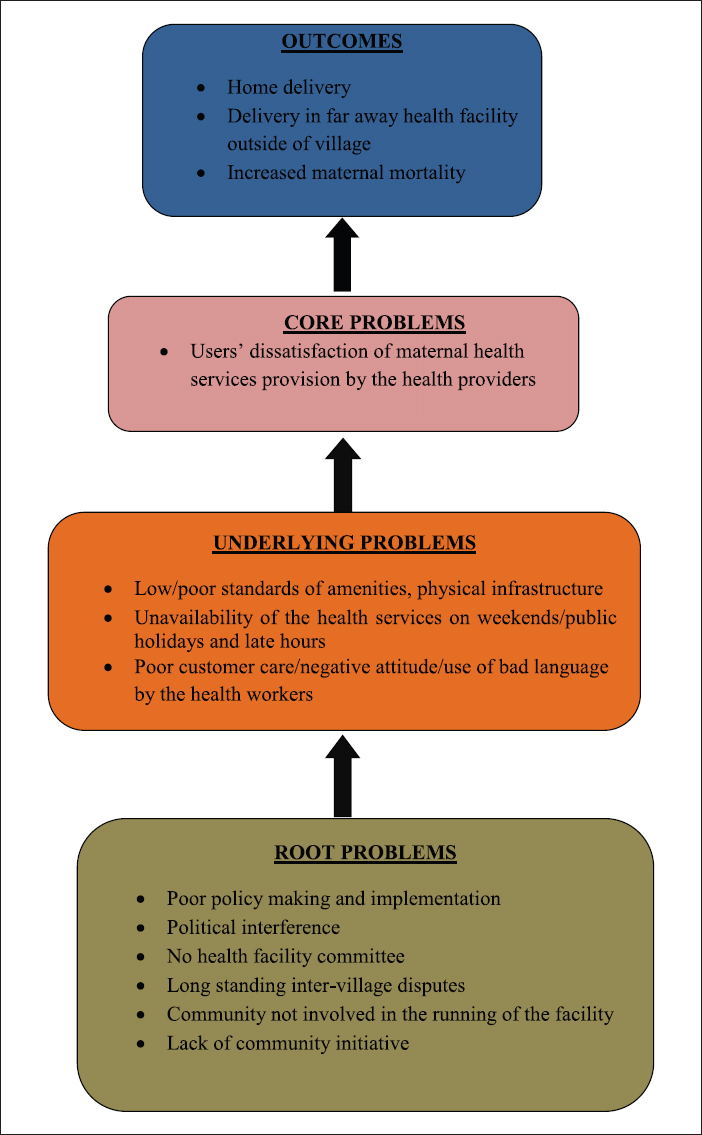

The situation in the village can be a complex one to understand as there are many problems compounding one another and resulting in a long chain of problems as illustrated in the problem tree flowchart (Figure 1). The root problems are political interference and inter village disputes. In the previous years, the village was one with the HC serving them. As population grew the village was divided into Kileo and Kivulini. The HC retained the name of Kileo but meant to serve both villages. However, the Kivulini community do not have a sense of ownership of the HC complaining with the feeling that the spate of poor health service delivery and poor attitude of the HWs are deliberately done against them.

- Problem Tree of the Situation in the Village Affecting Maternal Health Services Delivery

4.2. Poor attitude of the health worker

Poor HW attitude impacts negatively on the quality of care. Findings of this study indicate that majority of the community remains dissatisfied with the level of quality service delivery attributed to their poor attitude.[17] A study by Njau and Khamis in 2014 that reported similar results signifying the indispensable role of respect and compassion by caregivers in customer satisfaction.[18]

4.3. No improvement in staff and physical infrastructure

The research team noted failure of the HF under study to meet the set standards of a health center as per the National Health Policy. Neither did it fulfill the criteria of the Standard Based Management and Recognition much as it lacked the basic needs of the set standards such as under-staffing. The laboratory room currently served as a storage room. Studies conducted in Tanzania have shown neglect of PHC facilities in favor of hospitals. Such studies have revealed erratic availability of power, water supply and transport at PHC facilities.[19] The poor equipment of Kileo HF with resultant poor service delivery could convincingly explain as to why so few customers opted to deliver at the HF.

4.4. Unavailability of the health services on weekends/public holidays and late hours

According to the Tanzanian Government health policy, health facilities running inpatient services are required to operate on a 24-hour basis daily.[20] Majority of dispensaries in Tanzania routinely operate between 8am and 4pm only and are closed on weekends and public holidays. Ideally in such circumstances, a staff member should remain on call to provide service in case of an emergency.[21] However, it was found out that on weekends and late hours there is no staff at the HF leading to unnecessary delay in offering service. There have been complaints from other parts of Tanzania of health service users experiencing a similar problem of closure of dispensaries on weekends or late at night and unwillingness of staffs to provide services at these times.[22]

4.5. Overlapping of politics in quality health services delivery

The politics that took place years before have had a major impact in the mismatch of service provision due to verbal upgrading from dispensary to HC level. The Kivulini residents feel that the HF is for Kileo residents. The continued dispute between the two villages of Kileo and Kivulini in regard to the HF has negatively affected the situation as they fail to work together to improve the HF. National policy works towards every village to have a dispensary and every ward to have a HC.[23] It should however be implemented in an orderly manner taking into account distance from one village to another, population served and resource allocation. It being rushed results in incoordination between policy makers and implementers (professionals) leading to mismatch in services, as the professionals are not adequately supported with necessary resources.

4.6. Recommendations

We advise the District Health Management Team (DHMT) to sustainably follow and maintain the policy on supervision of PHC facilities and on the job staff development for sustained quality health care delivery to the community in the midst of limited resources. We encourage better coordination between health policy makers, DHMT, institutions, health professionals and community so as to improve quality of health services in PHC. The two village leaderships need to work harmoniously together and with the DHMT and Kileo HF for improved health care delivery to the two communities.

5. Conclusion and Global Health Implications

This study reveals that the quality of maternal health services provided at the HF is not up to standard. Clients are dissatisfied with the quality of services provided especially in the dimensions of staff attitude, medical equipment, drug availability and limited health service accessibility. With the help of the AR through LePSA intervention there has been some improvements in the medical amenities and services in the health laboratory. By the joint efforts of all stakeholders involved there shall be improvements in the foreseeable future in other dimensions of quality health services provision.

This study shows that it is important to allow self-diagnosis in a community and to propel self-community interventions to improve rural health services and achieve prosperous and healthy communities. The policy makers need to work with the community and adopt the bottom-up approach methodology in attending to the community health needs. The government, researchers and other stakeholders have key roles in the elimination of health disparities and unhealthy political mingling in health care.

Acknowledgements

Our work is dedicated to the communities of Kivulini and Kileo. Our deeply felt appreciations and thanks to the entire KCMC Department of Community Health for their invaluable lectures and mentoring and indeed their support that enabled us to accomplish this work. We deeply thank Professor Ben Hamel, Dr. Rachel Manongi, Dr. Melkiory Masatu, Dr. Bernard Njau as well as Dr. John Makuka for their invaluable input.

Conflict of Interest: Authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by an Institutional Review Board.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from the study participants.

REFERENCES

- Health System Support for Childbirth Care in Southern Tanzania : Results from a Health Facility Census. BMC Research Notes. 2013;6:435.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of Birth Preparedness, Decision-Making on Location of Birth and Assistance by Skilled Birth Attendants among Women in South-Western Uganda. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35747.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2012. National Bureau of Statistics: Population and Housing Census. Available from: http://www.meac.go.tz/sites/default/files/Statistics/Tanzania%20Population%20Census%202012.pdf

- United Republic of Tanzania: Countdown to 2015: Maternal, Newborn and Child survival 2010. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Reproductive and Health Section; Available from http://www.countdown2015mnch.org/country-profiles/tanzania-united-republic-of

- 2014-2019. Ministry of Health of United Republic of Tanzania: Staffing levels for ministry of health and social welfare departments, health service facilities, health training institutions and agencies. Available from: http://www.jica.go.jp/project/tanzania/006/materials/ku57pq00001x6jyl-att/REVIEW_STAFFING_LEVEL_2014-01.pdf

- Ministry of Health: Standards- Based Management and Recognition for Improving Quality in Maternal and Newborn care 2011. Available from: https://www.k4health.org/sites/default/files/SBMR_Tanz_Health%20Center_FINAL%205%20May.pdf

- Quality of care for pregnant women and newborns- the WHO vision. World Health Organisation 2015 doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13451

- [Google Scholar]

- Client’s Satisfaction on Maternity Services at Paropakar Maternity and Women’s Hospital, Kathmandu. Journal of Health and Allied Sciences. 2010;1:56-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Effectiveness of Birth Plans in Increasing Use of Skilled Care at Delivery and Postnatal Care in Rural Tanzania : a cluster randomised trial. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2013;18:435-43. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12069

- [Google Scholar]

- Why give birth in health facility ?Users’ and providers’ accounts of poor quality of birth care in Tanzania. BMC Health Services Research. 2013;13:174.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of intrapartum care at Mulago national referral hospital, Uganda: clients’ perspective. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:162.

- [Google Scholar]

- Client’s Satisfaction on Maternity Services at Paropakar Maternity and Women’s Hospital, Kathmandu. Journal of Health and Allied Sciences. 2010;1:56-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Effectiveness of Birth Plans in Increasing Use of Skilled Care at Delivery and Postnatal Care in Rural Tanzania : a cluster randomised trial. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2013;18:435-43. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12069

- [Google Scholar]

- Involving Deprived Communities in Improving the Quality of Primary Care Services : does participatory action research work ? BMC Health Services Research. 2007;7:88. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-88

- [Google Scholar]

- Participatory Action Research to Understand and Reduce Health Disparities. Nursing Outlook. 2005;53:121-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- “Being treated like a human being”: Attitudes and behaviors of reproductive and maternal health care providers Mother and baby in the marketplace in Lagos 2012. Available from https://www.burnet.edu.au/system/asset/file/1408/Holmes_et_al_attitudes_review_sept2_final.pdf

- Patients’level of satisfaction on quality of health care at Mwananyamala hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Health Services Research. 2014;14:400.

- [Google Scholar]

- Available from: https://ihi.eprints.org/2448/1/SARA_2012_Report.pdf

- Minimum Standards for Health Facilities Providing Medically Assisted Treatment Of Drug Dependence in Tanzania 2010. Available from: http://www.pmo.go.tz/index.php?option=com_docman& task=doc_download& gid=49& Itemid=91

- Unfulfilled expectations to services offered at primary health care facilities : Experiences of caretakers of underfive children in rural Tanzania. BMC Health Services Research. 2012;12:158.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health services delivery by the Bukoba municipal council: what has quality got to do with it? 2012. ESRF discussion paper No.43. Available from: http://esrf.or.tz/docs/bukoba_mc_healthreport2012.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- 2008-2013. Ministry of Health: Human Resource for Health Strategic Plan. Available from: http://ihi.eprints.org/798/1/MoHSW.pdf_(23).pdf