Translate this page into:

Maternal Mortality at the Dori Regional Hospital in Northern Burkina Faso, 2014-2016

∗Corresponding author email: zamanehyacinthe@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background:

Maternal mortality is of considerable magnitude. It is particularly relevant to developing countries, including those in Sub-Saharan Africa. The aim of this work was to study the cases of maternal deaths in the Dori Regional Hospital, Burkina Faso in the Sahel region, by analyzing the epidemiological aspects of these deaths in order to guide decision-making.

Methods:

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study which spanned the period from January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2016. Cases of maternal death and live births that occurred in the hospital during this period were collected by documentary review.

Results:

A total of 141 maternal deaths and 2,626 live births were recorded with a maternal mortality ratio of 5,369 for 100,000 live births. In 99 (72.20%) cases, death occurred in the postpartum. A home delivery had been reported in 33.70% of cases. Direct obstetric causes were found in 72.10% of cases. They were mainly represented by infections (32.40%) and hemorrhages (23%). Anemia was the indirect cause of death in 25 women (17.80%). The delay in health care access and the lack of blood products contributed to maternal deaths in 64.50% and 26.20% of cases.

Conclusion and Global Health Implications:

An intensification of awareness-raising messages about the importance of the rapid use of health care is necessary. Also, systematic audits of maternal deaths in the care environment and in the community would make it possible to clarify the determinants of maternal mortality in the Sahel region and to provide adequate solutions.

Keywords

Maternal Death

Maternal Mortality

Women’s Health

Burkin Faso

Dori Hospital

Sahel Region

1. Introduction

1.1 Background of the study

Maternal mortality is a major public health problem in particular in developing countries.1 The international community had made commitments through the Millennium Development Goals for its reduction.2 Nevertheless, in Sub-Saharan Africa, the maternal mortality ratio was 546 for 100,000 live births (LB) in 2015.3 This ratio was 614 for 100,000 LB in Cote d’Ivoire4 in 2012 and 368 in Mali5 in 2013. In Burkina Faso, the fight against maternal death is one of the priorities of the Ministry of Health.6 Despite multiple efforts that are made, the maternal mortality ratio remains still high (330 for 100,000 live births).7 In 2014 this ratio was 303.3 for the Sahel region.8 In this Sahel region, the desired fertility rate is at a higher level than the national value (7.2 vs 5.5) while the proportion of assisted births is lower (35.90% vs. 67.10%).9 These indicators reflect a greater exposure of women in this region to the risk of maternal death. The Regional Hospital Center of Dori is the reference center for the four health districts in the region. In this hospital most maternal deaths in the Sahel region occur. This situation motivates our study to provide clarification on the sociodemographic characteristics of deceased women and above all to determine the causes of these maternal deaths. In addition, the study would guide decision-making and advocacy in the fight against maternal deaths.

1.2 Objectives of the study

The aim of this study was to examine the cases of maternal deaths in this Regional Hospital Center in order to provide data to guide decision-making. The specific objectives were to determine the maternal mortality ratio at Dori hospital, describe the socio-demographic characteristics of deceased women, determine the causes of maternal deaths and determine the factors contributing to the occurrence of death.

2. Methods

This was a cross-sectional study that covered the period from January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2016. Cases of maternal death and live births during the relevant period were collected. Sociodemographic characteristics, gynecological and obstetrical histories, variables related to the history of pregnancy, obstetric complications, causes of death, contributing factors to the occurrence of death were collected from birth records, clinical records, operating room registers, maternal death audits and system data of health information. EPI info software 7.1.5.2 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta, GA, USA) and Excel 2007 were used for calculating ratios, frequencies, proportions and averages. The study was completed as part of the West Africa Field Epidemiology Training Program. An authorization to investigate was obtained from the hospital authorities. The anonymity and confidentiality of the data have been respected. Findings from this study will be useful in guiding decision-making and advocacy in the fight against maternal deaths in Burkina Faso, and perhaps other African and developing countries.

3. Results

3.1 Sociodemographic characterisitcs

The average age of deceased women was 24.2 (± 6.50) years ranging from 14 to 43 years. They came from peripheral maternity units in the Sahel region in 132/141 (93.60%) cases. The average distance travelled was 55.80 kilometers ranging from less than one to 100 kilometers. Table I discusses women in the study according to sociodemographic characteristics, namely social status, marital status, number of pregnancies and parity.

| Characteristics | Number(N) | Percentage(%) |

|---|---|---|

| Socio-professional status | ||

| Housewife | 138 | 97.80 |

| Student | 01 | 0.80 |

| Not specified | 02 | 1.40 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 132 | 93.60 |

| Widow | 1 | 0.80 |

| Not specified | 8 | 5.60 |

| Number of pregnancy | ||

| 1 | 46 | 32.60 |

| 4 to 6 | 54 | 38.40 |

| 7 and more | 37 | 26.20 |

| Not specified | 04 | 2.80 |

| Parity | ||

| 0 | 22 | 15.60 |

| 1 | 38 | 26.90 |

| 2 to 3 | 36 | 25.60 |

| 4 to 6 | 31 | 22.00 |

| 7 and more | 10 | 07.10 |

| Not specified | 04 | 2.80 |

3.2 Maternal mortality ratio

During the study period, 141 maternal deaths and 2,626 live births were recorded, representing a maternal mortality ratio (MMR) of 5,369 for 100,000 live births. The distribution of the mortality ratio by year is summarized in Table 2. The mortality ratio was important for teenage girls under the age of 15 and for women who came out of the Dori Health District. The distribution of the maternal mortality ratio by age and provenance of the patients is contained in Table 3.

| Year | Live births | Maternal deaths | MMR for 100 000 live birth |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 760 | 45 | 5,921 |

| 2015 | 815 | 49 | 6,012 |

| 2016 | 1,051 | 47 | 4,472 |

| Total | 2,626 | 141 | 5,369 |

| Age and provenance | Live birth | Number of deaths | MMR for 100,000 LB |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age groups (n=139) | |||

| 10 to 14 | 9 | 1 | 11, 111 |

| 15 to 19 | 665 | 39 | 5, 865 |

| 20 to 24 | 646 | 40 | 6, 192 |

| 25 to 29 | 501 | 24 | 4, 790 |

| 30 to 34 | 468 | 24 | 5, 128 |

| 35 to 39 | 256 | 6 | 2,343 |

| 40 to 45 | 81 | 5 | 6, 173 |

| Provenance (n=141) | |||

| Dori | 2,277 | 82 | 3, 601 |

| GoromGorom | 94 | 28 | 29, 787 |

| Sebba | 80 | 20 | 25, 000 |

| Djibo | 2 | 2 | 100, 000 |

| Districts outside health region* | 173 | 9 | 5, 202 |

3.3 Clinical characteristics

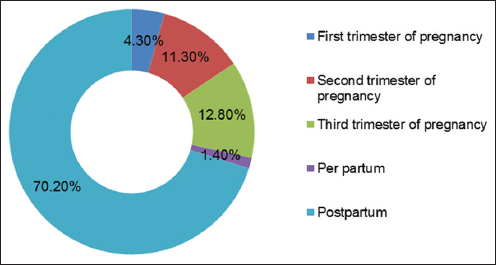

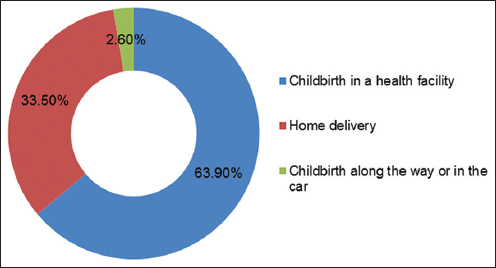

The average number of prenatal visits carried out was 1.5 ranging from zero to four. In 99 (72, 20%) cases, death occurred in the postpartum period (Figure 1), including 84 deaths after a low birth and 15 after a caesarean section. Childbirth occurred at home in 27 cases (33.70%). The distribution of maternal deaths as a function of the vaginal delivery site is shown in Figure 2. The length of stay at the hospital in Dori before death was less than 24 hours in 89/139 (64. 00%) women.

- Distribution of maternal deaths as a function of obstetrical period in Dori Hospital, Burkina Faso, 2014-2016 (n = 141)

- Distribution of maternal deaths in Dori hospital based on the vaginal delivery site, 2014-2016 (n = 80)

3.4 Causes of maternal death

Direct obstetric causes were predominant with 101/139 cases (72.10%). Infection was the leading cause of death with 45 cases (32.10%). Anemia was the indirect cause of death in 25 women (17.80%). Table 4 summarizes the causes of maternal death reported.

| Causes | Number (N) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Direct obstetric causes | 101 | 71.60 |

| Infection | 45 | 31.90 |

| Hemorrhage | 32 | 22.70 |

| Eclampsia | 19 | 13.50 |

| Abortion | 5 | 3.50 |

| Indirect obstetric causes | 38 | 27.00 |

| Anemia | 25 | 17.80 |

| Malaria | 4 | 2.90 |

| Asthma | 1 | 0.70 |

| Cervico cellulite-facial | 1 | 0.70 |

| Anaphylactic shock | 1 | 0.70 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 1 | 0.70 |

| Heart failure | 1 | 0.70 |

| Acute pulmonary edema | 1 | 0.70 |

| Quinck Edema | 1 | 0.70 |

| Malaria+dengue hemorrhagic fever | 1 | 0.70 |

| Thrombophlebitis+hypoglycemia | 1 | 0.70 |

| Not specified | 2 | 1.40 |

3.5 Contributing factors to maternal death

The late arrival in first-level health facility was the main contributing factor to maternal death (64.50%). Contributing factors are summarized in Table 5.

| Contributing factors | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Late arrival in the establishment | 91 | 64.50 |

| Lack of blood | 37 | 26.20 |

| Late transfer to the most appropriate level of care | 31 | 21.90 |

| Treatment mismatch | 8 | 5.70 |

| Other* | 3 | 2.10 |

4. Discussion

The maternal mortality ratio was high (5,369 for 100,000 LB). This ratio is 16 times higher than the value found across the country in 2015 (330 for 100,000 LB).7 It was also two to three times higher than that found by Kaur et al10 in India, Umar et al11 in Angola and Olamijulo et al12 in Nigeria (respectively 2,054; 1,830 and 2,096 for 100,000 lb). These studies took place in university hospitals with specialist doctors, unlike the hospital of Dori, which did not have a gynecologist from 2014 to 2015. However, the trend was beginning to decrease in 2016. With the arrival of a gynecologist, MMR fell from 6,012 in 2015 to 4,472 for 100,000 LB in 2016. Also, the region is mostly populated by communities in which the tradition of home delivery is still strongly present. This reflects the proportion of cases of unattended childbirth that was 33.70% in our study. This exposes the parturients to the risk of complications such as uterine rupture and hemorrhage. In fact, hemorrhage was the second cause of death (23%) after infection (32%) in our study.

Maternal death was higher among young women. The age range of 15 to 34 years was preponderant (91.4 %) with a mean age of 24.2 years ranging from 14 to 43 years. This average age was closer to that reported by Gumanga et al13 in Ghana (25 years) in a study that focused on 280 cases of maternal deaths. In contrast, it was lower than the rates (28.2) reported by Bukar et al in Nigeria (with 54 cases of maternal deaths) and 28.4 reported by Thiam et al in Senegal in a series of 308 cases of maternal deaths (p < 0.005).14,15 Early marriage in the Sahel region (16.1 years)9 could explain the low age of our study population. This causes early pregnancies (before age 18) with a frequency of mechanical dystocia due to physical and physiological immaturity.16

The average number of antenatal care delivered was 1.5 visits ranging from zero to four. Thiam et al in Senegal and Sayinzoga et al in Rwanda found an average number from one to two ANC visits in these countries.15,17 A large number of maternal deaths could be avoided by proper follow-up of the pregnancy. Deaths were mainly observed during postpartum periods (70.2%). Sayinzoga et al and Balde et al found lower proportions (44.9% and 16%, respectively).17,18 Our findings are comparable to those of Magoma et al in Tanzania (73.3%), Traore et al in Mali (72.4%) and Khumanthem et al in India (70%).19-21 Lack of care during childbirth and postpartum may explain some cases of per-postpartum death. Similarly, home deliveries, delay in consultation and lack of blood products were the main contributors to death during this period. In fact, 64 of the women who died in the postpartum period consulted late and 25 did not benefit from an emergency transfusion.

Direct obstetric causes were predominant (71.63%) in our study population. This finding was similar to prior studies.12, 17, 18, 22 The main direct obstetric cause was infection (31.90%) as found by Gumanga et al, followed by hemorrhages (22.70%) and anemia (17.70%).14 These three causes can be prevented and should be given special attention in the follow-up of pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum.

Indirect obstetric causes accounted for 23.40% of maternal causes of death. Anemia occupied the first place of these causes as noted in the literature.10, 23 Anemia is multifactorial and could be prevented by routine iron supplementation during pregnancy and research as well as taking into account other curable causes of anemia.

The late arrival of the patients in the care facility (64.50%), their late transfer to the reference center (21.90%), the lack of blood products (26.20%) for their management in cases of hemorrhage or severe anemia were the major contributing factors in the occurrence of death. Some maternal deaths could have been avoided if the families were to consult at the onset of the first signs of severity. Effort should be made for the availability of blood products and the permanent functioning of the surrounding surgical antennas which would help to reduce the long distances travelled by pregnant women and families in search of appropriate care in case of obstetric complications.

4.1. Limitations

The limitations of our study were that of a retrospective study with missing data in medical records. The missing data was not included in the analysis. In addition, the study had difficulty evaluating the dysfunctions in the original health structures and determining community causes in the occurrence of maternal deaths. The assessment of the community determinants of maternal deaths could be done by verbal autopsy in a population environment in a complementary sociological approach.

4.2. Recommendation for further studies

Systematic audits of maternal deaths in the care environment and in the community would make it possible to better clarify the determinants of maternal mortality in the Sahel region in order to complement our study. This may certainly provide potential and adequate solutions. The continuation of the study in the community environment would help to identify the sociological aspects contributing to maternal deaths.

5. Conclusion And Global Health Implications

The maternal mortality ratio in Dori remains high and this mortality affects young women in particular. The main causes of death identified were infection, hemorrhage, anemia and eclampsia. The factors contributing to maternal deaths were essentially the delays in consultation, the delays in obtaining healthcare, and the lack of blood products. An intensification of awareness-raising messages about the harms of early pregnancies and the importance of the rapid and timely use of health care are necessary. Systematic audits of maternal deaths in the care environment and in the community would make it possible to clarify the determinants of maternal mortality in the Sahel region and to provide adequate community-driven solutions.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their heartfelt thanks to the Director General of the Hospital of Dori for having authorized the realization of the study, staff of the hospital for his contribution during the data collection, and staff for the supervision of the Master WA-FELTP of the Université Ouaga 1 Prof. Joseph KI Zerbo of Ouagadougou for his support in carrying out the study and writing the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Ethics Approval: The study was the subject of a master’s thesis in the West African Field Epidemiology Training Program (WA FETP). An authorization to investigate was obtained from the hospital authorities. The anonymity and confidentiality of the data have been respected.

References

- WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank, United Nations. 2014. Trends in maternal mortality:1990 to 2013. Geneva: World Health Organization; http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/112682/9789241507226_eng.pdf;jsessionid=0D8A59586BECE3BC715669D7031 9C217?sequence=2

- [Google Scholar]

- 2011. Nations Unies. Objectif du millénaire pour le développement. Rapport 2011. New York: Nations Unies; http://www.un.org/fr/millenniumgoals/pdf/report_2011.pdf

- OMS/UNICEF/UNFPA/Groupe de la Banque mondiale et la Division de la population des Nations Unies:Tendance de la mortalitématernelle 1990-2015. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/204113/WHO_RHR_15.23_fre.pdf;jsessionid=620E130ECB3B34075673BFF59 9E96AAA?sequence=1

- Ministère de la Santéet de la Lutte contre le Sida, Institut National de la Statistique, Ministère d'État, Ministère du Plan et du Développement, Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire. Enquête démographique et de santéet àindicateurs multiples (EDS-MICS) 2011-2012. Consultéle 25 octobre 2018. http://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/1635/study-description

- Cellule de Planification et de Statistiques, Institut National de la Statistique, Centre d'Études et d'Information Statistiques Bamako, Mali. Enquête Démographique et de Santé(EDSM V) 2012-2013. http://www.sante.gov.ml/index.php/annuaires/download/8-enquetes-demographiques-de-sante/4-eds-v-2013

- Ministère de la santédu Burkina. Plan national de développement sanitaire 2011-2020, Burkina Faso https://www.uhc2030.org/fileadmin/uploads/ihp/Documents/Country_Pages/Burkina_Faso/Burkina_Faso_National_Health_Strategy_2011-2020_French.pdf

- Ministère de santé, Burkina Faso. Profil sanitaire complet du Burkina Faso. Module 1 Situation socio-sanitaire du Burkina Faso et mise en œuvre des ODD 2017 https://afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2018-08/Profil%20sanitaire%20complet%20du%20Burkina%201.pdf

- 2015. Ministère de l'économie, des finances et du développement, Institut national de la statistique et de la démographie, Burkina Faso. Annuaire statistique. http://www.insd.bf/n/contenu/pub_periodiques/annuaires_stat/Annuaires_stat_nationaux_BF/Annuaire_stat_2015.pdf

- 2010. Institut National de la Statistique et de la Démographie Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Enquête Démographique et de Santéet àIndicateurs Multiples (EDSBF-MICS IV) Burkina Faso. http://www.insd.bf/n/contenu/enquetes_recensements/enq_demo_sante/edsbf_mics_rapport_definitif.pdf

- Trends in maternal mortality ratio in a tertiary referral hospital and the effects of various maternity schemes on it. J Family Reprod Health. 2015;9:89-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Maternal mortality in the main referral hospital in Angola, 2010-2014:understanding the context for maternal deaths. Int J MCH AIDS. 2016;5:61-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Trends in maternal mortality at the Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Lagos, Nigeria. Nig Q J Hosp Med. 2012;22:72-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Trends in maternal mortality in Tamale Teaching Hospital, Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2011;45(3):105-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Maternal mortality at federal medical centre Yola, Adamawa state:a five-year review. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3(4):568-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Maternal mortality at the Centre De Sante Roi Baudouin (Dakar –Senegal):About 308 Cases. Mali Médical. 2014;Tome xxix(N°3)

- [Google Scholar]

- Organisation mondiale de la santé. In: La grossesse chez les adolescents, Aide-mémoire N°364, septembre 2014. Geneve: OMS; 2014.

- [Google Scholar]

- Maternal death audit in Rwanda 2009–2013:a nationwide facility-based retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1)

- [Google Scholar]

- Review of maternal deaths in the service of obstetrics gynecology hospital national Donka CHU Conakry (Guinea) Rev Int Sc Méd – RISM. 2016;18(2):99-103.

- [Google Scholar]

- Maternal death reviews at Bugando hospital north-western Tanzania:a 2008-2012 retrospective analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:333.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mortalitématernelle au service de gynécologie-obstétrique du Centre hospitalier régional de Ségou au mali:étude rétrospective sur 138 cas. Mali Médical. 2010;Tome XXV(n°2)

- [Google Scholar]

- Maternal mortality and its causes in a tertiary center. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2012;62(2):168-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Maternal mortality in Ghana:a hospital-based review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91(1):87-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Maternal mortality at the State Specialist Hospital Bauchi, Northern Nigeria. East Afr Med J. 2009;86:25-30.

- [Google Scholar]