Translate this page into:

Oral Health Status of People with Sickle Cell Disease at a Major Hospital in Cameroon

*Corresponding author: Ashu Michael Agbor, Department of Oral Health/Dentistry, Universite des Montagnes, Bangnagte, Cameroon. agborasm@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Agbor AM, Mekendja KF, Che B, Naidoo S. Oral health status of people with sickle cell disease at a major hospital in Cameroon. Int J MCH AIDS. 2025;14:e010. doi: 10.25259/IJMA_28_2024

Abstract

Background and Objective:

Sickle cell disease is a neglected inherited condition that affects the hemoglobin in red blood cells and impacts at least 2% of the West African population. This hemoglobinopathy presents with high mobility and mortality as a result of infections and vaso-occlusive pain crises as a result of structural abnormality of the red blood, making it fragile and rigid. The objective of our study was to describe the oral health status of sickle cell patients in Yaoundé Central Hospital, Cameroon.

Methods:

A descriptive cross-sectional study was carried out in the hematology unit of the Yaoundé Central Hospital from June to October 2022.

Results:

A total of 63 patients, made up of 41 (65%) males and 22 (35%) females, were recruited in the study. The majority, 60 (95%), consumed sugary foods, while 43 (68%) brushed their teeth before meals, and 27 (43%) brushed their teeth once a day. A third, 24 (38%), presented with pallor of the palatal mucosa, and 24 (74.6%) had dental caries. The mean decayed, missing, and filled teeth index of this population was 2.6 (moderate) and 11 (17.5%) periodontitis. Less than a third, 17 (26.9%) of the patients had been to a dentist, 26 (41.3%) did not see it necessary to consult a dentist, while 23 (37%) thought that oral conditions are not serious. Two-thirds, 38 (60.5%), did not receive any treatment for caries. Tooth extraction 18 (27.9%) was the most common treatment given, 5 (7%) conservative treatment, and no treatment was administered for periodontitis.

Conclusion and Global Health Implications:

There was a high prevalence of periodontal diseases, moderate levels of dental caries, and elevated prevalence of oral mucosal lesions like tonsillar hypertrophy, pallor of the palate, lingual mycosis inflammation, and mucositis among sickle cell patients. The poor oral health-seeking behavior of the patients and poor oral hygiene practices might be responsible for the high burden of carious and periodontal diseases.

Keywords

Cameroon

Dental Caries

Oral Health

Periodontal Diseases

Sickle Cell Disease

INTRODUCTION

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a genetic disease that affects the hemoglobin of red blood cells.[1] This hemoglobinopathy is due to a structural abnormality of the beta chains of hemoglobin, leading to the production of hemoglobin S, where the hydrophilic glutamic acid is replaced by a hydrophobic valine.[2]

Sickle cell anemia is the most common form of SCD, with a lifelong affliction of hemolytic anemia requiring blood transfusions, pain crises, and organ damage.[3,4] Cameroon has more than two million sickle cell patients (1–2% of the population), and 25–30% of the Cameroonian population carries the gene. It is likely to pass it on to their descendants, therefore posing a public health problem.[5]

The diagnosis of SCD is based on the formal identification of abnormal hemoglobin. Screening is generally carried out by isoelectric focusing or by electrophoresis on cellulose acetate at alkaline pH. Some laboratories prefer to use high-performance liquid chromatography on a cation exchange column as a first step.[6]

The management of SCD should involve a multidisciplinary approach that concerns all specialties of medicine. Mbiya (2021) suggested that, in addition to complications due to vaso-occlusive accidents, anemia, infections, and epistaxis, it is necessary to systematically look for the presence of hypertrophy of the tonsils, glossitis, maxillary malocclusion, and dental caries, which are significant oral manifestations of the disease.[7] He emphasized that these anomalies are common and should justify a consultation with the dentist and ENT specialist.[7]

Given their high morbidity and socio-economic impact, oral diseases constitute a major public health problem, yet they can be avoided. Their consequences, such as pain and functional impairments, have a negative impact on the quality of life of both adults and children as well as their communities.[8,9] In resource-poor settings like Cameroon, the economic burden in the management of oral pathologies (disease of hard and soft tissues of the oral cavity) in children is high because the majority of children are not covered by health insurance.[9] Hence, oral pathologies in children, such as caries, periodontitis, oral cancer, oral infectious diseases, injury-related trauma, and congenital lesions, are common in Cameroon.[10] However, little has been reported on the oral health status of patients with SCD in Cameroon. Therefore, the objective of the current study was to describe the oral health status of children with sickle cell disease in Yaoundé.

METHODS

This is a cross-sectional descriptive study carried out at the hematology and medical oncology department of the Yaoundé Central Hospital between June and October 2022.

Sampling and Eligibility Criteria

Sickle cell patients consulting at the Yaoundé Central Hospital (Laquintinie Hospital in Douala is one of the two national centers for the management of patients with SCD, with consultation and hospitalization services) during our period of study, who gave their assent, and parents who gave their informed consent were selected for the study. Children whose medical conditions did not allow intra-oral examination, whose medical records were incomplete, and whose questionnaires were not completely filled out were excluded. Patients with systemic diseases (hypertension or epilepsy etc.) were excluded from the study.

The convenience sampling technique was used in recruiting participants as all patients who came for consultation in the clinic during the study period and were willing to participate in the study were recruited.

Data Collection Instrument and Technique

An anonymous questionnaire was used to collect personal data of patients, and a data extraction sheet was used to collect data on the clinical observation of the patients. The interest and various objectives of the study were presented to the parents or guardians, as well as to the children of age, to understand and obtain their written, free, and informed consent.

The data collection was carried out in 2 steps; (i) An anonymous questionnaire was issued to collect personal information such as age, residence, oral hygiene and dietary habits, and electrophoretic status. (ii) A data extraction sheet was used in collecting data from the patients’ medical records and also from clinical examination of the patients that was carried out to establish the oral pathologies present in these patients.

Consultation was carried out in the hematology department under bright light on a portable dental unit. The oral examination was subdivided into extra-oral and intra-oral examination.

The dental caries burden in our study population was evaluated using the decayed, missing, and filled teeth (DMFT) index. The DMFT index was graded as follows; Very low level: 0< DMFT <1.1, Low level: 1.2< DMF<2.6, Average level: 2.7< DMF <4.4, High level: 4.5< DMF <6.5, Very high level: DMF >6.5.

The Silness–Löe plaque index (Silness and Loe, 1964) was used to measure oral hygiene status. Dental plaque was recorded for all surfaces of teeth #12, #16, #24, #32, #36, and #44 using a scale ranging from 0 to 3: 0 = no plaque; 1 = film of plaque adhering to the free gingival margin and adjacent area of the tooth, observed in situ only after application of disclosing solution or by using a probe on the tooth surface; 2 = moderate accumulation of soft deposits within the gingival pocket or tooth and gingival margin, visible with the naked eye; and 3 = abundance of soft matter within the gingival pocket and/or on the tooth and gingival margin. The plaque index was calculated by averaging scores from four surfaces of each tooth.[11]

Data Analysis

The data collected were entered using CSPro software version 7.5 and analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software version 25. Bivariate analysis was carried out to establish the statistical relationships between variables. Differences were considered statistically significant for p < 0.05.

RESULTS

We recruited 63 sickle cell patients, made up of 41 (65.1%) males and 22 (34.9%) females. More than a third, 27 (44.4%) of the 18–25 age range, 11 (17.4%) of the 12–18 age range, 10 (15.9%) of the 12–18 years age range 14 (22.2%) and 25 years and above [Table 1].

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 41 | 65.1 |

| Female | 22 | 34.9 |

| Age range (years) | ||

| 1–12 | 11 | 17.4 |

| 12–18 | 10 | 15.9 |

| 18–25 | 27 | 44.4 |

| Above 25 | 14 | 22.2 |

| Genotype | ||

| HbSS (Homozygous) | 60 | 95.2 |

| HbAS (Heterozygous) | 3 | 4.8 |

HbSS: Homozygous sickle cell disease, HbAS: Heterozygous sickle cell disease.

The homozygous strains were predominant 60 (95.2%) and the heterozygous 3 (4.8%) [Table 1].

Distribution of the Study Population According to Oral Hygiene Habits

All patients used a toothbrush and toothpaste as an aid to their hygiene, 45 (68.3%) brushed before meals, while 20 (31.7%) brushed after meals. 32 (55.6%) brush once a day, 30 (49.6%) twice a day, and 1 (1.65%) 3 times a day. All patients consumed sugar and fruits.

Oral Examination

Extra-oral examination revealed that 38 (60.5%) of the patients presented with submandibular and pre-auricular lymphadenopathy.

Oral Hygiene and Gingival Inflammation

The majority 52 (82.5%) of the participants had poor oral hygiene. Good oral hygiene (score of 0) was found in 11 (17.5%) of the participants, 16 (25.4%) presented with visible plaque (score 1), 31 (39.2%) with score 2, and 5 (7.9%) with score 3 [Table 2].

| Score | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 11 | 17.5 |

| 1 | 16 | 25.4 |

| 2 | 31 | 49.2 |

| 3 | 5 | 7.9 |

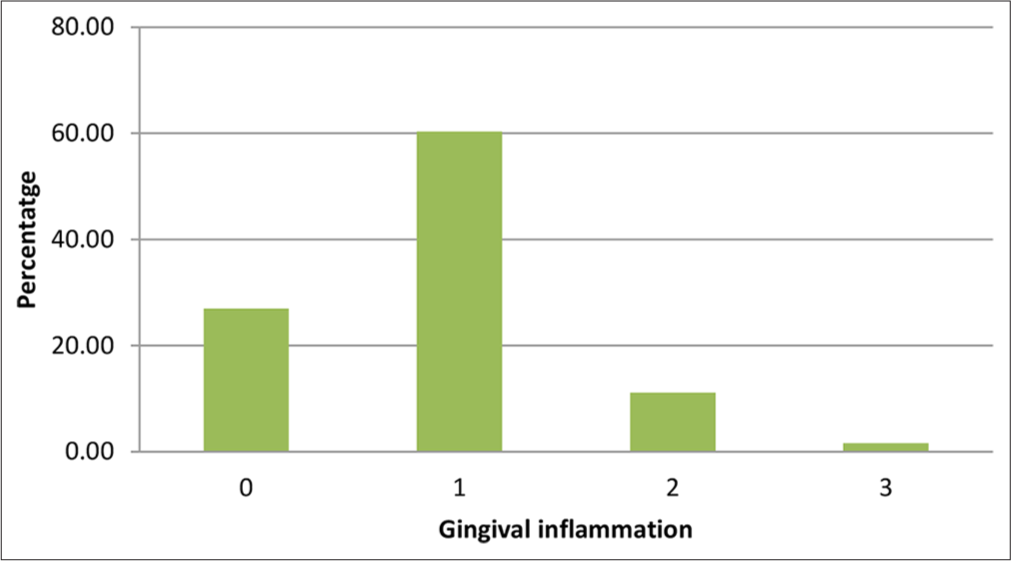

Less than a third, 17 (27%) did not have gingivitis (score 0), 38 (60.3%) presented with mild gingivitis, 10 (11.1%), and 1 (1.63%) severe gingivitis (Score 3) [Figure 1].

- Distribution according to the Silness and Loe gingival inflammation index.

The majority (17.5%) of patients who had periodontitis did not receive any treatment.

Carious Pathology

Mean DMFT index

Dental caries is found in 74.6% of the study population. The average DMFT index was 2.62 (Moderate). The DMFT index of the 1–12 year age group was 2.0 (low), 12–18 years 1.7 (low), 18–25 years 2.7 (average), and above 25 years 3.57 (moderate) [Table 3].

| Age group (years) | DMFT index |

|---|---|

| 1–12 | 2.00 |

| 12–18 | 1.70 |

| 18–25 | 2.71 |

| Above 25 | 3.57 |

| Mean DMFT | 2.62 |

DMFT: Decayed, missing, and filled teeth

Intra-Oral Mucosal Lesions

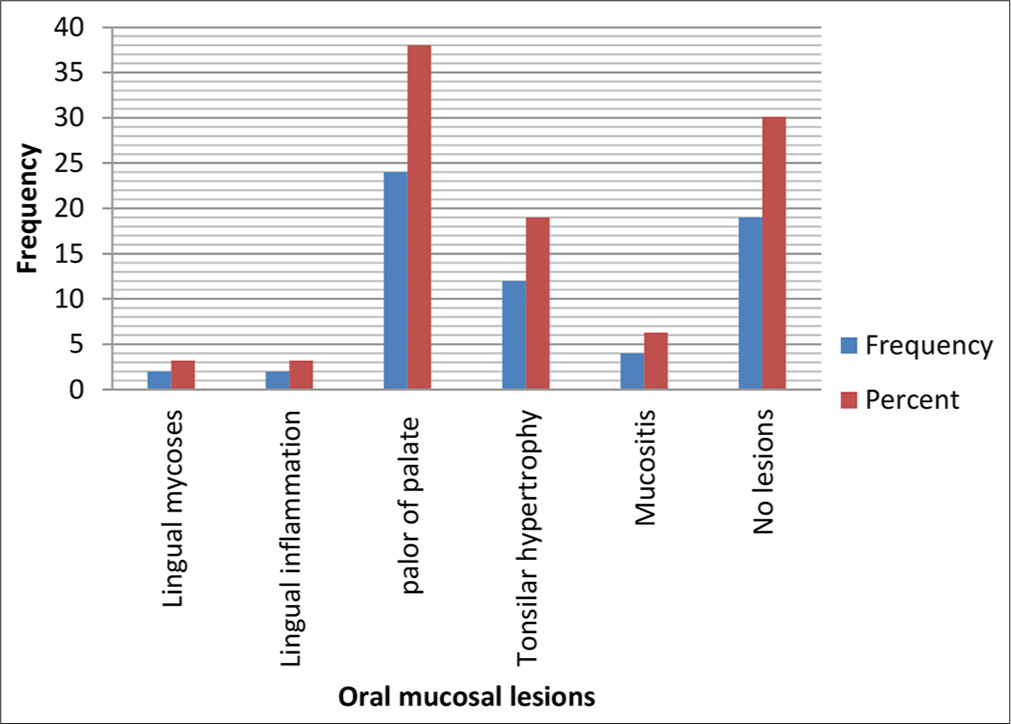

A third, 24 (38%) of the participants presented with pallor of the palate, 12 (19.0%) with tonsillar hypertrophy, 4 (6.3%) mucositis, 2 (3.2%) lingual mycosis (one pseudomembranous and the other villous), and 2 (3.2%) lingual inflammation [Figure 2].

- Soft tissue pathologies.

Hard Tissue Anomalies

Hard tissue anomalies with respect to the positioning of the teeth included version 4 (6.3%), ectopic eruption 3 (4.8%), and rotation 3 (4.8%), while amelogenesis imperfecta 2 (3.6%) was the only structural anomaly observed clinically.

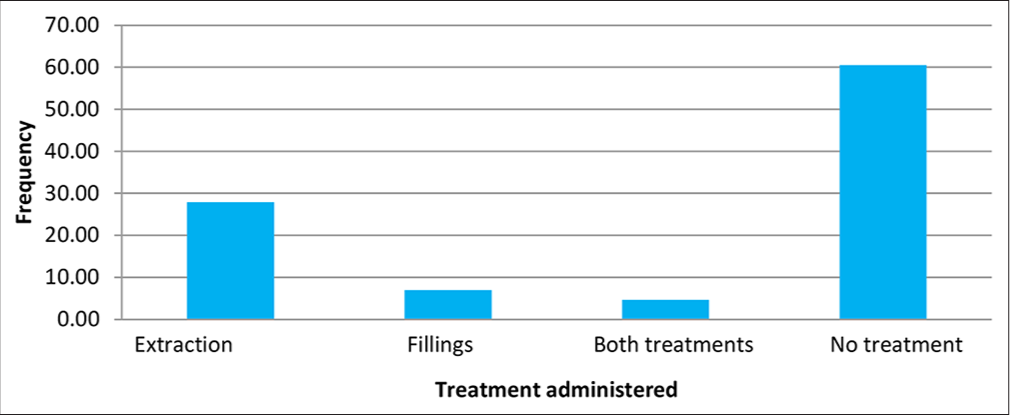

Oral Health-Seeking Behaviors and Management of Caries

Less than a third, 17 (26.9%) of the participants have never been to the dentist 73.1%. Among the patients who visited the dental clinic, 9 (60.5%) did not receive any treatment for tooth decay, 5 (27.9%) had a tooth extraction, 2 (7%) had conservative treatment, and 1 (4.7%) had both extraction and conservative treatment [Figure 3].

- Management of dental caries.

DISCUSSION

SCD poses a serious public health problem among children and adults as it is associated with 3% of births in Africa and an elevated rate of childhood mortality as a result of a life-long affliction with numerous acute and chronic complications responsible for high morbidity and mortality of affected patients.[12,13] Acute complications include hemolytic anemia requiring blood transfusions, pain crises, and organ damage.[3,13] Chronic complications include stunting and delayed puberty, particularly in homozygous patients, mainly because of increased basal metabolism related to hemolysis and chronic inflammation, endocrine disorders related to free iron toxicity on endocrine organs, multiple morbid episodes, micronutrient deficiency, and probably low socioeconomic level.[3,4,14]

Although it affects 20–25% of the population of Cameroon,[13] little interest has been developed in studying the oral health status and the treatment needs of patients affected with sickle cell disease in Cameroon. The current study indicated a high prevalence of periodontal diseases, moderate levels of dental caries, and a high prevalence of oral mucosal lesions like tonsillar hypertrophy among sickle cell patients.

The current study showed that a third, 41 (65.1%) of the participants were males. This male predominance was reported by Ngo et al. (2019) in a study carried out in Yaoundé.[14] It has been argued that the incidence of SCD is not strictly gender-related as it is transmitted as an autosomal recessive disorder. In particular, the gender-related differences in pediatric SCD are not well-characterized.[15] The high frequency of attendance of males in hospitals often gives a biased perception that disease is more predominant in males. A study in Saudi Arabia reported that because males were admitted more often to the stabilization unit for pain control, they were also over-represented they are among those whose pain persisted for over 47 hours and needed hospitalization.[16]

In the current study, two-thirds of the participants were of the 18–25 age group, which is similar to that of a study carried out in Saudi Arabia, where the 13–35 age range was more predominant. This should be because of the increased oral health awareness among these patients.[17]

Oral Hygiene Practices and Diet

In our study, though all the participants had toothbrushes and toothpaste for their oral health care, more than half of the participants had very poor oral hygiene practices. This contradicts a case-control study carried out in Saudi Arabia, where the differences between the cases and controls in the known caries risk factors, such as income level, flossing, and brushing habits, were studied. It was reported that a high level of oral health awareness in sickle cell patients who brushed their teeth in normal daily life was 84.80% compared to 90.91% of the control group.[17] Oral healthcare professionals have to educate these patients and parents on how and why they should maintain good oral hygiene.

In our study, all the participants consumed sugar. Al-Alawi et al. (2015) and Kowe et al. (2022) from Congo reported in their studies that the majority of their patients with SCD were aware of the effects of the disease on their oral health.[17,18] Exposure to cariogenic diets, sweetened medications, and sweets used as pacifiers for these children could be responsible for high caries among these children.

Oral Pathologies

In our study, we noted that two-thirds of the patients presented with chronic lymphadenopathy. The presence of lymphadenopathy indicates the existence of repeated infections.[19,20]

In the current study, the prevalence of dental caries was high (74.6%). Al-Alawi et al. reported a high prevalence of dental caries among patients with SCD. This high prevalence was not significantly different from the control group.[17] They also noted that one of the reasons for the high prevalence of dental caries in their study was that tooth decay was more prevalent, and the number of filled teeth was lower among patients with SCD than among healthy control subjects.[17] This reflects the fact that children with SCD, just like children with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in Cameroon, still have poor access to oral care services.[21]

We found out that the mean DMFT in the current study was moderate (2.62). Other studies reported DMFT indices within the same range.[17-19] We also noted that the DMFT index of our study population increased with age. This is similar to the results obtained by Kowe et al. in Congo, who obtained a DMFT/dmft index of 2.39 ± 3.12/2.29 ± 2.96.[18] The similarities could be explained by the fact that these two countries have similar health structures and feeding habits. These values are higher than the 1.3–1.5 DMFT reported by Fernandes et al. in 2015 in a study carried out in Brazil.[22] We believe that one reason for the discrepancy between their findings and our results may be due to differences in the oral healthcare systems between Cameroon and Brazil. In the Brazilian context, oral health care for pediatric SCD patients is provided free of charge by the government, which is not the case in Cameroon. A study conducted in India found that oral health was not a primary concern of patients with SCD.[3] In the current study, poor oral hygiene and poor oral health-seeking behavior of the patient are the major causes of dental caries and periodontal diseases, prohibiting the patients from taking timely and appropriate action due to frequent hospitalization and vasoocclusive crises, which deterred them from seeking regular dental consultations. Furthermore, the cost of oral health care is high in Cameroon, where there is no government-assisted package for dental services. More than two-thirds of dental patients pay directly out-of-pocket, as only those in the formal sector have insurance in the country.[9]

Our study equally demonstrated that gingivitis was the most common inflammatory condition, as three-quarters of the patients had gingivitis. Other studies have shown that the presence of SCD did not change the oral manifestation of periodontal diseases.[22,23] Individuals with SCD have a higher level of predisposition to developing periodontal disease due to the presence of these pathogens in the mouth, as well as alterations in their cellular and humoral immune response.[24,25] The high prevalence of periodontal diseases in the current study was a result of poor oral hygiene.

More than a third of the participants of our study presented with the pallor of the palatal mucosa, a clinical sign that has often been associated with anemia or ischemia of the palate. Mbiya et al. (2021) also reported that pallor and yellow coloration of the palate are clinical signs of anemia and jaundice that might need clinical intervention.[7] Mutombo et al. (2017) found that the most common oral manifestations of sickle cell anemia are mucosal pallor, yellow tissue coloration, disorders of enamel and dentin mineralization, changes to the superficial cells of the tongue, multiple caries, and periodontal disease that can lead to an odontogenic abscess.[26] Mbiya et al. (2021) emphasized that it is necessary to systematically look for the presence of tonsillar hypertrophy in these patients.[7] In our study, 19% of the population had tonsillar hypertrophy. The presence of tonsillar hypertrophy can be explained by the inflammatory and infectious phenomena caused by this disease. Tshilolo added that the poor oral hygiene of patients, a vulnerability to developing cavities, was linked to SCD from the age of 3.[7] The variation of SCD lesions in the orofacial region and the relation of these lesions with other systemic disease manifestations justify the multidisciplinary approach toward the management of SCD.

The provision of basic oral care was very deficient for most patients in the current study, such that very few of the patients had scaling as prophylaxis for periodontitis. The high rate of tooth extraction in the current study was due to late consultations.[8] Tooth extraction was used as a remedy for tooth pain.

Strength of the study

It highlights the oral manifestations of SCD among children in Cameroon, emphasizing the importance of a multidisciplinary approach and the need for all sickle cell patients to have access to oral healthcare services to improve their quality of life.

Limitation of the study

A comparative study between children with SCD and those without it will show significant differences in the oral health status of these patients.

CONCLUSION AND GLOBAL HEALTH IMPLICATIONS

The current study revealed a high prevalence of periodontal diseases, moderate levels of dental caries, and a high prevalence of oral mucosal lesions like tonsillar hypertrophy, pallor of the palate, lingual mycosis and inflammation, and mucositis among sickle cell patients. The poor oral health-seeking behavior of the patients and poor oral hygiene practices might be responsible for the high burden of carious and periodontal diseases.

Recommendations:

Earlier preventive measures and regular dental care are essential for children with SCD since their health is at risk of being compromised. Experiencing emergency situations often results in frequent hospitalizations and neglect in dental care. These services should be provided especially for preschool children to receive early intervention before their dental health deteriorates. Oral health education should be emphasized in these patients to avoid the sequelae of dental diseases.

Key Messages

1) Sickle cell disease (SCD) impacts both the hard and soft tissues of the mouth, particularly the tissues that support the teeth. 2) It can lead to inflammatory conditions of the oral soft tissues, such as gingivitis, periodontitis, and mucositis. 3) Patients with SCD should schedule regular dental visits, especially when they begin to experience pain or notice any abnormalities in their mouths.

Acknowledgments:

We wish to acknowledge the staff of Laquintinie Hospital for facilitating this study in their facility.

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no competing interests. Financial Disclosure: Nothing to declare. Funding/Support: There was no funding for this study. Ethics Approval: Ethical clearance was obtained from the institutional review board of the Université des Montagnes (No/2021/003/UdM/PR/CIE), and permission to conduct this study from the Regional delegation of the Ministry of Public Health for the Central Region and the Yaoundé Central Hospital where this study was carried out. Declaration of Patient Consent: The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent. Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Assisted Technology for Manuscript Preparation: The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI. Disclaimer: None.

References

- Regional Committee for Africa, 56: Sickle Cell Disease in the African Region: Current Situation and Prospects: Report of the Director-General. 2006 [cited 2024 May 20]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/sickle-cell-disease#:~:text=In%20the%20Region%2C%20the%20majority

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of sickle cell disease: Clinics in mother and child health. . 2004;1(1):6-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetics and pathophysiology of sickle cell disease In: Girot R, ed. Sickle cell anemia. Paris: John Libbey Eurotext; 2003. p. :1-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sickle cell anemia and other hemoglobinopathies. Fact Sheet No 308. [Cited 2024 May 20]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/sickle-cell-disease

- [Google Scholar]

- Inherited haemoglobin disorders: An increasing global health problem. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:704-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improvement of SCD morbimortality in children: Experience in a remote area of an African country. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:294.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reasons for late dental consultations at the central hospital of yaoundé. Cameroon" EC Dent Sci. 2018;17(4):360-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Methods of payment for oral health care in Yaoundé. J Public Health Afr. 2023;14(7):154.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral health practices and status of 12-year-old pupils in the western region of Cameroon. Eur J Dent Oral Health. 2020;1(1):1-6.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Periodontal disease in pregnancy. II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condition. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121-35.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sickle cell disease in Africa: A neglected cause of early childhood mortality. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(6 Suppl 4):S398-405.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Management of haemoglobin disorders-report of joint WHO-TIF meeting. 2006. [cited 2018 Jun 26]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241594929

- [Google Scholar]

- A cross sectional study of growth of children with sickle cell disease, aged 2 to 5 years in Yaoundé, Cameroon. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;34:85.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gender-related differences in sickle cell disease in a pediatric cohort: A single-center retrospective study. Front Mol Biosci. 2019;6:140.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Differences between males and females in adult sickle cell pain crisis in eastern Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2004;24(3):179-82.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The association between dental and periodontal diseases and sickle cell disease. A pilot case-control study. Saudi Dent J. 2015;27(1):40-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral health status of children with sickle cells in Kinshasa, DR Congo. Rom J Oral Rehabil. 2022;14:23-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oral and dental complications of sickle cell disease in Nigerians. Angiology. 1986;37(9):672-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unexplained lymphadenopathy in sickle cell disease. Eur J Haematol. 1988;40(2):155-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral manifestations of HIV infection and dental health needs of children with HIV attending HIV treatment clinics in Western Cameroon. Int J MCH AIDS. 2024;13:e022.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caries prevalence and impact on oral health-related quality of life in children with sickle cell disease: Cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15:68.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dental and periodontal health status of Beta thalassemia major and sickle cell anemic patients: A comparative study. J Int Oral Health. 2013;5:53-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association between sickle cell disease and the oral health condition of children and adolescents. BMC Oral Health. 2018;18(1):169.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serum cytokine profile among Brazilian children of African descent with periodontal inflammation and sickle cell anemia. Arch Oral Biol. 2013;58:505-10.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Management of odontogenic abscess in patients with sickle cell anemia: 5 case reports. Br J Med Med Res. 2017;20:1-5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]