Translate this page into:

Prevalence of Occupational Exposure to HIV and Factors Associated with Compliance with Post-Exposure Prophylaxis Among Health Workers of the Biyem-Assi, Buea, and Limbe Health Districts of Cameroon Maternal and Child Health and AIDS

* Corresponding author email: mathias_mesum@yahoo.fr

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background:

Although a few studies have assessed occupational exposure and knowledge on post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) for HIV among health care workers (HCWs), limited information is available on the factors that influence the use of HIV PEP among HCWs after occupational exposure in Cameroon. This study aimed to assess the prevalence and determinants of occupational exposure to HIV infection and identify factors (knowledge, attitudes, and practices) that influence compliance to the use of HIV PEP among HCWs in the Biyem-Assi, Buea, and Limbe health districts.

Methods:

A stratified cross-sectional study was carried out among health care workers from the Biyem-Assi, Buea, and Limbe health districts of Cameroon. A structured questionnaire adapted from previous studies was administered on the socio-demographic status, occupational exposure to biological agents as well as information on knowledge, awareness of PEP guidelines, attitude, and practice of the HCWs towards HIV PEP.

Results:

Of the 312 participants, 198 (63.5%) experienced an occupational injury, and 240 (76.9%) had a good attitude towards HIV PEP. Age, place of work, and inadequate knowledge were determinants of occupational exposure. Whereas, awareness of PEP guidelines and being a medical doctor influenced compliance with HIV PEP, with 158 (51.0%) having adequate knowledge of the guidelines. Out of the 198 who experienced occupational injury, 114 (57.6%) adopted the good practice and 60 (30.3%) made use of HIV PEP.

Conclusion and Global Health Implications:

Over half of health care workers had occupational exposure to HIV with poor utilization of post-exposure prophylaxis though they were aware and knowledgeable of PEP guidelines and exhibited good practice. Compliance with HIV PEP utilization was influenced by gender, awareness of PEP guidelines, and specialty of the health care worker.

Keywords

Occupational Exposure

Post-Exposure Prophylaxis

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Health Care Workers

1. Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is one of the main communicable diseases that has been a global challenge over the last 30 years.1 The HIV/AIDS pandemic marks a severe developmental crisis in Africa which remains by far the most affected region in the world.2 HIV/AIDs is a serious public health problem costing the lives of many people including health care workers (HCWs). According to a World Health Organization (WHO) report, an estimated 2.5% of HIV cases among HCWs worldwide were a result of occupational exposure due to accidental injuries at their work place3 as they are increasingly expected to provide care to people living with HIV infection (PLWHIV).

Health care workers are at an increased risk of contracting HIV after an occupational injury or exposure to infectious materials, such as blood, body tissue, body fluids, and contaminated environmental surfaces4 with 3/1000 injuries resulting in HIV transmission after percutaneous exposure from an HIV-infected patient in health settings.5 Percutaneous injury, usually inflicted by a hollow-bore needle, is the most common mechanism of occupational HIV transmission. Most people at risk of occupational exposure to HIV are in developing countries where there is a paucity of standard reporting protocols.6

The advent of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has started to reduce the global burden of HIV/AIDS with a decline in HIV cases. As such, the WHO recommended the use of HIV post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) in preventing the occurrence of HIV infection resulting from such accidental injuries at the workplace.7 PEP refers to the use of short-term antiretroviral drugs to reduce the risk of HIV acquisition following exposure.8 When administered shortly after being exposed, PEP treatment has been shown to reduce the risk of HIV infection by 81%.9 Hence, providing relevant information on HIV PEP for the health care professionals would help to identify unsafe practices, prevent the transmission of HIV and increase staff retention and productivity. However, studies have shown that there is an information gap in reporting occupational injury and the use of PEP in health care settings. A study in Ethiopia showed that 81.6% of exposed health care workers did not use PEP.10 Another study in Kenya also showed that only 45% of health care workers sought HIV PEP due to a lack of sufficient information11 while a study in Cameroon revealed a poor level of knowledge of HIV PEP among nurses (73.7%) in the Tubah health district of the northwest region of Cameroon.12

Cameroon bears one of the greatest burdens of HIV in West and Central Africa among adults aged 15-49 years.2 A study in Cameroon reported a 2.6% prevalence of HIV among HCWs.13 Although a few studies have assessed occupational exposure and knowledge on PEP for HIV among HCWs,12,14 there is very little data on the factors that influence the use of HIV PEP among health care workers after occupational exposure in Cameroon. Therefore, the main objective of this study is to determine the prevalence and determinants of occupational exposure to HIV, and the second objective is to identify factors that influence compliance to HIV post-exposure prophylaxis among HCWs in the Biyem-Assi, Buea, and Limbe Health Districts.

The study’s dependent variable was the prevalence of occupational exposure to HIV. The independent variables were determinants of occupational exposure (age of the participant, place of work, knowledge of HIV PEP and specialty) and factors that influence compliance to HIV PEP among study participants (awareness, knowledge, attitude, and practice).

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was a stratified cross-sectional study carried out from June to October 2019. Health care workers were randomly recruited from three Cameroonian Health Districts of Biyem-Assi, Buea, and Limbe. From the 3 Health Districts, 7 health institutions were included in the study: Biyem-assi District Hospital, Etoug-ebe Baptist Hospital, and Center Hospitalier et Universitaire (CHU)) from Biyem-assi Health District; Buea Regional Hospital, Buea Road Health Center from the Buea Health District; and Limbe Regional Hospital and Bota District hospital from the Limbe Health District.

2.2. Study Population and Sample Size Determination

HCWs from various clinical specialties in participating health care facilities were randomly recruited for the study. These professional groups comprised medical doctors, nurses, and medical laboratory technologists. The sample size of this study was calculated using the Lorentz formula:  where N= the minimum sample size, Z = Standard normal deviation (set at 1.96), P = Estimated proportion of 50% expected prevalence of HIV PEP use, D = Type 1 error, which was set at 0.05. From the calculation, the sample size N = {(1.96) ²x0.5x0.5}/(0.05)2 = 384. A total of 390 health care workers were recruited for the study.

where N= the minimum sample size, Z = Standard normal deviation (set at 1.96), P = Estimated proportion of 50% expected prevalence of HIV PEP use, D = Type 1 error, which was set at 0.05. From the calculation, the sample size N = {(1.96) ²x0.5x0.5}/(0.05)2 = 384. A total of 390 health care workers were recruited for the study.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

HCWs including medical doctors, nurses, and medical laboratory technologists who had been in close contact with patients and/or biological material (blood, urine, feces, etc.) for at least one year in the participating health care facilities were recruited for the study. The administrative staff of the health facilities or HCWs who had not spent up to one year in contact with patients were excluded from the study.

2.4. Data Collection

Data for this study were collected using a self-administered structured questionnaire. The questionnaire was adapted from Ulunma,15 Aminde et al.,16 and Bosena et al.10 A 26-item structured questionnaire included information on socio-demographic status (occupation, age, gender, and years of service in the health sector), occupational exposure to biological and chemical agents as well as information on knowledge, awareness of PEP guidelines, attitude and practice of the HCWs towards HIV PEP. Awareness of policies and procedures for reporting occupational accidents and PEP use were assessed using the universal PEP guidelines. Adequate knowledge was assessed from the awareness of the PEP guidelines, knowing when to initiate HIV PEP after occupational exposure, and the duration of use of drugs recommended for HIV PEP. The attitude was assessed from whether or not the respondent had a positive attitude towards HIV PEP, such as believing the guidelines are necessary, if the HIV PEP is reliable and if occupational exposure to biological agents through injuries can transmit HIV. Practice towards the HIV PEP protocol of each health institution was assessed through a visual check of the availability of the protocols pasted in each unit of the hospital and records on occupational exposure. The questionnaire was pretested on 30 participants at the Yaoundé Central Hospital of the Cite Verte Health District to ensure its consistency and reliability. Before administering the questionnaire, revisions were made based on feedback from the pretest.

2.5. Data Interpretation

A scoring system was used to assess participants’ awareness of the existence of PEP guidelines, knowledge, attitude, and practice toward HIV PEP. Awareness was assessed by asking participants about the existence of PEP guidelines in their health facility. Knowledge was categorized as adequate and inadequate. The knowledge of respondents about HIV PEP was assessed and respondents who scored greater than or equal to the mean score were considered to have adequate knowledge and respondents who scored less than the mean score were considered to have inadequate knowledge. Five questions were asked to assess participants’ attitudes towards PEP for HIV and the scores were categorized as positive, negative, or unsure. Those who scored 50% and above were considered as having a positive attitude while those below 50% were considered as having a bad attitude and those who were unsure of any of the five items were classified as unsure. The practice was considered only for participants who had experienced an occupational injury. To assess the practice of respondents who had experienced occupational injury, two questions were asked; “Did you report the injury?” and “did you screen for HIV after having reported the injury?” Respondents who answered “Yes” to both questions were considered as adopting good practice (complied) of PEP for HIV.

2.6. Data Analysis

Data generated from the questionnaire were entered into the Epi Collect 5 Software (Imperial College, United Kingdom) and exported to the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 26.0 software for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA). Data were collected using Epi Collect 5 software mobile version, wherein participants’ responses to the various questions in the questionnaire were captured. The data collected in the Epi Collect 5 software was exported into Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Washington, USA) and was cleaned (coded) in order to harmonize and prepare it for analysis. After cleaning and coding the data, descriptive statistics were employed to determine the frequency of study parameters and prevalence of occupational injury using SPSS version 26.0; these results were presented in tables and bar charts. Multiple logistic regression analysis was done to identify risk factors that are associated with occupational exposure to HIV and compliance to HIV PEP by determining the adjusted odds ratio. Differences with a p-value ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

2.7. Ethical and Administrative Consideration

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki (reviewed version of 2008) as well as local and national regulations in Cameroon. Ethical approval was obtained from the Faculty of Health Sciences Institutional Review Board of the University of Buea and from the Center Regional Ethical Committee board at the Yaoundé Regional Delegation of Public Health. After a careful explanation of the study aims and methods in the preferred language (English or French), written informed consent was obtained from participants before recruitment into the study. The study adhered to the standards of reporting wherein the data were kept confidential. Each participant was assigned a code and data were stored anonymously. The participants had no direct benefits from the study, nor any compensation for their participation.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographic Characteristics of Study Participants

Out of the 312 respondents, the majority were females 253 (81.1%). The overall mean age of the participants was 31.9 years with the most represented age group being the 19-29 age group (47.8%), followed by the 30-39 age group 106 (34.0%) and the least represented were those above 40 years of age 57 (18.3%). With regards to the type of health facility, the majority of the respondents 141 (45.2%) were staff of primary health facilities, 105 (33.7%) worked in tertiary health facilities, and 66 (21.2%) worked in secondary health facilities. The majority of participants 207 (66.3%) had between 1-5 years of clinical experience, followed by those with 6-10 years of experience 55 (17.6%), while, those above 10 years of experience 45 (14.4%) were the least. Among the respondents, the majority were nurses 209 (67.0%), followed by laboratory scientists 87 (27.9%) and medical doctors 16 (5.1%) the least (Table 1).

| Variable | Categories | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 253 | 81.1 |

| Male | 59 | 18.9 | |

| Age (Years) | 19-29 | 149 | 47.8 |

| 30-39 | 106 | 34.0 | |

| ≥ 40 | 57 | 18.3 | |

| Marital status | Married | 129 | 41.4 |

| Single | 176 | 56.4 | |

| Divorced | 2 | 0.6 | |

| Widow | 5 | 1.6 | |

| Type of health facility | Secondary hospital | 66 | 21.2 |

| Tertiary hospital | 105 | 33.7 | |

| Primary hospital | 141 | 45.2 | |

| Years of service | 1-5 | 207 | 66.3 |

| 6 – 10 | 55 | 17.6 | |

| ≥ 11 | 45 | 14.4 | |

| Specialty | Medical doctor | 16 | 5.1 |

| Nurse | 209 | 67.0 | |

| Laboratory technician | 87 | 27.9 | |

| Religion | Christian | 298 | 95.5 |

| Muslim | 10 | 3.2 | |

| Others | 4 | 1.3 | |

Objective 1: Prevalence and determinants of occupational exposure

3.2. Prevalence of Occupational Exposure to HIV

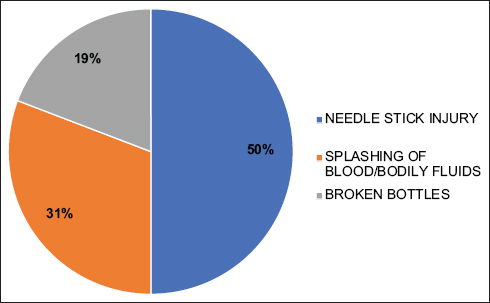

A total of 198 (63.5%) out of 312 of the HCWs had experienced an occupational injury at their health facility. Among them, 50% (99/198) suffered occupational exposures through needle stick injuries, followed by those exposed via splashing of blood or bodily fluids unto mucosal surfaces 30.8% (61/198) while the lowest were those exposed as a result of broken bottles 19.2% (38/198) (Figure 1). Among those who had needle stick injury, nurses were the most affected 64.6% (64/99), followed by laboratory technicians 29.3% (29/99), and medical doctors 6.1% (6/99) least. With regards to exposure to splashing of blood or bodily fluids onto mucosal surfaces, nurses were the most affected 70.5% (43/61), followed by laboratory technicians, 23.0% (14/61) while medical doctors suffered the least, 6.6% (4/61). Exposure through broken bottles was highest in nurses 89.5% (34/38) while 10.5% (4/38) were laboratory technicians. No medical doctor was exposed through this means (Figure 2).

- Prevalence of Occupational Injury Types Among Study Participants

- Prevalence of Occupational Injury Types Per the Participant’s Specialty

3.3. Determinants of Occupational Exposure to HIV

Multiple logistic regression analysis showed that HCWs aged between 30 and 39 years were 0.2 times more likely to be exposed (p<0.01) than their older counterparts. Workers in tertiary hospitals were 0.3 times more likely to be exposed (p<0.01) than those in reference hospitals. Also, health workers with inadequate knowledge of the PEP guideline were 0.5 times more likely to experience occupational exposure than those who had adequate knowledge of the guidelines. As such, age, place of work, and inadequate knowledge were factors that placed HCWs at risk of occupational exposure to HIV (Table 2).

| Determinant | N | Presence of Injury | Crude odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (%) | No (%) | ||||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 20-29 | 146 | 85 (58.2) | 61 (41.8) | 0.308 (0.084-1.124) | 0.075 |

| 30-39 | 106 | 81 (76.4) | 25 (23.6) | 0.199 (0.065-0.609) | 0.005* |

| ≥40 | 57 | 32 (56.1) | 25 (43.9) | Ref | |

| Subtotal | 309 | ||||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 58 | 36 (62.1) | 22 (37.9) | Ref | |

| Female | 251 | 162 (64.5) | 89 (35.5) | 1.193 (0.553-2.576) | 0.652 |

| Subtotal | 309 | ||||

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married/Cohabiting | 129 | 96 (74.4) | 33 (26.6) | 0.362 (0.029-4.588) | 0.433 |

| Single | 173 | 100 (57.8) | 73 (42.2) | 1.142 (0.087-15.045) | 0.920 |

| Divorce | 2 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | ||

| Widowed | 5 | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | Ref | |

| Subtotal | 309 | ||||

| Place of work | |||||

| Secondary Hospital | 64 | 32 (50.0) | 32 (50.0) | Ref | |

| Tertiary Hospital | 104 | 72 (69.2) | 32 (30.8) | 0.343 (0.156-0.750) | 0.007* |

| Primary Hospital | 141 | 94 (66.7) | 47 (33.3) | 0.487 (0.234-1.015) | 0.055 |

| Subtotal | 309 | ||||

| Duration in service (years) | |||||

| 1-9 | 204 | 125 (61.3) | 79 (38.7) | Ref | |

| 10-18 | 55 | 38 (69.1) | 17 (30.9) | 1.525 (0.577-4.030) | 0.395 |

| 19+ | 45 | 31 (68.1) | 14 (31.1) | 0.364 (0.091-1.446) | 0.151 |

| Subtotal | 304 | ||||

| Specialty | |||||

| Lab tech | 86 | 47 (54.7) | 39 (45.3) | Ref | |

| Medical Doctor | 16 | 10 (62.5) | 6 (37.5) | 0.568 (0.150-2.149) | 0.405 |

| Nurse | 207 | 141 (68.1) | 66 (31.9) | 0.854 (0.228-3.203) | 0.815 |

| Subtotal | 309 | ||||

| Knowledge | |||||

| Inadequate | 146 | 86 (58.9) | 60 (41.1) | 0.536 (0.288-1.000) | 0.050* |

| Adequate | 158 | 110 (69.6) | 48 (30.4) | Ref | |

| Subtotal | 304 | ||||

| Guideline awareness | |||||

| Yes | 253 | 167 (66.0) | 86 (34.0) | Ref | |

| No | 48 | 28 (58.3) | 20 (41.7) | 1.589 (0.711-3.548) | 0.259 |

| Subtotal | 301 | ||||

| Attitude | |||||

| Positive | 240 | 156 (65.0) | 84 (35.0) | Ref | |

| Negative | 37 | 20 (54.1) | 17 (45.9) | 1.426 (0.637-3.195) | 0.388 |

| Subtotal | 277 | ||||

Legend: χ2=Chi-square; Ref: Reference category;

Objective 2: Identification of factors that influence compliance to the use of HIV PEP

3.4. Awareness, Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice on HIV Post-exposure Prophylaxis

Results of participants’ awareness, knowledge, attitude, and practice as summarized in Table 2 were based on the participants having been exposed to some form of injury. Based on awareness of the HIV PEP guidelines out of 301 participants who responded to the questions on awareness, 253 (84.1%) participants acknowledged being aware of the guidelines, implying over 80% of participants knew that PEP should be started within 48 hours and no later than 72 hours following exposure, while a total of 48 (15.9%) were not aware of the guidelines. Among those aware of the guidelines (253), the majority were nurses (165), followed by laboratory technicians (75) and medical doctors (13). Although most HCWs were aware of the HIV PEP guidelines, some of them were not knowledgeable about the guidelines. Out of the 304 participants who responded to the questions on knowledge, 158 (52%) had adequate knowledge of the HIV PEP guidelines scoring above the mean score of 54%, while 146 (48.0%) had inadequate knowledge. Of the 158 HCWs who had adequate knowledge of HIV PEP guidelines, 106 (67.1%) were nurses, followed by laboratory technicians, 42 (26.6%) and the least were medical doctors, 10 (6.3%).

With regards to attitude, 277 participants responded to the questions. The majority of participants 240 (86.6%) had a positive attitude towards HIV PEP while 37 (13.4%) had a negative attitude. Among the respondents with a positive attitude, majority were nurses (158/240; 65.8%), followed by laboratory technicians (69/240; 28.7%) while (13/240; 5.4%) medical doctors were the least.

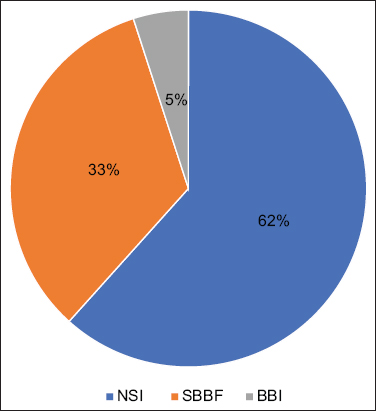

The practice of HIV PEP focused on conforming to the guidelines by respondents who had been exposed to injury by reporting the injury and/or screening for HIV as stated in the HIV PEP guidelines. Among the 198 study participants who had experienced an occupational injury, 114 (57.6%) reported the injury to the appropriate office and screened for HIV, while 84 (42.4%) did not report the injury or test for HIV (Table 3). Among the 84 participants that had poor practice, 34 (40.5%) did not report the injury because they tested negative for HIV, followed by 29 (34.5%) participants who thought it wasn’t necessary to report the injury, and 7 (8.3%) were not aware they needed to take HIV PEP. Among the 114 who had a good practice (reported their injury and/or screened for HIV), 60 (52.6%) sought HIV PEP treatment. Of these, the majority, 37 (62%) were exposed via needle stick injury, followed by respondents who had been exposed via splashing of blood/bodily fluids on mucosal surfaces 20 (33.3%) while 3 (5%) respondents were exposed via broken bottles (Figure 3).

| Factors | N | PEP Practice | Crude Odds Ratio(95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good (%) | Poor (%) | ||||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 20-29 | 85 | 38 (44.7) | 47 (55.3) | Ref | |

| 31-39 | 81 | 56 (77.0) | 25 (23.0) | 0.394 (0.147-1.051) | 0.063 |

| ≥40 | 32 | 20 (62.5) | 12 (37.5) | 0.755 (0.126-4.519) | 0.759 |

| Subtotal | 198 | ||||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 36 | 16 (44.4) | 20 (56.6) | 0.344 (0.125-0.950) | 0.039* |

| Female | 162 | 98 (60.5) | 64 (39.5) | Ref | |

| Subtotal | 198 | ||||

| Marital Status | |||||

| M/C | 96 | 61 (63.5) | 35 (36.5) | Ref | |

| Single | 100 | 52 (52.0) | 48 (48.0) | 1.50 (0.618-3.642) | 0.370 |

| Widowed | 2 | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 4.13 (0.199-85.663) | 0.359 |

| Subtotal | 198 | ||||

| Religion | |||||

| Christian | 191 | 113 (59.2) | 78 (40.8) | 0.215 (0.016-2.873) | 0.245 |

| Muslim | 6 | 1 (16.7) | 5 (83.3) | Ref | |

| Subtotal | 197 | ||||

| Place of work | |||||

| Secondary Hospital | 32 | 19 (59.4) | 13 (40.6) | 0.757 (0.271-2.110) | 0.594 |

| Tertiary Hospital | 72 | 41 (56.9) | 31 (43.1) | 0.549 (0.239-1.260) | 0.157 |

| Primary Hospital | 94 | 54 (57.4) | 40 (43.6) | Ref | |

| Subtotal | 198 | ||||

| Duration in service (years) | |||||

| 1-9 | 125 | 67 (53.6) | 58 (46.5) | Ref | |

| 10-18 | 38 | 25 (65.8) | 13 (34.2) | 1.270 (0.379-4.259) | 0.698 |

| 19+ | 31 | 21 (67.7) | 10 (23.3) | 0.796 (0.148-4.282) | 0.791 |

| Subtotal | 194 | ||||

| Specialty | |||||

| Lab tech | 47 | 35 (74.5) | 12 (25.5) | 0.975 (0.155-6.134) | 0.979 |

| Medical Doctor | 10 | 6 (60.0) | 4 (40.0) | 4.496 (1.762-11.469) | 0.002* |

| Nurse | 141 | 73 (51.8) | 68 (48.2) | Ref | |

| Subtotal | 198 | ||||

| Knowledge | |||||

| Inadequate | 86 | 41 (47.7) | 45 (52.3) | Ref | |

| Adequate | 110 | 71 (64.5) | 39 (35.5) | 0.937 (0.405-2.169) | 0.879 |

| Guideline Awareness | |||||

| Yes | 167 | 103 (61.7) | 64 (38.3) | 4.018 (1.199-13.460) | 0.024* |

| No | 28 | 8 (28.6) | 20 (71.4) | Ref | |

| Subtotal | 195 | ||||

| Attitude | |||||

| Positive | 156 | 96 (61.5) | 60 (38.5) | 1.942 (0.646-5.838) | 0.237 |

| Negative | 20 | 9 45.0) | 11 (55.0) | Ref | |

| Subtotal | 176 | ||||

Notes: χ2=Chi-square; M/C: Married/Cohabiting; Ref: Reference category; β = regression coefficient;

- Compliance with Post-Exposure Prophylaxis as Per Injury Type Notes: NSI=needle stick injury; SBBF=splashing of blood/bodily fluids; BBI=broken bottle injury

A multiple logistic regression analysis showed that medical doctors were 4.4 times more likely to comply with the good practices that guide the use of HIV PEP than nurses. Health care workers who were aware of the HIV PEP guideline were 4 times more likely to comply with the good practices of HIV PEP use. Male health care workers were 0.3 times less likely to comply with the good practices of HIV PEP use. Thus, specialty (medical doctor) and having awareness of the PEP guideline favored compliance with HIV PEP use while male health workers were less likely to comply with HIV PEP use (Table 3).

4. Discussion

This study investigated the prevalence and determinants of occupational exposure to HIV infection and identified factors that influenced compliance to the use of HIV PEP among HCWs in Cameroon, where limited information is available. Occupational exposure to HIV in HCWs is of public health concern in Cameroon, a country with an elevated burden of HIV within the central African region.2 Occupational injuries expose HCWs to HIV infection and other blood-borne infections in a hospital setting while providing care to an infected patient.

Our findings showed that over half of the health care workers (63.5%) had suffered occupational injuries. This prevalence is higher than reported in a previous study in Cameroon which recorded a 50.9% prevalence of occupational injury14 as well as a study in Tanzania which recorded a prevalence of 50.6%.17 This finding suggests that there is increased negligence and failure by the HCWs to adhere to the universal precaution thereby implementing unsafe practices in health care settings in Cameroon. Among the type of occupational injuries incurred by HCWs, needle stick injury was the most prevalent with 40.9%, followed by the splashing of blood/bodily fluids on mucosal surfaces (21.2%). This finding contradicts a study in Tanzania wherein splashing of blood/bodily fluids on mucosal surfaces was the most prevalent occupational injury incurred by HCWs followed by needle stick injuries.17 The high prevalence of needle stick injuries could be a result of the constant and continuous use of syringes in the administration of drugs and collection of blood, recapping of the needle after use on the patients as has been previously reported.17 Needle stick injuries of health care workers are an important occupational hazard leading to infections with bloodborne pathogens like HBV, HCV, or HIV.18

Findings from this study showed the place of work, especially secondary health facilities (p = 0.007) and inadequate knowledge of HIV PEP guidelines (p = 0.050) are factors that place HCWs at risk of occupational exposure to HIV. This finding is contrary to the findings of a study carried out in the Western Cape of South Africa, where there were no significant associations between occupational exposure to HIV and sociodemographic characteristics.19 Our findings are also contrary to the report of a study carried out in southeast Ethiopia where HCWs working in general and referral hospitals were less likely to experience occupational exposures.20

Following the increasing prevalence of occupational exposure to HIV among HCWs, the WHO recommended guidelines for the use of PEP which entails reporting the injury, and testing for HIV before receiving PEP no later than 72 hours following exposure which is considered a good practice.21 However, some of the major drawbacks of the implementation have been the lack of knowledge and awareness of the HIV PEP guidelines by HCWs.12 Findings from this study showed that the majority of the HCWs (81.7%) acknowledged being aware of the PEP guidelines while only about half of them (51%) had adequate knowledge of the guidelines. This finding corroborates with the findings of a study in Ghana22 and another in South Africa23 where half of the participants were knowledgeable of the PEP guidelines. A higher proportion of participants in our study were knowledgeable of PEP guidelines than in a study in the Fako Division of Cameroon, where 58% of the study participants had poor knowledge of PEP.14 A considerable number of respondents were aware that injuries such as needle pricks, and splashes of blood/bodily fluids onto mucosal surfaces could result in HIV infection. Also, over 80% of participants knew that PEP should be started within 48 hours and no later than 72 hours following exposure. A good number of respondents didn’t know the appropriate drug regimen for HIV PEP. A high percentage of the HCWs (77.2%) had a positive attitude about PEP as they believed it reduces the transmission of HIV following exposure. Among the 137 HCWs who had experienced some form of injury, most of them (64.6%) exhibited good practice for the implementation of the HIV PEP guidelines as they either reported the injury to the appropriate office and/or screened for HIV. Of the 198 respondents who reported injuries, 60 (30.3%) utilized HIV PEP. The level of PEP utilization following occupational exposure in our study is lower than that of a study carried out in Botswana where 53.7% of the HCWs used PEP following exposure.24

The use of PEP among HCWs in developing countries is still low compared to developed countries.25 Some studies have shown that inadequate knowledge of PEP26,27 and the fear of possible HIV-positive results and its associated stigma among other reasons are responsible for the low use of PEP.2 Although the low use of PEP by HCWs in this study remains unclear, however, certain factors might have influenced compliance with HIV PEP in this study. Findings from this study show that medical doctors (p = 0.002) and health care workers who are aware of the PEP guidelines (p = 0.024) were likely to comply with the use of HIV PEP, while male participants were less likely to comply (p = 0.039). These findings suggest that awareness of the PEP guidelines, being a woman, and being a medical doctor are three key factors that influenced the use of PEP following exposure due to occupational injury.

Although this study strictly adhered to standard methods of data collection using a questionnaire, it was limited in that it relied on subjective recall by participants and thus may have suffered from recall bias resulting either in over or under-reporting of information. Also, some participants did not respond to some of the questions. This affected the response rate of the study and may have affected the overall outcome of the study.

5. Conclusion and Global Health Implications

This study shows that over half of health care workers had occupational exposure to HIV with poor utilization of post-exposure prophylaxis though they were aware and knowledgeable of PEP guidelines and exhibited good practice. Compliance with HIV PEP utilization was influenced by gender, awareness of PEP guidelines, and the specialty of health care workers. The high level of occupational exposure to HIV and low level of PEP use among health care workers underscores the need for capacity strengthening through in-service training and structured intervention for health care workers on accidental exposure to HIV and use of PEP.

Acknowledgments:

The authors are grateful to all who took part in this study.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Financial Disclosure: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval for the study was sought from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Buea, and the Center Regional Ethics Committee for Human Health Research of the Center Region, Cameroon.

Disclaimer: None.

References

- Assessment of the knowledge and attitudes regarding HIV/AIDS among pre-clinical medical students in Israel. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7(1):168. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-7-168

- [Google Scholar]

- AIDS-and sexuality-related stigmas underlying the use of post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV in Brazil:findings from a multicentric study. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2019;27(3):1650587. doi:10.1080/26410397.2019.1650587

- [Google Scholar]

- Reducing Risks, Promoting Healthy Life. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002.

- Occupational exposure to blood and body fluids and use of human immunodeficiency virus post-exposure prophylaxis amongst nurses in a Gauteng province hospital. Health SA. 2020;25(1):1252. doi:10.4102/hsag.v25i0.1252

- [Google Scholar]

- Notes from the field:occupationally acquired HIV infection among health care workers—United States, 1985–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;63(53):1245-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Estimation of the global burden of disease attributable to contaminated sharps injuries among health-care workers. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48(6):482-90. doi:10.1002/ajim.20230

- [Google Scholar]

- Post-Exposure Prophylaxis to Prevent HIV Infection:Joint WHO/ILO guidelines on post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) to Prevent HIV Infection. Geneva: World Health OrganizationHealth Organization; 2007.

- Current perspectives in HIV post-exposure prophylaxis. HIV/AIDS (Auckl). 2014;6:147-58. doi:10.2147/HIV. S46585

- [Google Scholar]

- Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) in South Africa:Analysis of calls to the national AIDS help line. 2019. Cadre. www.cadre.org.za

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of HIV post-exposure prophylaxis use among health workers of governmental health institutions in Jimma Zone, Oromiya Region, Southwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2010;20(1):55-64. doi:10.4314/ejhs.v20i1.69429

- [Google Scholar]

- The preexposure prophylaxis revolution;from clinical trials to programmatic implementation. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2016;11(1):80-6. doi:10.1097/COH.0000000000000224

- [Google Scholar]

- Occupational post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in a health district in Cameroon:Assessment of the knowledge and practices of nurses. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0124416. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0124416

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and risk factors to HIV-infection amongst health care workers within public and private health facilities in Cameroon. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;29(1):158. doi:10.11604/pamj.2018.29.158.14073

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of the knowledge, attitude and practice of health care workers in Fako Division on post exposure prophylaxis to blood borne viruses:a hospital based cross-sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;31(1):108. doi:10.11604/pamj.2018.31.108.15658

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors Impacting HIV Post Exposure Prophylaxis among Health Care Workers Dissertation. Walden University. ;2017:94-98.

- [Google Scholar]

- Occupational post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) against human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection in a health district in Cameroon:assessment of the knowledge and practices of nurses. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0124416. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0124416

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of occupational injuries and knowledge of availability and utilization of post exposure prophylaxis among health care workers in Singida District Council, Singida Region, Tanzania. PloS One. 2018;13(10):e0201695. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0201695

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and prevention of needle stick injuries among health care workers in a German university hospital. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2008;81(3):347-54. doi:10.1007/s00420-007-0219-7

- [Google Scholar]

- Occupational exposure to HIV among nurses at a major tertiary hospital:Reporting and utilization of post-exposure prophylaxis:a cross-sectional study in the Western Cape, South Africa. PloS One. 2020;15(4):e0230075. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0230075

- [Google Scholar]

- Practices of healthcare workers regarding infection prevention in bale zone hospitals, southeast Ethiopia. Adv Public Health 2020 doi:10.1155/2020/4198081

- [Google Scholar]

- Adherence to HIV post-exposure prophylaxis for children/adolescents who have been sexually assaulted:a systematic review of barriers, enablers, and interventions. Child Abuse Negl. 2021;116(1):104143. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104143

- [Google Scholar]

- Determinants of Post Exposure Prophylaxis Uptake Following Occupational Exposure to HIV in Matabeleland South Province. In: Dissertation. University of Zimbabwe; 2018.

- [Google Scholar]

- Occupational exposure to HIV among nurses at a major tertiary hospital:reporting and utilization of post-exposure prophylaxis:a cross-sectional study in the Western Cape, South Africa. PloS One. 2020;15(4):e0230075. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0230075

- [Google Scholar]

- Protection for sale:an empirical investigation. Am Econ Rev. 1999;89(5):1135-55. doi:10.1257/aer.89.5.1135

- [Google Scholar]

- Post exposure prophylaxis following occupational exposure to HIV:a survey of health care workers in Mbeya, Tanzania,2009-2010. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;21(1):32. doi:10.11604/pamj.2015.21.32.4996

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of knowledge, attitudes and practices of HIV post exposure prophylaxis among the doctors and nurses in Princess Marina Hospital, Gaborone:a cross-sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;30(1):233. doi:10.11604/pamj.2018.30.233.10556

- [Google Scholar]