Translate this page into:

Fatal Cases of Gestational Trophoblastic Neoplasia in a National Trophoblastic Disease Reference Center in Dakar Senegal

*Corresponding author email: mamourmb@yahoo.fr

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Objectives:

The objectives of this study were to analyze deaths after gestational trophoblastic neoplasia and to determine the factors of treatment failure.

Methods:

This is a retrospective study in Aristide Le Dantec teaching Hospital in Dakar, Senegal, between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2014. We took into account socio-epidemiological characteristics of patients, initial diagnosis, time between uterine evacuation and admission, time to onset of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN), treatment received (deadlines, protocols), difficulties experienced in the diagnosis and the initiation of treatment and survival.

Results:

In total, 1044 patients were admitted during the study period; 164 cases of GTN were diagnosed (15.7%); and 21 deaths occurred leading to a specific lethality of 12.8%. The average age was 30 years. Almost all patients (n = 18; 85.7%) had low income or no income. Eight out of 21 patients (38.1%) were seen in our department after GTN onset. The mean time to onset of GTN of all patients was 22.1 weeks. For 66.6%, histology was not available; the diagnosis of hydatidiform mole was made on the clinical history and sonographic features and GTN on human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) evolution and ultrasound findings. None of the patients had regular chemotherapy due to financial reasons. Patients who died within 3 months after diagnosis had metastatic tumors (7 of 21). All these women had resistance to treatment or progressed after three courses of chemotherapy. Ten of the 12 women with high-risk GTN were not treated with multi-agent chemotherapy (EMA-CO) for purely financial reasons.

Conclusion and Global Health Implications:

The high incidence and mortality require a profound reorganization of our health system and a high awareness of practitioners to refer to time or to declare all suspected cases of hydatidiform mole or gestational trophoblastic neoplasia.

Keywords

Gestational

Trophoblastic Neoplasia

GTN

Outcome

Death

Senegal

Introduction

Gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD) encompasses a spectrum of pregnancy-related disorders that includes benign, pre-malignant disorders (complete and partial hydatidiform mole), and persistent, malignant disorders (invasive mole, choriocarcinoma, placental site trophoblastic tumor and epithelial trophoblastic tumor). Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) is a term used for the persistent/malignant disorders.[1] All these pathologies derive from trophoblast and differ in their propensity in invasion (local or general) or spontaneous resolution. Most women with molar pregnancy can be cured by removal of the products of conception and fertility is preserved.[2]

The incidence of hydatiform mole in Senegal is 1/400 pregnancies.[3] In some cases, the growth continues, and gestational trophoblastic tumor (GTT) or gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) occurs. It is a malignant form of the disease that requires chemotherapy.[4] Patients with gestational trophoblastic neoplasia are categorized into low and high risk according to the International Federation of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians (FIGO).[5] This risk categorization refers to the resistance to methotrexate. The prognosis depends largely on early diagnosis and the start of chemotherapy adapted to the 2000 FIGO score.[5] Treatment of low-risk GTN aims at 100% of complete remission. Single-agent chemotherapy is achieved by the combination of methotrexate and folinic acid or using Dactinomycin. The first-line treatment of high-risk GTN is multi-agent chemotherapy using EMA-CO (Etpososide – Methotrexate-Actinomycine D- Cyclophosphamide-Oncovin). Treatment failure reasons are often known as a delay in diagnosis, care and drug resistance.[6] In Africa, particularly in Senegal, patients are often seen late.[7] The thorny problem of the management still remains. Therefore, the aim of this study was to analyze the deaths after gestational trophoblastic neoplasia to determine treatment failure factors.

Methods

This is a retrospective study of patients with gestational trophoblastic neoplasia diagnosed and supported at the Obstetric and Gynecologic Clinic at Dakar teaching hospital between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2014. Our department is the National Reference Centre of Gestational Trophoblastic Diseases.

We took into account socio-epidemiological characteristics of patients, initial diagnosis, time between uterine evacuation and admission, time to onset of GTN, treatment (deadlines, protocols), difficulties encountered in the implementation of therapy and survival.

Post-care abortion and deliveries are not supported in our center. All patients were initially supported in other health centers for uterine evacuation and referred to our center for monitoring.

Usage of 2000 FIGO score in our department began in 2011. FIGO staging and scoring system are detailed in Tables 1 and 2. For patients admitted before that date, we tried to assess risk based on information available in the files.

| Stage I | Disease confined to the uterus |

| Stage II | GTN extends outside of the uterus, but is limited to the genital structures (adnexa, vagina, broad ligament) |

| Stage III | GTN extends to the lungs, with or without known genital tract involvement |

| Stage IV | All other metastatic sites |

| Scores | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | <40 | ≥40 | ||

| Antecedent pregnancy | Mole | Abortion | Term | |

| Antecedent pregnancy from index pregnancy | <4 | 4-6 | 7-12 | ≥13 |

| Pre-treatment serum hCG (UI/ml) | <103 | 103-<104 | 104-<105 | ≥105 |

| Largest tumor size (including uterus | 3-<5cm | ≥5cm | ||

| Site of metastasis | Lung | Spleen, kidney | Gastro-intestinal | Liver, Brain |

| Number of metastases | 0 | 1-4 | 5-8 | >8 |

| Previous failed chemotherapy | Single drug | 2 or more drugs | ||

Score-6: Low-risk group Score-7: High-risk group

From that date, chemotherapy with Methotrexate every 14 days was prescribed for patients at low risk. For patients with a score greater than or equal to 7, multi-agent chemotherapy (EMA-CO) was proposed. It was performed if the patient and her family could obtain drugs. Otherwise, a chemotherapy combining various drugs was proposed and administered: Etoposide-Cisplatin, Etoposide Endoxan-Methotrexate, Methotrexate -5FU-Etoposide. This study focuses on 21 cases of death. Data were entered and analyzed using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Science) 19.0. Survival curves were performed using the Kaplan-Meier method.

Results

Frequency

In total, 1044 patients were admitted during the study period, 164 cases (15.7%) of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) were diagnosed and 21 deaths occurred leading to a specific lethality of 12.8% (21/164).

Characteristics of patients

The average age was 30 years with a low of 16 and high of 54 years and the average parity, 3 (range 0 to 10). Almost all patients (n = 18; 85.7%) had low income or any income.

The average time between the initial evacuation of hydatidiform mole and the first contact was 3.6 months.

Diagnosis and treatment

Eight of 21 patients (38.1%) were seen in our department beyond 2 months after uterine evacuation. The mean time to onset of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia was 22.1 weeks (5.5 months). In 71.7% of patients, histology was not carried out after initial uterine evacuation, the diagnosis of hydatidiform mole was made on clinical and ultrasound features and that of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia on history, evolution of human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) and ultrasound findings. Patient’s characteristics are summarized in Table 3.

| Variables | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Income | ||

| Low | 12 | 57,1 |

| None | 6 | 28,6 |

| Middle | 3 | 14,3 |

| Uterine evacuation-contact (months) | ||

| <1 | 8 | 38,8 |

| 1-2 | 4 | 18,8 |

| 3-4 | 3 | 14,2 |

| 5-6 | 2 | 9,4 |

| ≥7 | 4 | 18,8 |

| Histology | ||

| Complete hydatiform mole | 1 | 4,7 |

| Partial hydatiform mole | 2 | 9,4 |

| Choriocarcinoma | 3 | 14,2 |

| Unknown | 15 | 71,7 |

None of the patients had regular chemotherapy. Instead of a cycle of methotrexate every 14 days, the average time between cycles was 4 weeks. Some patients took a break after two cycles and came back after collecting the amount needed to buy drugs and continue treatment. The single-agent chemotherapy cycle with Methotrexate is financially estimated between CFA 35,000 and CFA 42,000 ($50 and $60) (folinic acid excluded). For multi-agent chemotherapy using EMACO (Etoposide, Methotrexate, dactimomycine, cyclophosphamide and vincristine), CFA 250,000 ($355) were needed per cycle. This protocol was hardly implemented. It was given to only 3 out of the 21 patients in the study. Patient’s diagnostic and therapeutic characteristics are summarized in Table 4

| Cases | hCG before treatment (IU/l) | Year | Age (years) | Time to onset of GTN | Surgery | Chemotherapy | Number of cycle | Cycle regularity | 2000 FIGO score | Survival (months) | Metastasis site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Unspecified | 2007 | 16 | - | - | MTX-Cyclophosphamide | 4 | Now | HR* | 1,83 | |

| 2 | Unspecified | 2007 | 43 | 21,43 | - | MTX-Cyclophosphamide | 4 | Now | HR* | 0,67 | |

| 3 | 13443 | 2007 | 30 | 141,71 | - | MTX-Cyclophosphamide | 3 | Now | HR* | 1,30 | |

| 4 | 2213 | 2007 | 54 | 0,00 | HTR | - | - | - | HR* | 1,40 | |

| 5 | 159290 | 2008 | 21 | 13,14 | - | MTX/Etoposide Cisplatine | 4/1 | Now | HR* | 0,87 | Brain |

| 6 | 48568 | 2008 | 21 | 0,71 | - | MTX-Cyclophosphamide | 23 | Now | LR* | 26,80 | Genital tract |

| 7 | 285 | 2009 | 23 | 80,86 | HTR | MTX-Cyclophosphamide | 19 | Now | HR* | 15,07 | Brain |

| 8 | 255 | 2009 | 40 | 2,14 | HTR | MTX-Cyclophosphamide/EMACO | 7/1 | Now | HR* | 23,83 | Liver, Lung |

| 9 | 170 | 2010 | 30 | 40,14 | - | MTX-Cyclophosphamide/5FUMTXVP16 | 13/3 | Now | HR* | 2,27 | |

| 10 | 75 | 2010 | 30 | 42,86 | - | MTX-Cyclophosphamide/MTX/Etoposide | 9/3/2 | Now | LR* | 19,33 | |

| 11 | Unspecified | 2010 | 24 | - | - | MTX-Cyclophosphamide | 7 | Now | LR* | 36,97 | |

| 12 | 54654 | 2011 | 44 | 35,86 | HTR | MTX-Cyclophosphamide | 8 | Now | LR | 11,23 | |

| 13 | 47674 | 2011 | 27 | 3,14 | - | None | - | - | BR | 1,40 | |

| 14 | 33535 | 2012 | 28 | 5,71 | HTR | MTX/5FU-MTX-VP16 | 2/1 | Now | BR | 2,87 | |

| 15 | 10000 | 2012 | 40 | 0,71 | - | MTX-Cyclophosphamide | 2 | Now | BR | 2,67 | |

| 16 | 32836 | 2012 | 27 | 5,86 | HTR | MTX/EMACO | 7/1 | HR | 23,20 | Brain, Liver | |

| 17 | 114406 | 2012 | 19 | 29,43 | - | MTX | HR | 10,43 | |||

| 18 | 1298316 | 2013 | 23 | 27,71 | - | None | - | - | HR | 2,33 | Liver |

| 19 | 140168 | 2013 | 41 | 6,29 | - | MTX | 2 | Now | LR | 10,73 | |

| 20 | 208829,41 | 2013 | 21 | 104,71 | - | 5FU-MTX-VP16 | 2 | Now | HR | 1,67 | Brain, Liver |

| 21 | 191639 | 2013 | 28 | 51,71 | HTR | EMACO | 3 | HR | 11,00 | Lung | |

LR: Low risk, HR: High risk, MTX: Methotrexate, 5FU: 5 Fluoro-Uracile, VP16: Etoposide, EMACO: Etoposide, Methotrexate, Dactinomycine, Cyclophosphamide, Oncovin, HTR: Hysterectomy,

Seven out of 21 patients who were deceased within 3 months after diagnosis had metastatic tumors. All these women had resistance to treatment or progression.

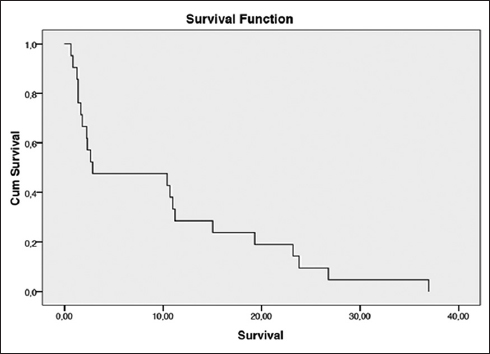

Patients who were at low risk with relatively long survival (n=3) had begun their treatment and stopped it. They were readmitted in a very bad condition. An exploration of the achievement of the disease was not carried out for financial reasons. Moreover, they could not benefit from chemotherapy because of their overall condition. In all, 10 of the 12 women at high risk according to FIGO did not receive multi-agent chemotherapy (EMA-CO) for exclusively financial reasons. The average survival time was 9.9 months ([95% CI] 5.369-14.429) and the median was 2.87 months ([95% CI] 0.000-14.982) as shown in Figure 1.

- Survival curve using Kaplan-Meier method

Discussion

The FIGO Oncology Committee at its meeting during the XXVI FIGO World Congress of Gynecology and Obstetrics in Washington DC in September 2000 revised the staging system of Gestational Trophoblastic Neoplasia (GTN).[1] The following criteria were retained:

GTN may be diagnosed when the plateau of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) lasts for four measurements over a period of 3 weeks or longer; that is, days 1, 7, 14, 21.

GTN may be diagnosed when there is a rise of hCG of three weekly consecutive measurements or longer, over at least a period of 2 weeks or more; days 1, 7, 14.

GTN is diagnosed when the hCG level remains elevated for 6 months or more.

GTN is diagnosed if there is a histologic diagnosis of choriocarcinoma.

Two points are capital: the diagnosis of GTN must be early because it has prognostic influence; the treatment must be appropriate, treating the real early gestational trophoblastic neoplasia by validated chemotherapy protocols. The aim of treatment of low risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia is to obtain a complete cure. Chemotherapy with methotrexate leads to 90.2% remission in stage I and 68.2% for stage II and III.[8] Sekharan et al. found a complete response rate of 93% on a series of 321 patients.[4] Gestational trophoblastic tumors at high risk should be treated immediately by multi-agent chemotherapy. EMA-CO protocol is considered to be the standard of care. The EMACO protocol results in complete remission up to 100% in high-risk stage II and between 76 and 97.3% in higher stages and metastatic conditions.[9] The second line treatment is EP-EMA (Etoposide-Cisplatin/Etoposide Methotrexate, dactinomycin), which provides 70-76% remission after failure of first-line chemotherapy with EMA-CO.[2,4]

Criteria for the diagnosis of trophoblastic neoplasia are used in our department since 2011; chemotherapy protocols are also recommended by level of risk. But the administration of some chemotherapy regimens was motivated by inaccessibility to standard protocols.

The particularity of our health system is the lack of health insurance. Although some tests are supported, chemotherapy drugs are in charge of patients and their families. The income level of the couples was very low. This situation leads to lack of normal monitoring of hCG which delays the diagnosis of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia and worsens the prognosis of these patients.

Chemotherapy adapted to low-risk FIGO score is estimated between CFA 35,000 ($50) and CFA 42,000 ($60) per cycle. Patients and their families cannot always gather this amount. We rarely prescribe folinic acid in “rescue;” a bottle of folinic acid costing more than the Methotrexate cycle. Fortunately, we rarely observe side-effects associated with methotrexate.

A cycle of EM-ACO protocol (d1, d2 and d8) is financially valued at CFA 250,000 ($355). This represents more than the average wage of a Senegalese worker. The problem is much deeper and the solution is not at an individual level. It requires a profound reorganization of the health system. We cannot hope for cancer convincing results if drugs are in charge of patients. This inequity in care is our daily challenge both in the treatment of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia and in other cancers such as breast cancer. We have developed several social strategies to address this situation. Indeed, a social worker in our department regularly approaches some persons who accept willingly to sponsor some patients. But the treatment is long and expensive; this approach has also shown the limits of its efficiency.

Patients with short survival had already gestational trophoblastic neoplasia when admitted in our department, several months after uterine evacuation. The upstream monitoring was not properly insured. On admission, they had visceral metastases. Unable to achieve the chemotherapy drugs appropriate to the risk, there have been prescribed a protocol adapted to their means or no protocol at all. Sometimes their general condition did not allow the start of chemotherapy until death occurs.

Conclusion and global health implications

This sad situation is a daily occurrence and requires a deep reorganization of our health system and a high awareness of practitioners to refer to time or declare all suspected cases of hydatidiform mole or gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. We cannot hope for cancer convincing results if drugs are in charge of patients. Our Center plans to organize training to practitioners in order to harmonize practices. A more ambitious free treatment plan of gestational trophoblastic diseases is being prepared. It will be presented to the authorities of the Ministry of Health.

Ethical considerations: This study was approved by the Dakar Teaching Hospital and the National Reference Centre of Gestational Trophoblastic Diseases.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Prise en charge d’une tumeur trophoblastique gestationnelle. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2010;38:193-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prediction of persistent gestational trophobalstic neoplasia: The role of hCG level and ratio in 2 weeks after evacuation of complete mole. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124(250-3)

- [Google Scholar]

- Etude ultrastructurale de la môle hydatiforme au Sénégal: données préliminaires. Revue Française de Gynécologie et d’Obstétrique. 1999;95(5):409-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gestational trophoblastic disease: current management of hydatidiform mole. BMJ. 2008;337:1193.

- [Google Scholar]

- FIGO staging for gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;77:285-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outcome of molar pregnancy at Dakar teaching hospital. International Journal of Maternal and Child Health. 2013;1(4):63-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Current management of gestational trophoblastic diseases. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112(3):654-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Subsequent pregnancy outcome, including repeat molar pregnancy. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 1998;43:81-6.

- [Google Scholar]