Translate this page into:

Addressing Global Health, Development, and Social Inequalities through Research and Policy Analyses: The International Journal of MCH and AIDS

Almost one year ago, we were on a lunchtime walk in the outskirts of the nation's capital, Washington, DC. Amidst the ruffles of dry leaves, the birds chirruped. Some lawn mowers vibrated as they chewed grasses in this usually quiet neighborhood. As is the unwritten ‘rule’ for our walks, we joked, we talked about our current projects, our planned work, and the opportunities and the challenges for the future. On this rather chilly day, our discussion somehow veered into how we both can utilize our successful careers to benefit our global ancestry. We had spent our early years in developing countries: Gopal in India, Asia and Romuladus in Nigeria, Africa. As this discussion unveiled, we saw a synchronous passion to give back not only to Asia and Africa but also to the entire developing countries. A few projects came up. After weighing the pros and cons, the idea of the International Journal of MCH and AIDS (IJMA) was preeminent. We agreed that IJMA was a fertile ground to cultivate a global intellectual coalition to highlight the issues in the hinterlands of developing countries and to offer a platform to offer practical policy suggestions to address these issues. Above all, IJMA's idea went beyond the usual talk about “giving back.” The idea was laden with action.

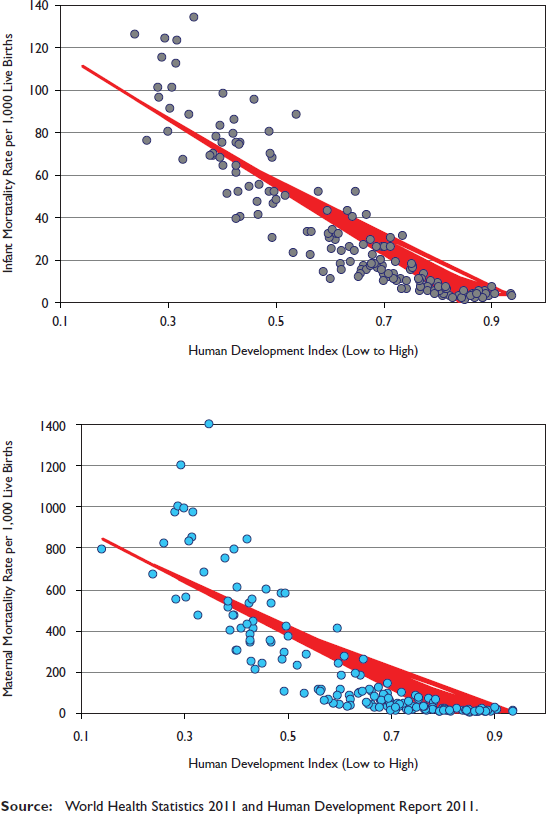

One year after this lunchtime walk and the birth of IJMA, we continue to share the passion to document, and shine the light on the myriads of global health issues that debilitate developing countries. Although the focus of IJMA is on the social determinants of health and disease as well as on the disparities in the burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases affecting infants, children, women, adults, and families in developing countries, we would like to encourage our fellow researchers and policy makers in both the developing and developed countries to consider submitting work that examines cross-national variations in heath and social inequalities. Such a global focus allows us to identify and understand social, structural, developmental, and health policy determinants underlying health inequalities between nations[1,2]. Global assessment of health and socioeconomic patterns reaffirms the role of broader societal-level factors such as human development, gender inequality, gross national product, income inequality, and healthcare infrastructure as the fundamental determinants of health inequalities between nations. This is also confirmed by our analysis of the WHO data in Figure 1 that shows a strong negative association between levels of human development and infant and maternal mortality rates (γ > -0.85)[3].

- Relationship between Human Development Index and Infant and Maternal Mortality Rates, 167 Countries, 2008-2010

Focusing on socioeconomic, demographic, and geographical inequalities within a developing country, on the other hand, should give us a sense of how big the problem of health inequity is within its own borders. Such an assessment, then, could lead to development of policy solutions to tackle health inequalities that are unique to that country[2].

The papers in this inaugural issue—among the best you can get in any journal of its ilk—bail us out. In their commentary, Hairston and experts from the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation (EGPAF) make the case for the integration of maternal, sexual, and reproductive health services as a foundation for eliminating pediatric HIV in developing countries[4]. While the newly-launched UN Global Plan Towards Elimination of New HIV Infections renews the momentum around the elimination of pediatric HIV, it presents a unique opportunity to place women at its center by linking research, policies, and programs to sexual reproductive and maternal health, writes the experts. They call on stakeholders to utilize the synergies between HIV and sexual and reproductive health programs to address the diverse health needs of women and in eventually eliminating pediatric HIV worldwide[4]. As the leading non-profit organization in the field of MCH and HIV/AIDS, a substantive presence in developing countries, and an A rating from US CharityWatch, no other organization understands HIV/AIDS and MCH in developing countries better than EGPAF. And their counsel must be taken seriously.

In their article on global inequalities in cervical cancer, Singh and colleagues look at global disparities in cervical cancer, which is not only a major public health problem in many low-and middle-income countries but is also the number one cancer site and a major killer of women in reproductive ages in East and Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia[5]. They go on to show that inequalities in cervical cancer rates among 184 countries are strongly linked to disparities in human development, social inequality, and living standards and argue for improvements in women's social status and wider availability of preventive cancer screening services as the primary means to achieving reductions in cervical cancer rates[5].

Any comparison of China and India stirs tremendous passion, interest, and debate among academics, policy makers, and social and political commentators around the world. In their article, which appears to be the first of its kind, Singh and Liu present a powerful analysis of how health, socioeconomic, and development patterns have changed in India and China during the past six decades[6]. According to the authors, although the two countries started out on a similar footing in the late 1940s, China appears to be doing better than India on several key health measures 60 years later. Because of more rapid improvements in health among the Chinese, the health gap between India and China, particularly in infant, child and maternal mortality and life expectancy, is wider now than ever before[6].

Child mortality rates continue to be the highest in the WHO African Region and South-East Asia Region[3]. Neonatal mortality, deaths during the first 28 days of life, accounts for 40% of all deaths among children under 5 years old globally, with Tanzania's rate of 34 per 1,000 live births being among the highest in Africa[3]. The article by Ajaari and colleagues examines the impact of place of delivery on neonatal mortality in rural Tanzania using a longitudinal population-based database, showing nearly twice the risk of neonatal mortality among births delivered outside health facilities compared with those delivered in health facilities attended by trained medical staff[7]. Despite a marked improvement in child survival over time, India's current under-five mortality rate of 66 per 1,000 live births remains higher than the global average[3]. In terms of the absolute burden, India accounts for nearly one-fourth of all under-5 deaths globally[3]. Given the significance of child mortality as a major public health problem in India, Mani and colleagues determine the effects of proximate or programmable determinants on under-five mortality in rural India by applying Cox-frailty and other hazard regression models to the data from the National Family Health Survey. Their analysis identifies maternal age, place of delivery, parity and birth spacing, infant's birth weight, and breastfeeding as significant determinants of under-five mortality[8].

Undernutrition among children is a major public health problem in many developing countries and the problem of underweight and stunting (low height-for-age) is particularly acute in Africa and Asia[3]. Using primary data collected for 405 school-aged children in Akwa Ibon State of Nigeria, Opara and colleagues examine the impact of intestinal parasitic infection on nutritional status of children[9]. According to their study, more than two-thirds of the Nigerian children in the sample were infected with at least one intestinal parasite, with the risk of stunting, wasting, and underweight being higher among children infected with intestinal parasites[9].

In their mixed-method paper, Macherera and colleagues make some stunning revelations[10]. Caregivers and guardians have become the newest but most intricate hindrance to access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) for children living HIV/ AIDS in rural Zimbabwe. Using data and information from focus groups conducted in a rural clinic and community, the authors demonstrate that while children growing up with HIV/AIDS continue to deal with stigma, discrimination, and rejection, they are embroiled with an unwinnable war within as their guardians are now using their ART medications to take care of themselves first. This paper highlights the urgent need to provide cross-generational access to ART especially in developing countries where targeting one group, like children, neglects the needs of other groups[10].

IJMA is founded on a pedestal of rigor and transparency. We conduct blind peer-reviews and select papers based on peer assessment of the merit of each contribution to advancing the field of MCH and HIV/AIDS both regionally and worldwide. With a robust editorial board reflecting the best and finest drawn from the six World Health Organization regions, our editorial board members are key to setting global health research agenda for our journal. Manuscripts by our editors pass through the highest level of our blind peer-review process conducted by experts in the field and from outside the board or the regions of the authors. We thank our friends and colleagues who have joined this coalition. From Oman to Nigeria, from India to Australia, we hope that the IJMA idea will outlive each and every one of us. We hope that IJMA will lay the foundation for highlighting and addressing global health challenges of developing countries by developing country scientists and policy makers. Happy reading!

References

- Social Determinants of Health: The Solid Facts. (2nd). Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe; 2003.

- [Google Scholar]

- Closing the Gap: Policy into Practice on Social Determinants of Health: Discussion Paper for the World Conference on Social Determinants of Health. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: World Health Organization; 2011.

- [Google Scholar]

- Towards the elimination of pediatric HIV: Enhancing maternal, sexual, and reproductive health services. International Journal of MCH and AIDS. 2012;1(1):6-16.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global health inequalities in cervical cancer incidence and mortality are linked to deprivation, low socioeconomic status, and human development. International Journal of MCH and AIDS. 2012;1(1):17-30.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Health improvements have been more rapid and widespread in China than in India: A comparative analysis of health and socioeconomic trends from 1960 to 2011. International Journal of MCH and AIDS. 2012;1(1):31-48.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of place of delivery on neonatal mortality in rural Tanzania. International Journal of MCH and AIDS. 2012;1(1):49-59.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Determinants of under-five mortality in Rural Empowered Action Group States in India: An application of Cox frailty model. International Journal of MCH and AIDS. 2012;1(1):60-72.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The impact of intestinal parasitic infections on the nutritional status of rural and urban school-aged children in Nigeria. International Journal of MCH and AIDS. 2012;1(1):73-82.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Social, cultural, and environmental challenges faced by children on antiretroviral therapy in Zimbabwe: A mixed-method study. International Journal of MCH and AIDS. 2012;1(1):83-91.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]