Translate this page into:

Global Health Donor Presence, Variations in HIV/AIDS Prevalence, and External Resources for Health in Developing Countries in Africa and Asia

✉Corresponding author email: reazuine@globalhealthprojects.org

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

Abstract

Objective:

The presence of multiple global health aid organizations in donor recipient countries at any point in time has led to arguments for and against aid coordination and aid pluralism. Little data, however, exist to empirically demonstrate the relationship between donor presence and longitudinal disease outcomes in donor-recipient countries. We examined the association between global health donor presence and changes in HIV/AIDS prevalence in 14 developing countries: 12 in Africa (Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Rwanda, South Africa, Uganda, Zambia, Burkina Faso and Mali) and compared them with two developing countries in Asia (India and Vietnam).

Methods:

To conduct our analyses, we conceptualized a framework for examining global health donor presence and disease outcomes. Donor presence data were derived from Mapping the Donor Landscape in Global Health: HIV/AIDS, a report published by the Kaiser Family Foundation, Washington, DC, USA. HIV/AIDS prevalence data were obtained and analyzed from the World Health Statistics and the Demographic and Health Surveys. Percent changes in national HIV/AIDS prevalence between 2009 and 2011 in the 14 developing countries were computed and correlation coefficients between donor presence and prevalence changes were calculated.

Results:

Between 2009 and 2011, HIV/AIDS prevalence decreased in all but one of the 14 developing countries with the presence of 21 or more global health donors. There was about 40% overall reduction in HIV/AIDS prevalence across the 14 countries in our analyses. South Africa recorded the most reduction in HIV/AIDS prevalence (-6.7%) followed by Zambia (-6.3, %), and Mozambique (-5.7%). Ethiopia was the only country without a reduction in HIV/AIDS prevalence (+0.1%). A correlation coefficient of 0.43 implied greater reductions in HIV/AIDS prevalence associated with increased donor presence.

Conclusions and Public Health Implications:

Our study shows a correlation between donor presence and HIV/AIDS disease burden in 14 donor-recipient countries. Our findings indicate that increased donor presence yields quantifiable reduction in global health disease burden. Further research is needed to demonstrate whether these gains can be observed in other global health disease outcomes.

Keywords

Global health

Donor presence

Donor coordination

Developing countries

Africa

Asia

HIV/AIDS

Global health conceptual framework

Introduction

At any point in time, there are numerous aid organi-zations providing development aid to address global health and other social and economic deve I opment issues in low and middle income countries (LMICs), also known as developing countries, a phenome-non referred to as “aid pluralism.” The pluralistic nature of aid organizations and the programmatic fragmentation that culminates from aid pluralism have led to increasing calls for donor coordination in aid assistance. According to proponents, donor coordination in global health and international devel-opment is important in maximizing population-level impact in global health.[1] There are ongoing worries about the fragmented nature of donor activities and presence manifested often in duplicative programs or programs that ought to complement each other. Advocates of donor coordination argue that aid co-ordination leads to efficiency and effectiveness; they further argue that efficiency and effectiveness ensure that increased funding subsequently culminates in the reduction in disease burden in nations receiving aid from a more coordinated donor community.[2]

In making their case for improved aid coordination, McCoy and colleagues[2] lamented that:

“The fragmented, complicated, messy and inad-equately tracked state of global health finance requires immediate attention. In particular it is necessary to track and monitor global health finance that is channeled by and through private sources, and to critically examine who benefits from the rise in global health spending.”

Implicit in the calls for donor coordination are two principal assumptions. First, proponents of do-nor coordination believe that the presence of multi-ple donor organizations both from the public (gov-ernments) and private (foundations) sector actors is a reality with inherent benefits. Second, calls for donor coordination are fuelled by the assumption of the potential benefits of pooled resources (or econ-omies of scale) in addressing major global health challenges within the donor receiving countries as evidenced in aid alignment through sector-wide ap-proaches.[3] More recently, proponents of donor co-ordination are energized by the emerging concept of “collective impact,” an organizing concept that opines the importance of leveraging broad sector co-ordination to achieve large-scale social change.[4] Col-lective impact opines that although large-scale social change requires broad cross-sector coordination, the social sector regrettably remains focused on the isolated intervention of individual organizations.[4] One apparent acknowledgment of the importance of donor coordination in global health was the founding, in 2002, of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuber-culosis, and Malaria (the Global Fund), an international financing institution working as a partnership between government, civil society, the private sector and communities living with TB, Malaria and AIDS.[5] Although it has enjoyed mixed reviews, Global Fund was a practical manifestation of the calls for donor coordination.

In opposition to aid coordination are proponents of aid pluralism who argue that having a range of active donors is in tandem with, and at the heart of, competitive economics that ought to be nurtured and not jettisoned within the development sector. [6,7] Proponents of aid pluralism argue that too much aid coordination is akin to low competition among donor organizations and that this could lead to un-intended negative consequences-creating new aid monopolies-a milieu that is fraught with little aid effectiveness.[8] According to this view point, donors enjoying monopoly in a sector are more likely to im-pose their biases on recipient countries, their staff, and potentially tie aid to conditions, demonstrate the political nature of and consequently alienate re-cipients detracting from the overall goals of these development aids.[9] Aid pluralism proponents iden-tify benefits of aid pluralism to include engendering of more ideas, competition, innovation, and consist-ent flow of funding.[6,7]

Calls for donor coordination and efforts or global health frameworks to engender donor coordination are not new, although they have been more promi-nent in the literature and in the advocacy world. In the last decade or so, there have been at least seven prominent global health efforts aimed at increasing donor coordination. These include the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development's (OECD's) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of I960; the United Nations Development Program of 1965; the Rome High Level Forum on Donor Harmonization of 2003; the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness of 2005; the Accra Agenda for Action of 2008; and the Busan Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation of 2011.[10] The 2005 Paris Declaration, endorsed by ministers of developed and developing countries and heads of multilateral and bilateral development institutions, committed to taking far-reaching and monitorable actions to reform the ways donor countries and agencies deliver and manage their aids. Five years later in 2010, leaders of eight leading global health agencies called for improved monitoring and evaluation of their own progress and performance and to be able to respond to increasing emphasis on results and accountability.[11] The Paris declaration earlier and the recent unified statement by the leading glob-al health leaders underscore one poignant fact: while aid volume and development assistance resources need to increase to achieve desired goals-which include addressing the outcomes for which the funds were disbursed-there is an urgency for results and/ or outcomes. Underscoring this is the increased calls for increase in aid effectiveness at the nucleus of which is coordination of aid assistance for collective impact.[11,12] It is not surprising therefore that the need to demonstrate the effectiveness of health de-velopment aid and assistance has culminated in calls for increased accountability in the reporting of glob-al health data.[2] Donor agencies are under increased scrutiny by their boards or governance arms to demonstrate the effectiveness of their programs as a necessary prerequisite to retaining donor loyalty. Donor countries are facing increased demands for accountability from national legislatures and citizens. Writhing under tough global economic down turn, many donor nations are under duress to discontinue providing global health development aid when their own citizens are experiencing widespread economic adversity. For example, United States slowed its de-velopment assistance for health, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria did not make any new grants for two years, and global health funding by UN agencies stagnated and even plummeted. [1] According to reports, at the peak of the global economic turmoil, between 2011 and 2012, devel-opment aid from the world's developed countries-who are the main aid donors-fell by 4%.[13]

A number of existing studies have evaluated the effects of global health initiatives on country health systems.[14,15] However, little data exist in the liter-ature to empirically demonstrate the relationship between donor presence and specific disease out-comes in donor-recipient countries. To address this gap in the literature, we examine the relationship between donor presence and change in HIV/AIDS prevalence in 14 low-and-middle-income countries (developing countries). This paper provides one of the first glimpses of who actually benefits from the rise in global health spending evidenced by the mag-nitude of donor presence.

Methods

We hypothesized an inverse relationship between donor presence and HIV/AIDS prevalence in devel-oping countries. Specifically, we expected that an increase in the number of donors in a particular country will result in a reduction in the prevalence of HIV/AIDS in the adult population between the periods for which data are available. Our goal was to empirically demonstrate the basic assumption of global health donor philosophy, i.e. using donor funding to reduce disease burden. To do so, we calculated the percent changes in national HIV/ AIDS prevalence between 2009 and 2011 in the 14 developing countries using the following mathematical formula: ((y2 -y1) / y1)*100. In addition, we examined the overall relationship by computing the correlation coefficients between donor presence and prevalence changes. We analyzed external sources of funding for national health expenditure in the 14 developing countries to explore whether, as we hypothesize, these resources increased in a pattern that mirrors the magnitude of donor presence in the developing countries analyzed.

Data on Donor Presence. We obtained data on donor presence from Mapping the Donor Landscape in Global Health: HIV/AIDS, a report published by the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), a non-profit organization that analyzes major health care issues facing the U.S., as well as the U.S. role in global health policy.[16] The report measures the landscape of donor presence based on analyses of data from the OECD Creditor Reporting System (CRS) database.

Briefly, the CRS database is the main source for comparable data across all major donors of inter-national assistance and represents development assistance disbursements as reported by the 22 member countries of the OECD's Development Assistance Committee, the European Commission and other international organizations.[10] Details of the CRS database are provided elsewhere.[10] The report calculates a cumulative number of global health donors and identified 14 out of 141 Developing countries with 20 or more bilateral or multilateral donors who provided development assistance for HIV for a three-year consecutive period covering the years 2009,2010, and 2011. Substantive and detailed description of the KFF's donor landscape reporting methodology can be found elsewhere.[16]

Data on HIV Prevalence. We extracted HIV/AIDS prevalence data among males and females aged 15-49 for the three-year period (2009-201 1) for the 14 developing countries with the highest presence of donors for HIV covered in the donor landscape report using 2009 as our baseline and 2011 as the comparison period. HIV/AIDS prevalence data for the years 2009 and 2011 were obtained from the World Health Statistics 2011[17] and the World Health Statistics 2013[18] respectively. We augmented the prevalence data for two countries-Ethiopia and India-with data from the 2005 and 2011[19,20] Ethiopia Demographic and Health Surveys, and the 2005 India Demographic Health Surveys respectively.[21] The World Health Statistics and the Demographic Health Surveys are major sources of global epidemiological and demographic data with well-described metho-dologies. Percentage, positive or negative changes, in national HIV/AIDS prevalence between 2009 and 2011 in the 14 countries were computed and corr-elation coefficients between donor presence and changes in prevalence were calculated using Microsoft Excel.[22]

Data on External Resources for Health. We obtai-ned data on the external resources for health from the World Health Organization's National Health Account database published by the World Bank. The external resources for health captures the totality of funds or in-kind services that a nation receives from external entities.[22] We computed the comparison data for the two most recent years of available data within the periods 2009 and 2011.

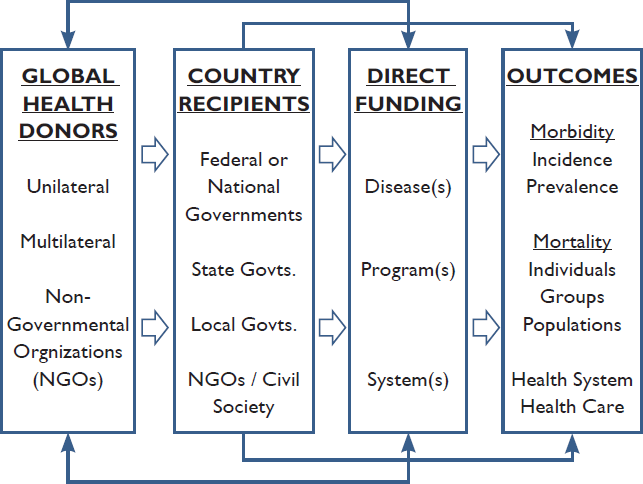

Global Health Conceptual Framework: Existing global health conceptual frameworks have not ex-amined the relationship between donor presence and change in health outcomes.[23,24,25] To address this gap and to guide our analyses, we conceptual-ized a global health donor-presence and disease outcome conceptual framework (Figure 1) for un-derstanding the proximal and distal relationships between donor presence and disease outcomes in developing countries. In our conceptual framework, we theorize that, at any given time, there is a collection of different global health donor organizations in a given developing country. These include unilateral, multilateral, and non-governmental donor organi-zations. We acknowledge in our framework that the intensity of donor presence in any developing country at any given time is dictated by the politi-co-economic situation at the donor agency's home country but more so at the donor-recipient nation lending credence to some countries being described as “donor havens.”[26] and Disease Outcome Conceptual Framework

- Global Health Donor Presence

According to our conceptual framework, direct donor funding are disbursed at the recipient level via the highest national levels through government agencies namely, national governments, state govern-ments, local governments, and national-level non-gov-ernmental or civil society organizations. Using these funds, national governments and/or non-government actors can address disease outcomes. Although do-nors disburse funds directly to national governments, the impact on disease outcomes is indirect. Some experts argue that disbursing funds through national governments provides the best potential for large-scale roll-out and national/population level impact therefore affecting outcome.[27,28]

Our global health framework shows that some global health donors disburse funds in developing countries through direct disbursement to specific diseases, programs, or system improvement pro-jects at the national level. Through this mechanism, donors directly fund their priorities without going through government agencies. These types of direct disbursements have shorter latency and impact on disease outcomes because the recipients can affect outcomes more directly than they would if they had gone through government agencies. However, this type of indirect global health donor disbursements that do not go through government agencies have been frowned upon as a veiled method for averting national bureaucracy.[27] This type of funding mech-anism is very fluid and are less utilized. Finally, our framework posits that, regardless of the donor dis-bursement pathway, the association between donor intensity can be empirically tested by evaluating the degree to which donor presence affects morbidity (incidence and prevalence) or reduces mortality (at individual, group, or population-level) in any given LMIC.

Results

HIV/AIDS Prevalence. All but two of the 14 deve-loping countries with the highest donor presence were from sub-Saharan Africa. The two exceptions were Vietnam and India from South East Asia. Alto-gether, 332 donors provided development assistance for HIV/AIDS in the 14 countries included in this analysis. Ethiopia has the highest number of donor presence of 27, followed by Kenya with 26 donors. Each of Tanzania, Malawi, Zimbabwe and Mozambique had 25 donors. Our analyses showed that within the two-year period, HIV/AIDS preva-lence decreased in all but one of the 14 developing countries with the presence of 20 or more global health donors (see Table 1). In 2009, there was a combined HIV/AIDS prevalence (unweighted aver-age) burden of 6.7% in the 14 countries. In 2011, this burden dropped to 4.0%. Overall, there was about 40% reduction in HIV/AIDS prevalence across the 14 developing countries in our analysis. South Africa recorded the most reduction in HIV/AIDS prevalence (-6.7%) followed by Zambia (-6.3%), and Mozambique (-5.7%). The HIV/AIDS prevalence in Malawi dropped from 11% in 2009 to 6% in 2011, a 5.1% reduction in HIV prevalence. With the highest number of donor presence among the 14 countries, Ethiopia was the only country that did not achieve a reduction in HIV/AIDS prevalence (+0.1%) be-tween the two periods. The correlation coefficient between donor presence and changes in HIV/AIDS prevalence for 12 countries (excluding Ethiopia and India) was estimated to be 0.43, implying that the higher the number of donors present, the greater the reduction in HIV/AIDS prevalence.

| Country | No. of Donors Present, 2013 | HIV/AIDS Prevalence, 2009a,b | HIV/AIDS Prevalence, 2011a,b | Change in HIV/AIDS Prevalence, 2009-2011 | Absolute Decrease in HIV/ AIDS Prevalence, 2009-2011 | % Decrease in HIV/ AIDS Prevalence, 2009-2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethiopia | 27 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 0.1 | -0.1 | -7.1 |

| Kenya | 26 | 6.3 | 3.9 | -2.4 | 2.4 | 38.1 |

| Tanzania | 25 | 5.6 | 3.4 | -2.2 | 2.2 | 39.3 |

| Malawi | 25 | 11.0 | 5.9 | -5.1 | 5.1 | 46.4 |

| Zimbabwe | 25 | 14.3 | 9.7 | -4.6 | 4.6 | 32.2 |

| Mozambique | 25 | 11.5 | 5.8 | -5.7 | 5.7 | 49.6 |

| Rwanda | 23 | 2.9 | 1.9 | -1.0 | 1.0 | 34.5 |

| South Africa | 23 | 17.8 | 11.1 | -6.7 | 6.7 | 37.6 |

| Uganda | 23 | 6.5 | 4.0 | -2.5 | 2.5 | 38.5 |

| Vietnam | 23 | 0.4 | 0.3 | -0.1 | 0.1 | 25.0 |

| Zambia | 23 | 13.5 | 7.2 | -6.3 | 6.3 | 46.7 |

| India | 22 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Burkina Faso | 21 | 1.2 | 0.7 | -0.5 | 0.5 | 41.7 |

| Mali | 21 | 1.0 | 0.7 | -0.3 | 0.3 | 30.0 |

a HIV/AIDS Prevalence per 100,000 Population.

b HIV/AIDS Prevalence are Reported for Adults 15-49 Years.

External Sources of Funding. External resources for health account for part of a nation's health expenditure and for developing countries, these are from multiple mechanisms including foreign governments, bilateral organizations, or foreign nonprofit organizations.[22] Conceptually, external resources for health should mirror the magnitude of donor presence in developing countries and should increase with increasing donor presence. We found that between 2009 and 2010, external resources for health accounted for greater than 20% of the total health expenditures in 10 of the 14 developing countries in this analysis (see Table 2). In Mozambique, Malawi, Rwanda, and Zambia, external resources for health accounted for 62%, 58%, 48% and 44% of the total national expenditure on health. External resources for health increased in all but five of the 14 countries between 2009 and 2010 demonstrating that donor contributions provide substantial cushion to donor-recipient countries.

- Percent Decrease in HIV/AIDS Prevalence from 2009-2011 in Developing Countries

- Percent Decrease in External Resources for Health from 2009-2010 in Developing Countries

| Country | No. of Donors Present, 2013 | External Resources for Health, 2009 | External Resources for Health, 2010a | Change in External Resources for Health, 2009-2010 | % Change in External Resources for Health | Type of Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethiopia | 27 | 38.0 | 36.1 | -1.9 | -5.0 | Decrease |

| Kenya | 26 | 34.0 | 37.9 | 3.9 | 11.5 | Increase |

| Tanzania | 25 | 53.4 | 39.6 | -13.8 | -25.8 | Decrease |

| Malawi | 25 | 80.0 | 58.1 | -21.9 | -27.4 | Decrease |

| Zimbabwe | 25 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Mozambique | 25 | 33.6 | 62.2 | 28.6 | 85.1 | Increase |

| Rwanda | 23 | 49.0 | 48.0 | -1.0 | -2.0 | Decrease |

| South Africa | 23 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 0.4 | 22.2 | Increase |

| Uganda | 23 | 20.4 | 27.6 | 7.2 | 35.3 | Increase |

| Vietnam | 23 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 0.2 | 6.7 | Increase |

| Zambia | 23 | 38.5 | 43.7 | 5.2 | 13.5 | Increase |

| India | 22 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 18.2 | Increase |

| Burkina Faso | 21 | 26.0 | 36.1 | 10.1 | 38.8 | Increase |

| Mali | 21 | 26.3 | 22.2 | -4.1 | -15.6 | Decrease |

a Data are provided for the latest year for which data are available.

Discussion

Calls for more donor coordination have gained increasing traction due to the global economic downturn of the last few years.[13] More funding organizations and countries are demanding for empirical evidence that their aids donations change lives and making the desired impact in the lives of average people in the developing world. Almost four years ago, before the global economic downturn, McCoy and colleagues lamented that the fragmented, complicated, messy and inadequate tracking of the state of global health finance require immediate attention.[2] They opined that it was particularly necessary to track and monitor global health finance that is channeled by and through private sources, and to critically examine who benefitted from the rise in global health spending. Our study begins to address this need and provides one of the few empirical data on the impact of global health aids in developing world. We must emphasize that the data we present in this analysis represent associations, albeit correlations. We are cognizant of the many nationally driven programs and expenditure for HIV/ AIDS that are taking place in these countries and do not intend to minimize these efforts. Further studies might be needed to explore the national expenditure/ spending on overall health and HIV/AIDS specifically in each of these countries and find to what extent can the benefits of the fight against HIV/AIDS could have been substantially driven by international aid. More studies are needed to empirically support the relationships presented in our debutant conceptual frame work presented given the paucity of con-ceptual frameworks exploring donor presence and global health disease burden.[29,30]

Conclusion and Global Health Implications

HIV/AIDS prevalence remains unacceptably high in developing countries. However, results from this study show that the global health investments are yielding fruit in addressing the epidemic in these poor countries of the world. Given the increasing scrutiny and often criticisms facing global health donor organizations, findings from this study could provide some evidence to demonstrate that pop-ulations in developing countries obtain improved health outcomes from donor organizations. Making the connection between aid and improved health outcome is at the center of global health and in-ternational development. Many donor organizations conduct impact evaluations of their programs to make this point. However, results of these evalu-ations are not widely disseminated firstly because some of the results were not what the sponsors intended or secondly because these reports did not garner enough support by both sponsors and evaluators that dissemination becomes challenging. Our study provides important information for glob-al health officials in the countries included in this country to examine benefits from donor organizations. For managers of global health organizations, our study provides solace that aids work especially in countries where they are directed at need and to the affected populations.

Financial Disclosure:

None to report.

Ethical approval:

No IRB approval was required for this study, which is based on the secondary analysis of publicly available databases.

Acknowledgements:

The views expressed are those of the authors' and not necessarily those of their respective organizations.

Conflicts of Interest:

None.

Funding/Support:

None.

References

- The Global Financial Crisis Has Led To A Slowdown In Growth Of Funding To Improve Health In Many Developing Countries. Health Affairs. 2011;31(1):228-235.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global health funding: how much, where it comes from and where it goes. Health Policy and Planning. Health Policy and Planning. 2009;24(6):407-417.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aid Alignment: A Longer Term Lens on Trends in Development Assistance for Health in Uganda. Global Health. 2013;9(7)

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Global Fund for The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. The Global Fund for The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. [Online] 2002. [cited 2014 January 25. Available from: http://www.theglobalfund.org/en/about/

- [Google Scholar]

- Crushed Aid: Fragmentation in Sectoral Aid. Working Paper No. 284. OECD, OECD Development Centre 2010

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness and the Accra Agenda for Action. [Online].; 2008 [cited 2013 July 21. Available from: www.oecd.org/development/effectiveness/34428351.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Keeping a tight grip on the reins: donor control over aid coordination and management in Bangladesh. Health Policy and Planning. 1999;14(3)

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foreign Aid: International Donor Coordination of Development Assistance. In: CRS Report No. R4l 185. Washington, DC: USA : Congressional Research Service; 2013.

- [Google Scholar]

- Meeting the Demand for Results and Accountability: A Call for Action on Health Data from Eight Global Health Agencies. PLoS Medicine. 2010;7(1)

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness and the Accra Agenda for Action. Washington, DC: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD); 2005.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aid to Poor Countries Slips Further as Governments Tighten Budg-ets. [Online].; 2013 [cited 2013 July 21. Avail-able from: http://www.oecd.org/newsroom/ aidtopoorcountriesslipsfurtherasgovernmen tstightenbudgets.htm

- [Google Scholar]

- The Effects of Global Health Initiatives on Country Health Systems: a Review of the Evidence from HIV/AIDS Control. Health Policy and Planning. 2009;24(4):239-252.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National and subnational HIV/AIDS coor-dination are global health initiatives closing the gap between intent and practice. Globalization and Health. 2010;16(3)

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mapping the Donor Landscape in Global Health: HIV/AIDS. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2013.

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Statistics 2013. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2013.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ethiopia Demographic and Health Surveys. [Online].; 2005 [cited 2013 July 21. Available from: http://www.measuredhs.com

- [Google Scholar]

- Ethiopia Demographic and Health Surveys. [Online].; 2011 [cited 2013 July 21. Available from: http://www.measuredhs.com

- [Google Scholar]

- India Demographic and Health Surveys. [Online].; 2005 [cited 2013 July 21. Available from: http://www.measuredhs.com

- [Google Scholar]

- Open Data - Indicators. [Online].; 2014 [cited 2014 January 25. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/ indicator/SH.XPD.EXTR.ZS

- [Google Scholar]

- Globalization and Health: a Framework for Analysis and Action. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 2001;79(9):875-881.

- [Google Scholar]

- The “Global Health” Education framework: a Conceptual Model for Monitoring, Evaluation and Practice. Globalization and Health. 2011;7(8)

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparative Health Systems: a Conceptual Framework. Journal of Health amd Human Services Administration. 1998;20(4):520-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Does Political Stability Improve the Aid-growth Relationship? Apnel Evidence on Selected Sub-saharan African Countries. African Review of Economics and Finance. 2010;2(1)

- [Google Scholar]

- Bypass or Engage? Explaining Donor Delivery Tactics. Princeton, Rhode Island: Princeton University, Niehaus Center for Globalization and Governance; 2011.

- [Google Scholar]

- Foreign Aid Delivery, Donor Selectivity and Poverty: a Political Economy of Aid Effectiveness. Rhode Island: Princeotn University, Niehaus Center for Globalization and Governance; 2011.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Health Impacts of Globalization: a Conceptual Framework. Global Health. . 2005;3(1):14.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Need for a Trans-Disciplinary, Global Health Framework. Journal of Alternative Comple-mentary Medicine (2):179-84.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]