Translate this page into:

Assessing Reproductive Decision-making Among HIV-Positive Women in Kumasi, Ghana

*Corresponding author email: rreece@hsc.wvu.edu

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background or Objectives:

HIV-positive women have higher rates of unmet need for contraception and unintended pregnancy and face unique obstacles in accessing family planning services, such as healthcare-related stigma and disclosing HIV status to partners. This study characterizes factors that influence the reproductive decision-making of women living with HIV and identifies areas for improvement in reproductive counseling in Kumasi.

Methods:

In this cross-sectional study, HIV-positive women, ages 18 to 45 years, presenting for care at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital between June and August 2017 were interviewed using structured surveys. Information gathered included demographics, method of contraceptive use, initiation of anti-retroviral therapy (ART), knowledge and use of contraception, and future reproductive plans. The primary outcome was current family planning use and future reproductive desire. Univariate analysis was used to characterize the demographics of the study group. Bivariate analysis including Chi-squared test was employed to assess the association between use of family planning between women with an HIV-positive and HIV-negative partner, with significance set at p < 0.05.

Results:

A total of 88 women were interviewed. The unmet need for contraception was 10%. Among all sexually active women, 26% did not use contraception. Fewer women with HIV-negative or untested partners were using contraception (65% and 67%, respectively), compared to women with HIV-positive partners (93%). Partner preference was the most common reason cited for not using a method of contraceptive (46%). Similar trends were found in future reproductive desires based on age cohorts, partner status, and use of family planning.

Conclusion and Global Health Implications:

Significant barriers to family planning use among HIV-positive women remain, especially those with a serodiscordant partner. Most partners were aware of their partner’s HIV status. This highlights an important opportunity to include partners in HIV and contraceptive counseling.

Keywords

HIV

Family planning

Contraception

LARC

Serodiscordant

Ghana

Africa

1. Introduction

1.1. Background of the study

It is estimated that there are 36.7 million individuals living with HIV worldwide, and that nearly 70% of those individuals live in Sub-Saharan Africa; women account for almost 60% of the total population living with HIV in western and central Africa.1 Use of contraception to prevent unintended pregnancy is among the World Health Organization’s (WHO) recommendations for prevention of maternal-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV.2 Furthermore, contraception use and family planning services are an important part of supporting women in achieving a desired family size. Future reproductive concerns and intention to have children among HIV-positive women lie within the perceived effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy (ART), as well as adequate knowledge regarding transmission and prevention. The desire to reproduce among HIV-positive women is associated with the perceived efficacy of PMTCT and ART in having an HIV-free baby,3 and sense of maternal health and well-being.4,5

Prior studies investigating future fertility desire among HIV-positive women in Ghana have reflected similarities to other regions of sub-Saharan Africa: younger age, having fewer children, and partner fertility desire have been shown to be associated with women’s fertility desires.6 However, studies have shown that HIV-positive women living in sub-Saharan countries have a higher unmet need for family planning,6 and are more likely to have unintended pregnancies, both unwanted and untimed, compared to HIV-negative women.7,8 HIV-positive women in Kumasi specifically have previously had an estimated unmet need for contraception of nearly 28%, which is comparable to rates in other regions of sub-Saharan Africa.9 While previous research has investigated factors impacting contraceptive use and future childbearing for women in other patient populations of Ghana,10 there is currently no information on the factors influencing family planning use for women seeking care at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital (KATH) in Kumasi, Ghana.

1.2. Objectives of the study

Women living with HIV face unique obstacles in accessing and utilizing adequate family planning and reproductive services. These include, but are not limited to, barriers in condom use related to reluctance to disclose status, desires to have children in the setting of unmet treatment and counseling needs, barriers to adequate family planning counseling such as spousal or partner approval, cultural beliefs, and stigma.11 Family planning has been shown to be a significant predictor of optimal retention to antiretroviral and postpartum care in HIV-positive women in Kumasi.12 In order to make contributions to specific recommendations aimed at improving fertility and family planning counseling for HIV-positive women in Kumasi, this study seeks to characterize the environment in which HIV-positive women presenting for care at KATH make reproductive decisions, the level at which those decisions are met with adequate services, and areas of improvement in reproductive counseling. This information will guide counseling during prenatal time when women are seeking care, hopefully improving retention to postpartum care, as well as identify gaps in education to be addressed.

Specifically, the aims of this study were to (1) update the unmet need for family planning and identify current barriers to family planning use, and (2) describe factors affecting future reproductive desires among HIV-positive women being cared for at KATH.

2. Methods

This was a cross sectional study conducted at KATH in Kumasi, Ghana, the second largest teaching hospital in Ghana and the single tertiary care center in the Ashanti region. KATH serves as the referral center for 7 out of the 10 regions in Ghana with a catchment area of 9 million people. The adult HIV clinic at KATH is also one of the main outpatient sites for HIV/AIDS care in Ghana. It alone now serves over 10,000 patients.

A convenience sample of women presenting for care at the HIV clinic at KATH between June and August 2017 were screened for eligibility. Women were eligible if they were between 18 and 45 years of age, HIV-positive, and spoke English or Twi, the local language. Eligible women were approached before or after their clinic visit and consented. Enrolled women then met with research personnel and a Twi translator, if needed, to complete the study survey.

2.1. Study variables

The primary outcome was current family planning use and future reproductive desire. Independent variables included partner status, future reproductive plans, and age. Structured self-reported surveys were administered by research personnel to a convenience sample of patients in the clinic to assess demographics, pregnancy history, partner information, diagnosis history and ART use, current method of contraception, frequency of condom use, and plans for future pregnancy. Through a check-all-that-apply question, women who were sexually active were asked to indicate their reasons for not currently using contraception, if applicable. Answer choices included, “I worry about the side effects/how it would affect my health,” “My partner does not want to use a method of birth control,” “It is difficult for me to afford methods of birth control,” “It is difficult for me to access/obtain methods of birth control,” “I do not know about methods of birth control,” and “I want to have a child.” Women were also asked if they desired to have (more) children in the future. If they did not, they were then asked through a check-all-that-apply question the reasons. Answer choices included “HIV or health reasons,” “I cannot afford more children,” “I fear my child will be infected,” “I have had tubal ligation,” “I don’t want any (more) children/desired family size achieved,” and “I am afraid of infecting my partner”. The percentage of unmet need for family planning was calculated based on the United Nations (UN) definition,13 which is the quotient of sexually active women of reproductive age who have an unmet need and total number of sexually active women of reproductive age in a population. According to the UN, unmet need is defined as women of reproductive age (15-49 years) who are sexually active and report not wanting any children or wanting to delay childbearing for at least 2 years, but not using a form of contraception.

2.2. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was undertaken using SPSS Version 22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). Univariate analysis was used to characterize the demographics of the study group. Bivariate analysis including Chi-squared test was employed to assess the association between (1) women’s partner status and use of family planning, and (2) women’s partner status, family planning use, or age and future plans to get pregnant within the next 2 years, in 2 or more years, or not at all. Significance was set at p < 0.05.

2.3. Ethical approval

This study was approved by the institutional review board at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, USA, and the Committee on Human Research, Publications, and Ethics at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, School of Medical Sciences and KATH, Kumasi, Ghana.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic information

In all, 640 women were eligible during the study period of June to August 2017, and 90 women were able to be approached for enrollment before or after their clinic visits. A convenience sample of 88 women (98%) were consented and interviewed. Table 1 presents the demographic information for the study cohort. Most women (47%) were between 40 and 45 years old, with the mean age (SD) being 38.1 (5.6). A majority of women (73%) had a basic level of education. The average age (SD) at HIV diagnosis was 30.8 (5.8), and the mean time (SD) from diagnosis to initiation of ART therapy was 1.3 (2.5) years. In total, 97% of women were on ART, and 54% were started on ART therapy at the time of diagnosis. The marital status of women in this study cohort was mixed, with the greatest percentage of women being married (36%).

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age group | |

| 20-29 | 8 (9) |

| 30-39 | 39 (44) |

| 40-45 | 41 (47) |

| Level of education | |

| None | 8 (9) |

| Basic | 64 (73) |

| Secondary | 10 (11) |

| Tertiary | 6 (7) |

| Relationship Status | |

| Single | 18 (20) |

| Married | 32 (36) |

| Divorced | 12 (14) |

| Cohabitating | 11 (13) |

| Widowed | 15 (17) |

| Sexually active | 50 (57) |

| ART therapy | 85 (97) |

| Age of HIV diagnosis, years (SD) | 30.8 (5.8) |

| Time from diagnosis to ART, years (SD) | 1.3 (2.5) |

3.2. Unmet need for family planning and barriers to its use

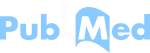

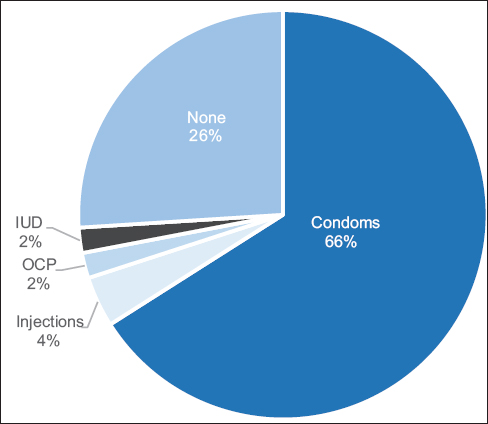

Of the 88 women interviewed, 50 were sexually active at the time of the study (Table 2). In total, 37 sexually active women (74%) were using a form of family planning. The most common method of family planning was condoms used by 33 women (66%) (Figure 1). Thirteen sexually active women (26%) were not using a form of family planning. The calculated unmet need for family planning in this study cohort was 10% (Figure 2). Among these 13 women, the most common reason for not using a form of family planning was, “my partner does not want to use a method of birth control” (n=6), followed by “I want to have a child” (n=5) (Figure 3). Two women provided other unlisted options for not using family planning, one of which was unknown and the other being a “lack of support” related to her desires to delay childbearing in opposition to her partner’s and family’s desires. One woman with an HIV-positive partner reported being “not currently sexually active” as reason for not using contraception, which may reflect a misinterpretation of the initial demographic question. The following were not cited as reasons for not using a form of family planning: “It is difficult for me to afford methods of birth control,” “It is difficult for me to access/obtain methods of birth control,” and ”I do not know about methods of birth control.”

| Using family planning, N (%) | 37 (74) |

| Partner status, N (%) | |

| HIV-positive | 15 (30) |

| HIV-negative | 20 (40) |

| Untested/unknown | 15 (30) |

- Method of family planning among sexually active women (N=50).

- Unmet need for contraception

- Source: The estimated unmet need for contraception is calculated as the number of sexually active women of reproductive age who wish to cease childbearing or delay childbearing > 2 years but are not using a method of contraception, divided by the total number of sexually active women of reproductive age.13

- Reasons cited for not using family planning among sexually active women (N=13)

- Source: One woman with an HIV-positive partner cited “not currently sexually active” as reason, and is therefore not included in this figure. Women were able to choose multiple answers. Other answer options not chosen by women: “It is difficult for me to afford methods of birth control”; “It is difficult for me to access/obtain methods of birth control”; and ”I do not know about methods of birth control.”

Among the sub-cohort of 50 sexually active women, 15 (30%) had an HIV-positive partner, 20 (40%) had an HIV-negative partner, and 15 (30%) had a partner who was untested for HIV. In order to achieve adequate group size for statistical analysis, family planning use among women with HIV-positive and untested partners were grouped and compared to women with HIV-negative partners. Though group difference was not found to be significant (80% vs. 65%, p=0.23), looking at each group separately, 14 women (93%) with HIV-positive partners were using a form of family planning compared with 13 women (65%) with HIV-negative partners and 10 women (67%) with untested partners. All women with HIV-positive and -negative partners reported that their partners were aware of the participant’s HIV status. However, only 6 women (40%) with untested partners reported their partners were aware.

3.3. Factors impacting current and future reproductive decision-making

Regardless of marital status or current sexual activity, all women were assessed for their future desires to have children. Among all 88 women in the study, 33 (37.5%) did not desire (more) children in the future. The most common reason for ceasing childbearing was due to HIV or other health reasons (60.6%), followed by having achieved a desired family size (27.2%) (Table 3). However, 8 women (24%) reported a fear of vertical transmission. Most women who were sexually active desired (more) children in the future (62%), as did most of their partners (60%). Fifty-six percent of sexually active women desired (more) children within the next 2 years. In order to achieve adequate group size for statistical analysis, women with HIV-positive and untested partners were grouped and compared to women with HIV-negative partners. There was no significant difference in proportion of women that desired children within 2 years based on partner status (63% vs. 45%, p=0.20). There was also no signficant difference in family planning use between women who desired children within 2 years compared with women who wanted to delay for 2 or more years or cease childbearing (71.4% vs. 77.2%, p=0.64). There was also no signficant difference in future reproductive desires (proportion of women wanting children within 2 years, in 3+ years, or cease childbearing) between age cohorts (age 20-29, 30-39, 40-45 years).

| Reason | N (%) |

|---|---|

| “HIV or other health reasons” | 20 (61) |

| “Achieved a desired family size” | 9 (27) |

| “I fear my child will be infected” | 8 (24) |

| “I am afraid of infecting my partner” | 2 (6) |

| “Other” | 2 (6) |

| “I cannot afford more children” | 1 (3) |

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion

The aim of this study was to characterize the factors associated with reproductive decisions among HIV-positive women receving care at major referral hospital in Kumasi, Ghana, the level at which those decisions are met with adequate services, and areas of improvement in reproductive counseling. Previous studies have elucidated the unique barriers to reproductive healthcare faced by women living with HIV in high-prevalence areas.11,14-16 However, region-specific characteristics allow for targeted improvement in current resources. In this cross-sectional study of HIV-positive women in Kumasi, we found that while most women with HIV-positive partners were using contraception, a much lower percentage of women with HIV-negative and untested partners were doing the same. The most common reason cited for not using contraception was partner preference. A smaller percentage of untested partners were reportedly aware of the participant’s HIV status compared to HIV-positive and -negative partners. The most common reason cited for ceasing childbearing was due to HIV or other health concerns.

Sero-cordant couples had a much higher rate of family planning (93%) compared with sero-discordant couples (65%). The reasons for not using family planning appear to be associated with partner preference and reproductive desire, but did not hinder on access or knowledge of contraception for women in this study. A previous study of 230 HIV-positive women in Kumasi, Ghana found that contraception use was associated with partner knowledge of HIV status.9 The current study highlights a more nuanced point that, while all partners were reportedly aware of the participant’s HIV status, discrepancies in family planning use persisted. The stark difference between HIV-positive and -negative or untested partners engaging in family planning suggests that this difference is due to dual HIV and family planning counseling provided to women visiting the clinic, but not necessarly to partners that are not HIV-positive. Prior studies have shown that enrollment in HIV care has been shown to increase the rates of condom and hormonal contraception use among serodiscordant couples.17 Incorporation of HIV-negative partners in counseling would diminish additional barriers to women implementing the counseling she receives into her relationship based on partner dynamics and communication.

The pattern of partner preference in contraceptive decision-making highlighted in this study lends itself to a discussion about involving men in HIV counseling and testing. A 2015 study by Kumar et al. of adults presenting to the KATH HIV clinic found that men were more likely to be older, with lower CD4+ count and clinical symptoms at the time of HIV diagnosis compared to women.18 The current study found that the lowest proportion of partners that were aware of the participant’s HIV status were partners who were untested, and all partners who were HIV-negative were aware. This supports the two-fold impact of improving outreach and incorporation of men in HIV care, which is improving testing and early detection and providing an opportunity for discussion between serodiscordant couples with clinicians regarding status, safety, and family planning.

Our findings also suggest that condoms, as the most common method of contraception reported by women in this study, may be employed with greater intention to prevent HIV transmission than to prevent pregnancy. The use of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) among women in this study was low (6%). We found a similar proportion of women who desired and did not desire future pregnancies were using family planning. That is to say, even a majority women who wanted to get pregnant were using family planning. This is similar to a previous study in Accra that found most women wanted to have children but were also using family planning; most women in this study preferred to discuss family planning with their HIV clinician.19 The high ART uptake and reported accessibility to family planning further supports an oppportunity to combine and enhance family planning counseling and education with HIV care. In addition, there remained a noninsignificant percentage of women who reported ceasing childbearing due to a fear of vertical transmission of HIV (24%). This is in spite of the high percentage who were on ART with a relatively short delay, on average, between diagnosis and initiation of therapy. This highlights an important area for improvement in counseling that centers on safe and adequate pregnancy planning alongside HIV care.

It is important to note that nearly all women in this study were on ART, with a relatively short delay between diagnosis and initiation of therapy (1.3 + 2.5 years). The unmet need for contraception in this cohort (10%) is lower than previously reported for Kumasi.9 Women also did not cite problems with access to contraception as reasons for not using family planning at the time of the study. Such a success in access to both HIV and reproductive care has been supported by international efforts and funds to expand and disseminate providers and medications to low-resource areas. This success is threatened by policies that could defund clinics providing HIV care alongside family planning services, which includes but is not limited to abortion-related care. Under the United States (U.S.) Mexico City policy, also referred to as the “global gag rule”, NGOs are prohibited from receiving funds through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) if they provide any abortion-related care outside cases of an rape, incest, or a threat to the life of the woman, provide counseling for abortions, or advocate to legalize or improve access to abortions in their country.20 Most recently, the global gag rule has been not only reinstated but expanded in 2017 to now include all global health organizations receiving USAID funding, compared with only family planning organizations in the past. While the success of HIV care and access to contraception in Ghana has been steadily improving,21-23 it is currently unclear how policy changes will impact this success.

4.2. Limitations

To our knowledge, this study is the first to characterize the factors associated with contraceptive use as well as future reproductive plans among women living with HIV in Kumasi, Ghana. However, this study has a few limitations. A small sample size limits the statistical power of the study. The cross-sectional study design cannot identify causality, and there is an inherent limitation of self-reporting and social desirability bias in this design for patient and partner information. Partners were not interviewed as part of this study, and therefore partner information and opinions were obtained through the female participants. Generalizability is limited, as data was collected on HIV-positive women presenting for HIV care and counseling, and therefore does not include women lost-to-follow up or unable to utilize the clinic for care. These women may represent a subgroup with the highest rates of unmet need for contraception and inadequate education based on the nature of dual counseling that occurs at the HIV clinic.

4.3. Recommendation for further studies

This study highlights the importance of partner preference and communication in both HIV and reproductive care. Further investigation is needed to characterize specific barriers to open communication regarding family planning among couples. A feasibility study for an educational intervention involving male partners, regardless of HIV status, will likely shed light on how to best include partners in HIV and reproductive counseling while determining acceptance of use. Development and implementation of an educational intervention for women and partners should focus on methods of family planning including long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), as there was low uptake among women in this study; partner outreach and education; importance of ART adherence for PMTCT, as this was a cited fear of nearly a quarter of women in this study.

5. Conclusion and Global Health Implications

This study characterizes the factors affecting reproductive decision-making among HIV-positive women in a major referral center in Kumasi. There are significant barriers to the use of contraception among HIV-positive women, especially among women with an HIV-negative or untested partner. Partner preference appears to be the primary obstacle to contraceptive use. Other hypothesized barriers including cost, accessibility, knowledge, and side effects were not cited by women in this study. Factors that did not appear to influence future reproductive desires included age, partner status, and current use of family planning. Most partners were aware of their partner’s HIV status, which highlights an important opportunity to include partners in HIV and contraceptive counseling. Future studies should consider developing and implementing educational interventions for HIV-positive women and their partners. Such interventions could focus on: (1) modern methods of contraception, (2) partner outreach, testing, and education, and (3) importance of ART adherence for prevention of maternal-to-child transmission.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the supportive staff of KATH HIV clinic, including Shadrack Osei Asibey.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

Funding/Support: This research was supported by the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University Summer Assistantship.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, USA and the Committee on Human Research, Publications, and Ethics at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, School of Medical Sciences and Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital in Kumasi, Ghana.

References

- Fact Sheet November 2016. http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet

- 2012. Preventing HIV and Unintended Pregnancies:Strategic Framework 2011–2015. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/linkages/HIV_and_unintended_pregnancies_SF_2011_2015.pdf

- Fertility desire and associated factors among people living with HIV attending antiretroviral therapy clinic in Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:382.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fertility intentions among HIV positive women aged 18–49 years in Addis Ababa Ethiopia:a cross sectional study. Reproductive Health. 2014;11(1)

- [Google Scholar]

- Reproductive experience of HIV-infected women living in Europe. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(9):2140-2144.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fertility Preferences of Women Living with HIV in the Kumasi Metropolis, Ghana. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2015;19(2):125-133.

- [Google Scholar]

- Unmet need for effective family planning in HIV-infected individuals:results from a survey in rural Uganda. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2012;38(1):23-29.

- [Google Scholar]

- Unmet need for family planning, contraceptive failure, and unintended pregnancy among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women in Zimbabwe. PLoS One. ;9(8):e105320.

- [Google Scholar]

- Contraceptive use and unmet need for family planning among HIV positive women on antiretroviral therapy in Kumasi, Ghana. BMC Women's Health. 2014;14:126.

- [Google Scholar]

- Contraceptive Characteristics of Women Living with HIV in the Kumasi Metropolis, Ghana. International Journal of MCH and AIDS. 2013;2(1):111-120.

- [Google Scholar]

- Meeting the Sexual and Reproductive Health Needs of People Living with HIV. Guttmacher Policy Review. 2006;9(4):17-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Retention in Care of HIV-Positive Postpartum Females in Kumasi, Ghana. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2016;15(5):406-411.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2014. World Contraceptive Use. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/dataset/contraception/wcu2014.asp

- Barriers to communication between HIV care providers (HCPs) and women living with HIV about child bearing:A qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(5):754-759.

- [Google Scholar]

- Barriers to Access of Maternity Care in Kenya:A Social Perspective. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 2013;35(2):125-130.

- [Google Scholar]

- Barriers to contraception among HIV-positive women in a periurban district of Uganda. Int J STD AIDS. 2012;23(9):661-666.

- [Google Scholar]

- Longitudinal study of correlates of modern contraceptive use and impact of HIV care programmes among HIV concordant and serodiscordant couples in Rakai, Uganda. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2014;40(3):208-216.

- [Google Scholar]

- Delayed entry to care by men with HIV infection in Kumasi, Ghana. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;22:107.

- [Google Scholar]

- Modern contraceptive use among women living with HIV/AIDS at the Korle Bu Teaching Hospital in Ghana. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;141(1):26-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Power and Politics in International Funding for Reproductive Health:The US Global Gag Rule. Reproductive Health Matters. 2004;12(24):128-137.

- [Google Scholar]

- Trend in the use of modern contraception in sub-Saharan Africa:Does women's education matter? Contraception. 2014;90(2):154-161.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of Contraceptive use Among Female Adolescents in Ghana. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2014;18(1):102-109.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2017. UNAIDS Data Sheet. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/20170720_Data_book_2017_en.pdf