Translate this page into:

Birth Preparedness Plans and Status Disclosure Among Pregnant Women Living with HIV Who are Receiving Antiretroviral Therapy in Ibadan, Southwest, Nigeria

* Corresponding author email: margaretakinwaare@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background:

Promoting the maternal health of pregnant women who are living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV; [PWLH]) is key to reducing maternal mortality and morbidity. Thus, inadequate birth preparedness plans, non-institutional delivery, and status concealment among PWLH contribute to the spread of HIV infection and threaten the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT). Therefore, this study aimed to assess the birth preparedness plan and status disclosure among PWLH, as well as the prevalence of HIV infection among pregnant women.

Methods:

The study adopted a descriptive cross-sectional research design; a quantitative approach was used for data collection. Three healthcare facilities that represented the three levels of healthcare institutions and referral centers for the care of PWLH in the Ibadan metropolis were selected for the recruitment process. A validated questionnaire was used to collect data from 77 participants within the targeted population. Ethical approval was obtained prior to the commencement of data collection.

Results:

The prevalence rate of HIV infection among the participants was 3.7%. Only 37.1% of the participants had a birth preparedness plan. A total of 40% of the participants tested for HIV, because testing was compulsory for antenatal registration. Only 7.1% of the participants had their status disclosed to their partners. Although 90% of the participants proposed delivering their babies in a hospital, only 80% of these participants had their status known in their proposed place of birth.

Conclusion and Global Health Implications:

The prevalence of HIV infection among pregnant women is very low, which is an indication of improved maternal health. However, the level of birth preparedness plan and status disclosure to partners are equally low, and these factors can hinder PMTCT. Institutional delivery should be encouraged among all PWLH, and their HIV status must be disclosed at their place of birth.

Keywords

HIV

PMTCT

Pregnancy

Maternal Health

Antenatal Care

1. Background and Introduction

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can be transmitted from an HIV-positive woman to her child during pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding. This mother-to-child transmission accounts for most infections in children.1 If a pregnant woman is living with HIV without treatment, the likelihood of the virus passing from mother to child is 15% to 45%. However, antiretroviral treatment (ART) and other interventions can reduce the risk to below 5%.2 Meanwhile, HIV continues to be a major cause of maternal and infant mortality and morbidity in sub-Saharan Africa.3,4,5 However, prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV strategies has proven to be effective in decreasing the number of children infected in utero, intrapartum, and during the breastfeeding period, with significant potential for improving maternal and child health.6

Nigeria, along with 22 other countries around the world (the vast majority of which are in sub-Saharan Africa), contributes 73% of the global women infected with HIV. Hence, the prevalence of HIV infection among pregnant women in these countries could rise. Thus, Nigeria is classified as a high priority for PMTCT.7 Therefore, adequate PMTCT services are needed in Nigeria to prevent HIV infections among pregnant women and children.8 These PMTCT services include access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) by PWLH, an adequate birth preparedness plan, institutional delivery, and counseling on HIV status disclosure.

The birth preparedness plan was recommended by the WHO as part of the package of essential services for high-quality care for PWLH.9 The birth preparedness plan encompasses an adequate birth plan, post-partum follow-up plan, breastfeeding plan, family planning plan, and breastfeeding plan. This birth preparedness plan is expected to be documented and discussed between the skilled care providers and the client. It also ensures institutional delivery, which eventually can be used to promote PMTCT and improve maternal health. However, several barriers to PMTCT have been observed in sub-Saharan Africa. These barriers commonly relate to the implementation of the recommended package of essential services for high-quality care for PWLH. Individual, social, and structural factors are all important determinants of PMTCT success, with stigma, difficulties with partner disclosure, perceived compulsory testing, confidentiality issues, and inadequate counseling being considered as major themes in recent studies.10

Studies have shown that disclosure of one’s HIV status is important in the prevention of HIV transmission, the early treatment and care of partners, and improved retention in PMTCT and ART programs.11 Also, it is acknowledged that the disclosure of one’s HIV status is complex, and therefore, healthcare providers who are working with PWLH need to give appropriate counseling, support, and skills that will enable PWLH to share results with their partners or significant others.12 The prevalence of HIV disclosure to partners varies between settings and populations.11 Studies from developed countries reported a very high level of HIV status disclosure,13 while the level is lower in sub-Saharan Africa.14,15 However, women reported fear of disclosure due to fear of being rejected and abandoned, fear of being blamed, fear of being considered unfaithful, fear of physical abuse, fear of divorce, stigma, and fear of violence from partners as barriers to disclosure.11

Therefore, the researchers sought to identify information on the prevalence of HIV infection among pregnant women, as well as status disclosure among PWLH, considering that many interventions which have been implemented to improve status disclosure to reduce the spread of the infection and to improve PMTCT. Also, there is a dearth of information on the level of birth preparedness plans among PWLH. Hence, there is a need to have such information to be able to plan interventional programs that will further ensure PMTCT in Nigeria.

1.1. Objective of the Study

This study aimed at assessing the following factors among PWLH:

-

Birth preparedness plan among pregnant women living with HIV who are receiving antiretroviral therapy;

-

Status disclosure among pregnant women living with HIV who are receiving antiretroviral therapy; and

-

Prevalence of HIV infection among pregnant women receiving skilled antenatal care in selected hospitals.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Setting

Three healthcare facilities, representing the three levels of care (i.e., primary, secondary, and tertiary) and as the referral centers for the care of pregnant women living with HIV in the Ibadan metropolis, Oyo State, Southwest Nigeria, were selected for respondent recruitment. These healthcare facilities were the Primary Health Center, Agbongbon; Adeoyo Maternity Teaching Hospital (AMTH); and University College Hospital, all located in Ibadan. Ibadan comprises all major tribes in Nigeria – Hausa, Igbo, and Yoruba, but the predominant tribe is the Yoruba ethnic group.

2.2. Study Design

The researchers adopted a descriptive cross-sectional study design, and a quantitative approach was used for data collection. This study was designed to assess the status disclosure and birth preparedness plan among pregnant women living with HIV who were receiving antiretroviral therapy in Ibadan.

2.3. Study Population

Pregnant women living with HIV who have registered for antenatal care and were receiving the antiretroviral drug at the selected healthcare facilities were recruited for the study.

2.4. Sampling Technique

Three healthcare facilities that represented the three levels of healthcare in Nigeria and had facilities for PMTCT care, which were supported by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), were purposively selected for the study. Likewise, all registered pregnant women at the PEPFAR clinic during the period of data collection were purposively recruited for the study.

2.4.1. Sample size calculation

Based on the proportion of HIV infection among pregnant women in a previous study in Nigeria (Charan et al.16), the following formula was used in calculating the sample size:

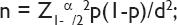

n = sample size;

Z1-α/2 = standard normal variate = 1.96 (at 5% type 1 error);

p = Expected proportion in population based on previous studies or pilot study = 4.8% (Anyaka et al., 2016);

d = absolute error or precision = 5%;

n = 70.

2.5. Instrument

The researchers adopted a semi-structured/structured questionnaire from the Monitoring Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness (BPCR) Tools and Indicators for Maternal and Newborn Health developed by the Johns Hopkins Program for International Education in Gynecology and Obstetrics (JHPIEGO)17 and the “Package of Essential Services for Pregnant Women Living with HIV by the World Health Organization. 9 The instrument was modified by the authors following a rigorous review of the literature based on relevance to the study and the study setting.

Validity and Reliability of Instrument: The Monitoring BPCR instruments and indicators for maternal and newborn health, and the Package of essential services for pregnant women living with HIV were transformed into a validated instrument (that is a semi-structured/structured questionnaire). Researchers, clinicians (practitioners), and statisticians in the fields of reproductive, maternal, and child health collaborated to modify the instrument. The instrument was also revised based on reviewers’ feedback and outcomes from the pilot test. The reliability of the instruments was conducted to assess the psychometric properties and ensure the adaptability of the instrument to the study setting. A test-retest-reliability test was conducted. The results of the reliability tests were found to be 0.8. Hence, the instrument was deemed reliable.

2.6 Procedure for Data Collection

The researcher and the two trained research assistants visited the study site and related the objectives of the study to the PEPFAR staff. The arrangement was made on how to use the PMTCT support group platform for targeted participant recruitment. The participants were informed of the objectives of the study. The interviewer-administered questionnaire was administered face-to-face to the participants. Respondents were guided by the researcher and trained research assistants in the questionnaire completion.

2.7. Method of Data Analysis

A preliminary quality check of the questionnaires was performed for errors. The data were cleaned, coded, and entered into Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22 (IBM). Frequency and percentages were used to summarize the results of the descriptive statistics. Mean and standard deviation were used to summarize continuous variables. Tables and Figures were used in presenting some of the results. The statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The study was approved by the University of Ibadan/University College Hospital (UI/UCH) Ethics Review Committee and the Oyo State Ethics Review Committee. The study objectives and the research purpose were explained to the participants. Participants voluntarily accepted participation and gave informed consent. Participants were assured of the confidentiality of the information they provided as part of the study.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographic Characteristics

Most of the participants who participated in the study were less than 40 years of age. The age range of the respondents was 30-39 years (60%), while the mean age was 34 years + 5.8 Standard Deviation (SD). Only 1.4% of the participants were teenagers, while 15.7% of the participants were older than 40 years. Most of the participants had formal education (47.1%) and received secondary school education and/or tertiary education (52.9%). Most participants had a previous pregnancy experience, while 15.7% of the participants were experiencing pregnancy for the first time. The percentage of the participants who registered for antenatal care in the third trimester was slightly more than their counterparts who registered in the second trimester (45.7% vs. 44.3%), respectively. Table 1 shows details of the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents.

| Socio-demographic characteristics | Frequency (N = 70) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||

| less than 20 years | 1 | 1.4 |

| 20-29 years | 16 | 22.9 |

| 30-39 years | 42 | 60.0 |

| 40-49 years | 11 | 15.7 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 3 | 4.3 |

| Married | 66 | 94.3 |

| Separated | 1 | 1.4 |

| Highest level of education attained | ||

| No formal education | 3 | 4.3 |

| Primary school | 4 | 5.7 |

| Secondary school | 33 | 47.1 |

| Tertiary | 30 | 42.9 |

| Religion | ||

| Christianity | 43 | 61.4 |

| Islam | 27 | 38.6 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Yoruba | 60 | 85.7 |

| Other | 10 | 14.3 |

| Occupation | ||

| Trading | 42 | 60.0 |

| Artisan | 14 | 20.0 |

| Civil servants | 9 | 12.9 |

| Student | 2 | 2.9 |

| Unemployed | 2 | 2.9 |

| No response | 1 | 1.4 |

| Income (#) | ||

| No income | 1 | 1.4 |

| 1-30,000 | 41 | 58.6 |

| 31,000-60,000 | 15 | 21.4 |

| 61,000 – 90,000 | 2 | 2.9 |

| 91,000 – 120,000 | 2 | 2.9 |

| 121,000 – 150,000 | 7 | 10.0 |

| No response | 2 | 2.9 |

| Gravidity (Number of Pregnancy) | ||

| Primigravida (one Pregnancy) | 11 | 15.7 |

| Multigravida (more than one pregnancy) | 59 | 84.3 |

| Estimated Gestational age at antenatal registration | ||

| First trimester | 7 | 10.0 |

| Second trimester | 31 | 44.3 |

| Third trimester | 32 | 45.7 |

3.2. Birth Preparedness Plans

In all, 90.0% of the participants had identified a healthcare facility, either a private or public, as their proposed site of delivery and preparation for birth. However, 20% of the participants chose to have their delivery at a healthcare facility where their HIV status was unknown. A total of 82.9% and 62.9% of the participants had post-partum follow-up plans and family planning strategies, respectively. Also, 51.4% of the participants reported having a birth plan, but only 20% of the participants documented their plan as reported. Overall, 37.1% of the participants had a good birth preparedness plan (Table 2).

| Birth preparedness plan | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Good | 26 | 37.1 |

| Poor | 44 | 62.9 |

3.3. HIV Disclosure Status

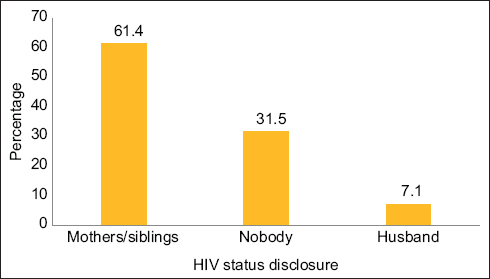

The study found that 40.0% of the participants tested for HIV because it was compulsory for antenatal registration. However, 14.3% reported that they voluntarily tested for HIV and were aware of their status before antenatal registration (Figure 1). We found that 61.4% of the participants disclosed their HIV status to either their mothers or siblings, while 7.1% of them disclosed their status to their husbands/partners (Figure 2).

- Reasons for HIV screening/testing among participants

- HIV status disclosure among participants

3.4. Prevalence of HIV Infection

Table 3 shows the number of antenatal registrations and the number of HIV-positive women enrolled from April 2021 to March 2022 across the three levels of healthcare institutions. A total of 1,375 pregnant women enrolled for antenatal care at the University College Hospital (UCH); and 120 of them were HIV positive. About 3,158 pregnant women enrolled for antenatal care at Adeoyo Maternity Teaching Hospital (AMTH) during the same period; 70 of them were HIV positive after testing. Lastly, 963 pregnant women enrolled for antenatal care at the Primary Healthcare Center, Agbongbon, during the same period, and only 12 of them were found to be HIV positive after testing. Therefore, a total of 5,496 pregnant women enrolled for antenatal care at the selected healthcare facilities, and 202 of them tested HIV positive during the study.

| Month/Year | UCH | AMTH | PHC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANC Registration | HIV Treatment Enrolment | ANC Registration | HIV Treatment Enrolment | ANC Registration | HIV Treatment Enrolment | |

| April 2021 | 116 | 11 | 239 | 8 | 88 | 1 |

| May 2021 | 28 | 12 | 226 | 7 | 83 | 1 |

| June 2021 | 111 | 8 | 246 | 5 | 87 | 1 |

| July 2021 | 120 | 2 | 245 | 5 | 84 | 1 |

| August 2021 | 94 | 11 | 242 | 5 | 85 | 1 |

| September 2021 | 96 | 9 | 294 | 2 | 67 | 1 |

| October 2021 | 124 | 10 | 257 | 5 | 71 | 0 |

| November 2021 | 129 | 10 | 255 | 6 | 92 | 1 |

| December 2021 | 159 | 7 | 293 | 6 | 68 | 1 |

| January 2022 | 156 | 12 | 250 | 10 | 77 | 1 |

| February 2022 | 135 | 14 | 293 | 6 | 88 | 2 |

| March 2022 | 107 | 14 | 318 | 5 | 73 | 1 |

| TOTAL | 1375 | 120 | 3158 | 70 | 963 | 12 |

Data source: Records from University College Hospital, Adeoyo Maternity Teaching Hospital, and Primary Healthcare Centre, Agbongbon.

The prevalence of HIV infection was 3.7%. To derive the prevalence, the number of people in the sample with the characteristic of interest was divided by the total number of people in the sample and multiplied by 100. Based on our study, the total number of new cases was 202; the total population was 5,496.

4. Discussion

This study reported that one-tenth of the participants who participated in this study proposed to have their childbirth outside of a healthcare facility. However, one-fifth of the participants did not disclose their HIV status at their proposed place of birth. The results are worrisome because most non-institutional deliveries in Nigeria do not have skilled birth attendants.18 Hence, this factor may contribute to increases in the spread of HIV infection and mother-to-child transmission. More so, this category of women who proposed to deliver outside the hospital did not disclose their HIV status at their proposed place of birth. HIV testing is not guaranteed in almost all non-institutional deliveries in Nigeria. Hence, both the birth attendants and newborns could be infected with HIV in the process of childbirth. Therefore, interventions, programs, counseling, and other efforts that ensure institutional delivery for all PWLH in Nigeria and other developing countries are recommended.

After assessing the overall birth preparedness plan of the participants who received ART, the result showed that most of the participants had poor birth preparedness plans, which implies that many of the participants may have unplanned home delivery. Unplanned home delivery has been linked to inadequate birth preparedness.20 Unplanned home delivery could further increase the spread of HIV through mother-to-child transmission, and PMTCT may not be achieved. Also, less than half of the participants had good birth preparedness, which could be due to poor knowledge and low income, since most of the participants were petty traders and artisans who could not afford to adequately prepare for birth. Although there is limited information in the literature about birth preparedness plans among PWLH, studies20,21 conducted among pregnant women in Nigeria reported low birth preparedness. Hence, there is a need for integrating BPCR education into routine prenatal education, especially counseling of PWLH. More importantly, documentation of birth preparedness plans among PWLH could yield a better pregnancy outcome and further strengthen PMTCT.

The study findings show that a higher percentage of the participants tested for HIV because testing was compulsory for antenatal registration. However, the least percentage was recorded by those who did voluntarily test for HIV; they were aware of their status before antenatal registration. In this study, antenatal registration was the most influential factor regarding the decision for HIV testing during pregnancy, since testing was a criterion for antenatal registration. This finding implies the importance of antenatal registration with a skilled care provider in healthcare facilities to conduct PMTCT. This finding is also supported by Ejigu et al.22 who described HIV testing at antenatal registration as an entry point to PMTCT and therefore recommended integrating HIV testing into antenatal care services. This finding is also consistent with findings in a previous qualitative study in Sudan.23 Thus, training and sensitizing antenatal care providers to promote HIV testing at antenatal registration will facilitate care provider-initiated HIV testing among pregnant women, thereby promoting PMTCT.

Disclosure of HIV status promotes access to care, PMTCT, and ART adherence, especially among pregnant women.11 The methods are entry points for successful ART treatment. In this study, more than half of the participants had disclosed their HIV status to either their mothers or siblings. However, less than one-tenth of the participants disclosed their status to their spouses. Spousal disclosure is associated with increased support, including support for regular clinic attendance and ART adherence.24,25 Although relatively uncommon, lack of disclosure and fear of stigma were major barriers to ART adherence. Some women may not disclose their status for fear of losing support from their partners. This finding corresponds with a qualitative study in a similar setting where the fear of disclosure among HIV-positive women was influenced by their economic dependency on men, among other factors.26

A previous study identified the largest barrier to spousal disclosure, which was fear of negative outcomes, especially divorce. Disclosure is a process that requires preparedness and time, as described in the process-oriented framework or disclosure processes model.27 It is thus, not surprising that disclosure increased over time.28 Similar to previous studies performed in the general population, women in this study had better disclosure to their spouses, mothers, and sisters as opposed to their fathers and brothers.28 The spousal disclosure in this study was low when compared to disclosure to mothers and sisters or other family members. This finding is contrary to another study in Nigeria, which showed that two third of the participants disclosed their HIV status to their partners following antenatal HIV testing.29,30 Therefore, disclosure of HIV status to partners will promote spousal support. This finding is also supported by Chirambo et al.31 Spousal support could be in the form of transportation and ART reminders, which may enhance medication adherence.

Similarly, having a sexual partner who has been tested makes it easier for women to disclose their HIV status.30, 32 Interventions to enhance HIV status disclosure and partner support should address women’s fears and support for partner testing. These interventions may include efforts to foster family support groups. Batte et al.30 reported that women made various attempts to disclose and encourage their partners for testing, with varying levels of success. A spousal test could be a point of intervention for PMTCT services, as spousal disclosure increases women’s participation in PMTCT programs.33 In addition to improving PMTCT programs, disclosure, and partner testing at antenatal registration may support care for HIV-infected partners.

This study showed a low prevalence of HIV among pregnant women who received skilled antenatal care. The finding further stresses the importance of receiving skilled care during pregnancy. Antenatal care visits strengthen data collection that will be used for informing necessary interventions for positive pregnancy outcomes. The low prevalence of HIV among participants in this study is similar to what was found in meta-analysis data from 19 African studies.34 However, the prevalence in this current study was approximately one-third compared to what was found in another study in Nigeria, which was 13 years before this current study.35 The finding implies that the prevalence is decreasing with increasing years in Nigeria. Nonetheless, the identified prevalence in this study was higher and even double the prevalence in another study36 conducted in Lesotho, despite Lesotho being a country with a high burden of HIV infection among women of reproductive age. Therefore, much needs to be done to reduce HIV infection among pregnant women in Nigeria.

5. Conclusion and Global Health Implications

The main reason for HIV testing among the participants was antenatal registration, which was one of the successes of the integration of HIV screening into antenatal care. The HIV prevalence among the participants was low, and efforts should be made to sustain this. However, the birth preparedness plan among the participants was low, the level of status disclosure to partners was low, and not all the participants proposed to deliver their babies to the hospital where their HIV status was known. These decisions may potentially militate against PMTCT and HIV transmission. Therefore, interventions to improve PMTCT among PWLH are recommended at all levels of healthcare institutions.

5.1. Limitations of the Study

This study has a number of limitations. The researchers had a limited study period; hence, they could not recruit many participants for the study. This factor also limited the data analysis. Therefore, a large sample size is suggested for further studies.

Acknowledgments:

We appreciate the support of the University of Ibadan Medical Education Partnership Initiative Junior-faculty (UI-MEPI-J), funded by the National Institute of Health (NIH), USA. We sincerely appreciate Profs. Adesola Ogunniyi and Georgina Odaibo for providing intellectual guidance and opportunity to benefit from the research award. Also, we appreciate the support of the Director of the Institute of Infectious Diseases in the College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Dr. O.A. Awolude, and other staff from the institute for their support during data collection for the study. Special thanks to all the staff of PEPFAR clinic, Adeoyo Maternity Teaching Hospital, for their support during the period of data collection.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

Financial Disclosure: Nothing to declare.

Funding: The study was supported by the University of Ibadan Medical Education Partnership Initiative Junior-faculty (UI-MEPI-J), funded by the National Institute of Health (NIH), USA. The project described was supported by Award Number D43TW010140 from the Fogarty International Center, NIH.

Ethics Approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Ibadan/University College Hospital Ethics Committee with registration number: NHREC/05/01/2008a and assigned number UI/EC/22/0030. The study also obtained approval from the Oyo state Ethics Review Committee with reference number: AD 13/479/44262. Informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- UNAIDS Report. Published August 1, 2022 https://www.unaids.org/en/keywords/preventing-mother-child-transmission

- A cross-sectional, population-based study measuring comorbidity among people living with HIV in Ontario. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:161. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-161

- [Google Scholar]

- Maternal HIV status associated with under-five mortality in rural Northern Malawi:a prospective cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68(1):81-90. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000000405

- [Google Scholar]

- Morbidity and mortality in HIV-exposed under-five children in a rural Malawi setting:a cohort study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17(4 Suppl):19696. doi:10.7448/IAS.17.4.19696

- [Google Scholar]

- 2017. Bahamas Ministry of Health. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/BHS_2017_countryreport.pdf

- 2018. UNAIDS. Accessed September 21, 2022 https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/unaids-data-2018_en.pdf

- Awareness, attitudes and perceptions regarding HIV and PMTCT amongst pregnant women in Guinea-Bissau–a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health. 2017;17(1):71. doi:10.1186/s12905-017-0427-6

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors associated with HIV status disclosure to partners and its outcomes among HIV-positive women attending Care and Treatment Clinics at Kilimanjaro region, Tanzania. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(3):e0211921. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0211921

- [Google Scholar]

- Facilitating HIV status disclosure for pregnant women and partners in rural Kenya:a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1115. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-1115

- [Google Scholar]

- Female disclosure to HIV positive serostatus to sex partners in Hawaii and Washington, USA. Women Health. 2010;50(6):506-26. doi:10.1080/03630242.2010.516697

- [Google Scholar]

- Disclosure of HIV seropositive status to sexual partners and its associated factors among patients attending antiretroviral treatment clinic follow up at Mekelle Hospital, Ethiopia:a cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:109. doi:10.1186/s13104-015-1056-5

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of early HIV status disclosure in retention in HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29(1):646-650. doi:10.1089/apc.2015.0205

- [Google Scholar]

- How to calculate sample size for different study designs in medical research? Indian J Psychol Med. 2013;35(2):121-126. doi:10.4103/0253-7176.116232

- [Google Scholar]

- JHPIEGO 2004

- Availability of skilled birth attendance during home delivery among postpartum women in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr J Nurs Midwifery. 2014;5(2):67-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determinant of choice of place of birth and skilled birth attendant among childbearing women in Ibadan, Nigeria. African Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health. 2015;9(3):121-124. doi:10.12968/AJMW.2015.9.3.121

- [Google Scholar]

- Birth preparedness and complication readiness among pregnant women attending antenatal classes at primary health center in Ibadan, Nigeria. Open J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;9:1358-1364.

- [Google Scholar]

- Birth preparedness and complication readiness among pregnant women in a secondary health facility in Abakaliki, Ebonyi State, Nigeria. BioMed Res Int. 2020;2020:9097415. doi:10.1155/2020/9097415

- [Google Scholar]

- HIV testing during pregnancy for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0201886. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201886

- [Google Scholar]

- Perceptions of Sudanese women of reproductive age toward HIV/AIDS and services for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:674. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-2054-1

- [Google Scholar]

- HIV status disclosure and associated outcomes among pregnant women enrolled in antiretroviral therapy in Uganda:a mixed methods study. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):107. doi:10.1186/s12978-017-0367-5

- [Google Scholar]

- Retention in HIV care during pregnancy and the postpartum period in the option B+era:systematic review and meta-analysis of studies in Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;77(5):427-438. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000001616

- [Google Scholar]

- 'Making the most of our situation':a qualitative study reporting health providers'perspectives on the challenges of implementing the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV services in Lagos, Nigeria. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e046263. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046263

- [Google Scholar]

- Pediatric HIV disclosure:a process-oriented framework. AIDS Educ Prev. 2013;25(4):302-14. doi:10.1521/aeap.2013.25.4.302

- [Google Scholar]

- Disclosure of HIV serostatus among pregnant and postpartum women in sub-Saharan Africa:a systematic review. AIDS Care. 2015;27(4):436-50. doi:10.1080/09540121.2014.997662

- [Google Scholar]

- A mixed-methods assessment of disclosure of HIV status among expert mothers living with HIV in rural Nigeria. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0232423. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0232423

- [Google Scholar]

- Disclosure of HIV test results by women to their partners following antenatal HIV testing:a population-based cross-sectional survey among slum dwellers in Kampala Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:63. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-1420-3

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors influencing adherence to antiretroviral treatment among adults accessing care from private health facilities in Malawi. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1382. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7768-z

- [Google Scholar]

- HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partner:a survey among women in Tehran, Iran. Eur J Med Res. 2022;27(1):56. doi:10.1186/s40001-022-00663-6

- [Google Scholar]

- HIV status disclosure and associated outcomes among pregnant women enrolled in antiretroviral therapy in Uganda:a mixed methods study. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):107. doi:10.1186/s12978-017-0367-5

- [Google Scholar]

- Incident HIV during pregnancy and postpartum and risk of mother-to-child HIV transmission:a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11(2):e1001608. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001608

- [Google Scholar]

- HIV prevalence and trends among pregnant women in Abuja, Nigeria:a 5-year analysis. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;32(1):82-89.

- [Google Scholar]

- HIV incidence among pregnant and postpartum women in a high prevalence setting. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0209782. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0209782

- [Google Scholar]