Translate this page into:

Epidemiology of Opportunistic Infections in HIV Infected Patients on Treatment in Accredited HIV Treatment Centers in Cameroon

*Corresponding author email: ngwayuclaude1@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background:

The African continent accounts for over 70% of people infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). The HIV sero-prevalence rate in Africa is estimated at 4.3%. In developed countries, such as France, pneumocystis is indicative of AIDS in 30% of patients; however, in Africa, pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) is the most-documented opportunistic infection (OI) and the leading cause of death in HIV-infected patients. In 2016, Cameroon had 32,000 new cases of OI and 29,000 deaths as a result of these infections. However, there is little existing data on the epidemiological profile of OIs in Cameroon, which is why we conducted this study in accredited HIV treatment centers and care/treatment units in the two cities of Douala and Yaounde, Cameroon.

Methods:

This was a retrospective descriptive and analytical study carried out in 12 accredited HIV treatment centers in the cities of Yaoundé and Douala, Cameroon, over a period of seven months from October 2017 to April 2018. A stratified sampling method was used with three sampling levels: the city, type of health facility and size of active files. Ethical clearance and administrative authorization were obtained from the appropriate authorities and data were collected using a pre-tested survey form. The data collected was entered and analyzed using Epi Info version 3.5.4.

Results:

Out of a total of 1,617 HIV-infected patients sampled, 419 (25.9%) had at least one OI. Of these patients with an OI, 246 or 65% had a baseline CD4 count of <200/mm3. There was a significant relationship between the male gender and the onset of OI (OR = 1.47; p = 0.01). Age ≥ 50 years was associated with the occurrence of OI (OR = 2.57; p = 0.01). A CD4 count of <200/mm3 was also associated with the risk of developing an OI (OR = 3.12; p = <0.01).

Conclusion and Global Health Implications:

The prevalence of OI is high among people living with HIV (25.9%). Shingles was the most common OI found followed by pulmonary tuberculosis. Male gender, age ≥ 50 years, and CD4 <200/mm3 were the most common factors associated with the occurrence of these OI. These findings suggest that public health interventions for reducing HIV related co-morbidities (and implicitly mortality) should especially target the male gender for greater impact in addition to other measures.

Keywords

Opportunistic infections

HIV/AIDS

Cameroon

AIDS treatment centers

ATC

UPEC

Tuberculosis

Shingles

1. Background

The discovery of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) dates back to 1981 when young gay American adults began developing opportunistic infections (OI).1 Infections such as pneumocystis and Kaposi sarcoma were common among patients with a weakened immune system. In 1983, Professor Luc Montagnier, in collaboration with Professor Françoise Barré-Sinoussi and Professor Robert Gallo in the United States identified the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) as the pathogen responsible for AIDS.2,3

Since the 1990s, the HIV/AIDS pandemic has been on a rapid increase, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. According to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), in 2016, one million people died of OI out of the 36.7 million living with HIV.3

An OI is an infection caused by a microorganism that is often present in the environment or even in the body, but cannot cause a disease as long as the immune system is preserved. When this immune system becomes compromised, the microorganism seizes the “opportunity” to develop and cause the occurrence of an infection.4 Most AIDS-related deaths result from these OIs which are often caused by parasites, bacteria, fungi and other viruses.5 The classification of HIV patients into clinical stages, as proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO), takes into consideration different OI some of which include: seborrheic dermatitis, shingles, respiratory tract infections, oral candidiasis, oral hairy leukoplakia, pulmonary tuberculosis, severe bacterial infections, pneumocystis, recurrent bacterial pneumonia, cerebral toxoplasmosis, cryptosporidiosis and chronic isosporosis, extrapulmonary cryptococcosis, Kaposi sarcoma, extrapulmonary tuberculosis among others.6 Among the most common AIDS-defining OIs in Latin America, tuberculosis (TB) accounted for 31%, followed by pneumocystis, which accounted for 24%.7 In Africa, pulmonary tuberculosis is the leading cause of death in HIV-infected patients.8 In France, pneumocystis is indicative of AIDS in 30% of patients followed by esophageal candidiasis, which accounts for 22%.8 In Ethiopia, the prevalence of opportunistic infection was found to be 33.6% among HIV patients in the nation’s capital, Addis Ababa.9

In Cameroon, the seroprevalence rate of HIV is estimated at 4.7% according to the results published by the Demographic and Health Survey and the Multiple Indicators Survey (DHS-MICS 2016).10 The National AIDS Control Committee (NACC) 2016 report indicates that Cameroon has opted for UNAIDS target 90-90-90 by 2020. This means that 90% of people infected with HIV should know their HIV status; 90% of HIV-positive people should have access to HIV care and treatment; and that 90% of the patients on treatment should have a suppressed viral load (<1000 copies/mm). An epidemiological report published by NACC in 2018 showed that 268,939 patients were on anti-retroviral treatment (ART) as of June 2018 compared to the 253,343 at the end of December 2017.11 However, to achieve the 90-90-90 target, a minimum of about 421,256 out of 520,069 people living with HIV (PLWHIV) should have been on treatment by December 2018, According to the same report, 70.7% of those who had done a viral load were virally suppressed while 29.3% had virologic failure.

These patients with virologic failure are, therefore, likely to develop opportunistic infections (OIs). In the same report, the authors mention HIV-TB co-infection and cotrimoxazole prophylaxis, but nothing is said about the situation of all OIs among PLWHIV in Cameroon. Yet, it is OIs that are responsible for the high number of deaths among PLWHIV.

We, therefore, decided to describe the epidemiological profile of OIs in HIV-infected patients followed up in accredited treatment centers (ATCs) and care units (UPEC) in Yaoundé and Douala. Having an in-depth understanding of the epidemiology of opportunistic infections among PLWHIV will enable us to understand the magnitude of the problem. This information will serve as a guide to policy makers when formulating policies and allocating resources to improve the quality of life of PLWHIV and reduce AIDS related mortality.

1.1. Study Objectives

The objective of this study was to describe the profile of OIs among PLWHIV in Yaounde and Douala— the two major cities with greatest burden of HIV in Cameroon. Specifically, we set out to describe the profile (age, sex, profession, level of education) of PLWHIV presenting with OIs, determine the relative frequency of the types of OIs among this group of persons and determine the factors associated with OIs among PLWHIV.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study was a retrospective descriptive and analytical study carried out within a period of seven months in 12 accredited HIV care and treatment centers (ACTs) in the cities of Yaoundé and Douala, Cameroon. We used a stratified sampling method with 3 sampling levels: the city, type of health facility and size of active files. The cities were selected based on convenience while 12 out of the 38 accredited care and treatment units (ACT) were selected randomly with the probability of selection proportionate to size. The number of ACTs were limited at 12 for convenience. We reviewed patient files spanning from January to December 2014 and our analysis was conducted from October 1, 2017 to April 30, 2018.

2.2. Study Population

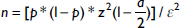

Our study population was HIV-positive patients followed up in accredited treatment centers and care units in the cities of Yaounde and Douala. We included all the files of patients who tested positive for HIV in 2014 in the selected treatment centers irrespective of the serotype and whether the patient was on antiretroviral therapy or not. We excluded patient files that did not carry information on date of HIV diagnosis, medical consultation and basic demographic information such as age and sex. We also excluded patients that were transferred from another health facility without a file. The calculation of the sample size was done using the formula below. There were no prevalence studies from the population of interest in Cameroon, therefore, we used the prevalence rate of 48% from a study in Ethiopia with a determined margin of error of 2.5%. Based on this, we determined our minimum sample size to be 1,534.

2.3. Sampling Technique

From the 38 accredited treatment centers and care/treatment units, selection of study participants was done using a stratified sampling method with 3 sampling levels: city (Yaounde or Douala), type of health institution (public/private) and the number of active files. The number of active files in each site was considered small if it was less than or equal to 978, which was the median number of active files in the different sites. For convenience, we selected 12 treatment sites offering antiretroviral treatment in the two cities that had been selected (Yaoundé and Douala). The treatment sites were selected randomly with the probability of selection proportionate to size.

2.4. Data Collection and Analysis

After obtaining all required authorizations, we started by testing our questionnaire in a treatment center that did not participate in the study. This was done at the HIV treatment unit of Cité Verte District Hospital, Yaoundé and all challenges encountered with the questionnaire were addressed. To determine the probing step in each site we divided the cohort by the sample size of the site. Then we selected the patients’ files by sampling, respecting the sampling rate defined for each site until the sample size was reached for the chosen site. For example, when the probing step was 6, we randomly chose a number between one and six. The random number was considered the first record in the study. Subsequently, we added six to this number to get the number of the next file, then six to the number of the next file, and so on. If for one reason or another a file was not in place, the next file was taken without changing the pre-established order thereafter. In addition, when searching for information in the medical file, we verified its validity in terms of completeness of data by taking into account the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Every patient file that was selected was studied from the date of opening to the last consultation and any diagnoses of OIs made by the physicians were considered. Patients were said to be symptomatic according to WHO criteria.27 Records of deceased patients were also exploited. The data collected were entered and analyzed with Epi Info version 3.5.4 (CDC, Atlanta, USA, 2012). Qualitative variables were expressed as percentages while quantitative variables were expressed as medians, means and standard deviation for the assessment of its centrality. The chi-square test was used to compare the percentages and corrected by the Fischer test when the applied conditions were not valid. The means were compared through the student test.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographic Characteristics of the Study Population

We sampled a total of 1,617 subjects in this study and women accounted for 71.2% (1,152). The average age of our participants was 41.27 ± 10.17 years with an age range of 20 to 82years old (table 1). Forty four percent (711) of the subjects were single while 28.3% were married. Fifty seven percent of the study participants had received education up to secondary level while 27% were business men and women (table 2).

| Age range (in years) | Sex | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male % | Female % | ||

| 20-29 | 23 (13.1) | 152 (86.9) | 175 |

| 30-39 | 131 (21.8) | 470 (78.2) | 601 |

| 40-49 | 178 (35.1) | 329 (64.9) | 507 |

| ≥ 50 | 133 (39.8) | 201 (60.2) | 334 |

| Total | 465 (28.8) | 1152 (72.2) | 1617 |

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Level of Education | ||

| No formal education | 54 | 3.3 |

| Primary | 381 | 23.6 |

| Secondary | 922 | 57 |

| University | 260 | 16.1 |

| Profession | ||

| Housewife | 335 | 20.7 |

| Civil servant | 229 | 14.2 |

| Student | 132 | 8.2 |

| Trader | 435 | 26.9 |

| Others | 486 | 30.1 |

3.2. Clinical Characteristics of the Study Population

Eight hundred and ninety-two of our study participants (55.2%) had discovered their HIV serological status after a clinical suspicion by a health care provider while 31.8% were diagnosed during voluntary counselling and testing (table 3). Six hundred and thirty-eight participants (44.2%) had a baseline CD4 count of less than 200 copies/mm3. In addition, 459 had a recent viral load result with 260 (56.6%) of them being less than 50 copies/mm3 (table 4). The majority of the participants, 1215 (75.2%) were on WHO’s first line regimen.

| Circumstances of HIV diagnosis | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Provider initiated testing and counselling (PITC) | 892 | 55.2 |

| Voluntary counselling and testing | 514 | 31.8 |

| Antenatal consultation (ANC) | 153 | 9.5 |

| Premarital counselling and testing | 12 | 0.7 |

| Blood donation | 2 | 0.1 |

| Others | 44 | 2.7 |

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| CD4 count on initiation | ||

| 0-199/mm3 | 638 | 44.2 |

| 200-349/mm3 | 470 | 32.6 |

| ≥ 350/mm3 | 334 | 23.2 |

| First viral load results from after initiation | ||

| 0-49 copies | 18 | 15.4 |

| 50-999 copies | 29 | 24.8 |

| ≥ 1000 copies | 70 | 59.8 |

| Most recent viral load result | ||

| 0-49 copies | 260 | 56.6 |

| 50-999 copies | 133 | 29.0 |

| ≥ 1000 copies | 66 | 14.4 |

3.3. Characteristics of Patients with at Least One Opportunistic Infection

A total of 419 participants had at least one OI, 65.2% of them were women, 42.7% were single, 35.1% were within the age range of 40 to 49 years and 78.7% (330) were on first-line antiretroviral (ARV) regimens (table 5). Two hundred and forty-six (60.6%) had a baseline CD4 count of less than 200 copies/mm3; and 123 had a recent viral load result with 53 (43%) of them being less than 50 copies/mm3 (table 6). The most common opportunistic infections found were shingles (25%), followed by pulmonary tuberculosis (20%) and oral candidiasis (12%) (table 7).

| Variables | Frequency (n) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 146 | 34.8 |

| Female | 273 | 65.2 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 20-29 | 28 | 6.7 |

| 30-39 | 137 | 32.7 |

| 40-49 | 147 | 35.1 |

| ≥50 | 107 | 25.5 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 119 | 28.4 |

| Widow/widower | 38 | 9.1 |

| Divorced | 16 | 3.8 |

| Single | 179 | 42.7 |

| Concubine | 67 | 16.0 |

| Level of Education | ||

| No formal Education | 15 | 3.5 |

| Primary | 111 | 26.5 |

| Secondary | 229 | 54.7 |

| University | 64 | 15.3 |

| Profession | ||

| Housewife | 91 | 21.7 |

| Civil Servant | 60 | 14.3 |

| Student | 33 | 7.9 |

| Trader | 113 | 27.0 |

| Others | 122 | 29.1 |

| Clinical stage | Clinical characteristics | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 n=1 (0.07%) | Persistent generalized lymphadenopathy | 1 | 0.1 |

| Stade 2 n=401 (29.08%) | Weight loss <10% | 186 | 13.5 |

| Herpes zoster | 130 | 9.4 | |

| Papular pruritic eruptions | 45 | 3.3 | |

| Recurrent oral ulcerations | 11 | 0.8 | |

| Sinusitis | 10 | 0.7 | |

| Onychomycosis | 8 | 0.6 | |

| Otitis | 2 | 0.1 | |

| Pharyngitis | 5 | 0.4 | |

| Seborrheic dermatitis | 4 | 0.3 | |

| Stade 3 n=879 (63.74%) | Weight loss >10% | 388 | 28.1 |

| Unexplained persistent fever >1 month | 158 | 11.5 | |

| Pulmonary TB | 104 | 7.5 | |

| Unexplained persistent diarrhea >1 month | 83 | 6.0 | |

| Oral candidiasis | 63 | 4.6 | |

| Lung infections | 50 | 3.6 | |

| Persistent anemia with HB<8g/dl | 30 | 2.2 | |

| Oral hairy leukoplakia | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Osteoarthritis | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Meningitis | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Stade 4 n=98 (7.10%) | Kaposi sarcoma | 30 | 2.2 |

| Cerebral toxoplasmosis | 25 | 1.8 | |

| Extrapulmonary TB | 20 | 1.5 | |

| Esophageal candidiasis | 7 | 0.5 | |

| Extrapulmonary cryptococcosis | 6 | 0.4 | |

| HIV encephalopathy | 5 | 0.4 | |

| Cachexic syndrome | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Pneumocystis | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Bacteria pneumonia | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Others | 2 | 0.1 | |

| Opportunistic infections | Sex | Frequency (N) | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||

| Shingles | 37 | 93 | 130 | 25.0 |

| Pulmonary tuberculosis | 41 | 63 | 104 | 20.0 |

| Oral candiasis | 21 | 42 | 63 | 12.1 |

| Respiratory tract infections | 19 | 31 | 50 | 9.6 |

| Prurigo | 14 | 31 | 45 | 8.6 |

| Kaposi sarcoma | 12 | 18 | 30 | 5.8 |

| Cerebral toxoplasmosis | 7 | 18 | 25 | 4.8 |

| Extrapulmonary tuberculosis | 8 | 12 | 20 | 3.8 |

| Sinusitis | 5 | 5 | 10 | 1.9 |

| Onychomycosis | 2 | 6 | 8 | 1.5 |

| Esophageal candidiasis | 5 | 2 | 7 | 1.3 |

| Pulmonary cryptococcosis | 3 | 3 | 6 | 1.2 |

| Pharyngitis | 2 | 3 | 5 | 1.0 |

| HIV encephalopathy | 2 | 3 | 5 | 1.0 |

| Seborrheic dermatitis | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0.8 |

| Otitis | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.4 |

| Oral hairy leukoplakia | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Osteoarthritis | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Meningitis | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Pneumocystis | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Recurrent bacterial pneumonia | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.2 |

| CMV infection | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Other fungal infections (histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis etc.) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Total | 521 | 100 | ||

3.4. Multivariate Analysis Results

Our multivariate analyses confirmed the results found in our univariate analyses of the associations between OI occurrence and sex, age, and CD4 count below 200 copies/mm3. The male gender (p=0.001) and age greater than 50 years (p=0.01) were found to be significantly associated to developing and having and OI. Subjects with CD4 count less than 200 copies/mm3 were three times more susceptible to developing OIs. On the other hand, there was no association between the type of antiretroviral regimen and the onset of OI (Table 8).

| Variables | Opportunistic infections | n | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YES (n%) | NO (n%) | |||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 273 (27.7) | 879 (76.3) | 1152 | Ref | ||

| Male | 146 (31.4) | 319 (68.6) | 465 | 1.47 | 1.16-1.87 | 0.001 |

| Age (in years) | ||||||

| 20-29 | 28 (16) | 147 (84) | 175 | Ref | ||

| 30-39 | 137 (22.8) | 464 (77.2) | 601 | 0.65 | 0.41-1.01 | 0.050 |

| 40-49 | 147 (29) | 360 (71) | 507 | 0.62 | 0.50-0.78 | 0.000 |

| ≥50 | 107 (32) | 227 (68) | 334 | 2.57 | 2.44-2.71 | 0.010 |

| Level of Education | ||||||

| No formal education | 15 (11.9) | 39 (12.6) | 54 | Ref | ||

| Primary | 111 (88.1) | 270 (87.4) | 381 | 0.94 | 0.92-1.07 | 0.830 |

| Secondary | 229 (93.3) | 693 (94.7) | 922 | 1.16 | 0.63-2.15 | 0.627 |

| University | 64 (81) | 196 (83.4) | 260 | 1.18 | 0.61-2.28 | 0.626 |

| CD4 on initiation | ||||||

| ≥350 | 56 (16.8) | 278 (83.2) | 334 | Ref | ||

| 0-199 | 246 (38.6) | 392 (61.4) | 638 | 3.12 | 2.24-4.33 | 0.000 |

| 200-349 | 104 (22.1) | 366 (77.1) | 470 | 2.21 | 1.69-2.89 | 0.000 |

| ARV treatment | ||||||

| 1=TDF/3TC/EFV | 330 (27.2) | 885 (72.8) | 1215 | Ref | ||

| 2=TDF/3TC/NVP | 41 (20.4) | 160 (79.6) | 201 | 0.70 | 0.49-1.01 | 0.050 |

| 3=AZT/3TC/NVP | 22 (17.7) | 102 (82.3) | 124 | 0.60 | 0.37-0.96 | 0.030 |

| 4=AZT/3TC/EFV | 07 (33.3) | 14 (66.7) | 21 | 1.44 | 0.58-3.58 | 0.435 |

| 5=AZT/3TC/LPV/r | 3 (60) | 2 (40) | 5 | 4.31 | 0.72-25.90 | 0.113 |

| 6=AZT/3TC/ATV/r | 4 (25) | 12 (75) | 16 | 0.95 | 0.31-2.97 | 0.933 |

| 7=TDF/3TC/LPV/r | 4 (80) | 1 (20) | 5 | 11.54 | 1.29-103.52 | 0.006 |

| 8=TDF/3TC/ATV/r | 4 (21.1) | 15 (78.9) | 19 | 0.76 | 0.25-2.30 | 0.627 |

| 9=ABC/3TC/LPV/r | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 2 | 2.86 | 0.18-45.89 | 0.436 |

| 10=ABC/3TC/ATV/r | 3 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) | 8 | 1.72 | 0.41-7.23 | 0.453 |

4. Discussion

Although HIV is the initial causative agent of AIDS, the majority of the morbidity and mortality cases observed in immunocompromised patients result from OI due to decreased immune defenses. The objective of our study was to describe the epidemiological profile of OI in HIV-infected patients managed in accredited treatment centers (ACTs) and care/treatment units (UPEC) in the cities of Yaoundé and Douala, Cameroon.

In our study, we observed that over three quarter of those infected with HIV were women, which is consistent with the 2011 DHS data.12. This predominance could be explained by the natural anatomical and physiological predispositions that make women more vulnerable to HIV infection. Moreover, these results are similar to the 60% obtained by a study in Ethiopia in 201313 and to 68.8% in Togo in 2011.14 The mean age in our study was 41.27 ± 10.17 years old. This result is similar to mean age of 41 years old recorded in Dakar.15 The most represented age group was 30-39 years old. This could be explained by the high sexual activity in this age group and it similarly to the 35-39 years age-group obtained in Cameroon.16 More than half of the patients had at least a secondary education level. This result is similar to that obtained by another study in Cameroon, where 47.8% of patients had secondary education.17 Majority of the participants were single. This is consistent with the results in another study in Cameroon.17 However, these results differ from those found in India,18 as well as in Dakar, Senegal,19 where married women make up 86% and 40% of the study population. These differences could be explained by the fact that in Dakar, Senegal, the population is mostly Muslim whereas in our study, the population mostly Christian. Early marriage and polygamy is more common among Muslim population than among Christians.

More than half of the patients “discovered” their status as a result of clinical suspicion. This could be due to the fact that our study population were patients diagnosed during the “opt-in” era when HIV testing was not proposed systematically to patients. Therefore, clinicians mostly proposed HIV testing to clients when they had a clinical suspicion, leading to many people being diagnosed when they present with clinical signs and symptoms. This result corroborates that of another study in the United States, where 52% of patients had clinical signs and symptoms recognized as diagnostic grounds for HIV testing.20

HIV1 was our most represented strain just as in prior studies.21, 22 More than half of our participants had at least one symptom of HIV infection. This result is lower than that obtained in Republic of Benin, where 96.3% of patients infected with HIV were symptomatic.23 This difference could be related to the fact that in the study conducted in Benin was among patients who presented for consultation, which considerably increased their result.

The majority of our participants had a CD4 + T cell count <200copies/mm3 which is similar to the results obtained in the United States.20 This implies that these participants are at risk of developing an advanced disease based on the WHO definition for advanced HIV disease. This finding, however, differs from that obtained in Benin, 68.8%24 and in Togo 73.8%.14 The differences may be due to the fact that these studies were done in 2004 and 2011, respectively, when the HIV/AIDS treatment initiation rates were even lower. Very few of our participants had viral load results available in their medical records. This could be explained by the fact that in 2014, viral load assay were not very accessible and were only requested when there was an immunological failure. The average viral load result was 293,558 copies/mm3. This value is close to what was obtained in a study on the evaluation of ART in a clinic in Rio de Janiero, Brazil,25 and implies that the majority of these patients are at risk of developing an OI. The most recent average TCD4 lymphocyte count was 412 copies/mm3. This result corroborates that of Dokekias et al. in Congo, who after 24 months of treatment, achieved an average TCD4 lymphocyte count of 353 copies/mm326. More than half of the patients were on first-line antiretroviral therapy. This is comparable to the results published in the 2016 Cameroon National AIDS Control Committee (NACC) report.

4.1. Limitations of the study

Like any retrospective study, this study suffers from an information bias as some patients’ clinical information and laboratory investigations results may have been lost due to poor achieving.

5. Conclusion and Global Health Implications

This study was conducted with the objective of describing the epidemiological profile of OIs in patients on treatment in accredited HIV treatment centers and care units in the cities of Yaoundé and Douala. OIs were found to be more common among people within the age group of 40 years and above and the majority were females. More than half of the patients had a CD4 count of less than 200copies/mm3 at baseline and the majority of patients were classified as WHO clinical stage III. Almost all the patients (95.4%) were on first-line ARV treatment. The prevalence of OI in HIV infected patients in the cities of Yaoundé and Douala was 25.9%. Factors associated with the occurrence of opportunistic infection were: gender (males), age (≥ 50 years), and CD4 count (<200/mm3). These findings have implications in that there is need to place emphasis on and take implement measures to improve regular immunologic monitoring (by use of CD4 assessment) as a means to identify HIV infected patients at risk of developing OIs and hence reduce excessive dependence on clinical signs and symptoms as is the practice especially in developing countries. Finally, our findings suggest that public health interventions for reducing HIV related co-morbidities (and implicitly mortality) should especially target the male gender for greater impact in addition to other measures.

Acknowledgements:

The authors are grateful to the following hospitals in Douala and Yaounde for allowing us have access to their data: Yaoundé Central Hospital, Yaoundé General Hospital, Yaounde National Social Insurance Fund Hospital (La Caisse), Yaoundé Police Hospital, Efoulan District Hospital, Bastos Clinic, Yaoundé, Nylon District Hospital,Bonassama District Hospital, Cité des Palmiers District Hospital, Logbaba District Hospital, Mboppi Baptist Hospital, and Bonamoussadi “AD LUCEM” Hospital.

Competing Interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Funding: There was no funding for this study.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the National Ethics Committee (reference N° 2017/345/CNEC/DR/MSP). Administrative clearance was obtained from the hospital authorities and the head of service of HIV/AIDS Care and Treatment Center. Patient consent was waived for the study because it was a non-interventional study involving retrospective review of records only. However, confidentiality was respected in treating patients’ records. No data that could make identification of patients was collected.

References

- Origins of HIV and the AIDS Pandemic. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 2011;1(1) doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a006841

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation of a T-lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) Science. 1983;220(4599):868-871. doi:10.1126/science.6189183

- [Google Scholar]

- A Pathogenic Retrovirus (HTLV-III) Linked to AIDS. New England Journal of Medicine. 1984;311(20):1292-1297. doi:10.1056/nejm198411153112006

- [Google Scholar]

- Questions-réponses sur la syphilis. Arcat 2019 https://www.arcat-sante.org/a/publi/docs/question

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent Insights into the HIV/AIDS Pandemic. Microbial Cell. 2016;3(9):450-474. doi:10.15698/mic2016.09.529

- [Google Scholar]

- Review of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1–Related Opportunistic Infections in Sub-Saharan Africa. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2003;36(5):652-662. doi:10.1086/3676550

- [Google Scholar]

- Time to HAART Initiation after Diagnosis and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Patients with AIDS in Latin America. Plos One. 2016;11(6) doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0153921.8

- [Google Scholar]

- Manifestations Cliniques Observées au Cours de Linfection VIH. VIH et sida. ;2008:27-61. doi:10.1016/b978-2-294-70230-3.50004-2

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and Predictors of Opportunistic Infections Among HIV Positive Adults On Antiretroviral Therapy (On-ART) Versus Pre-ART In Addis Ababa, Ethiopia:A Comparative Cross-Sectional Study. HIV/AIDS - Research and Palliative Care. 2019;11:229-237. doi:10.2147/hiv.s218213

- [Google Scholar]

- 2019. Cameroon DHS, 2011 - Final Report (French). Cameroon:DHS, 2011 - Final Report (French). https://www.dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-FR260-DHS-Final-Reports.cfm

- 2019. Bulletin Epidémiologique. http://www.cnls.cm/sites/default/files/bulletin_epidemiologique_vih_ndeg5.pdf

- Infections opportunistes du VIH/sida chez les adultes en milieu hospitalier au Togo. Bulletin de la Sociétéde pathologie exotique. 2011;104(5):352-354. doi:10.1007/s13149-011-0139-3

- [Google Scholar]

- 2019. Cameroon DHS, 2011 - Final Report (French). Cameroon:DHS, 2011 - Final Report (French). https://www.dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-FR260-DHS-Final-Reports.cfm

- Profil biologique des patients adultes infectés par le VIH àl'initiation du traitement antirétroviral au Togo. Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses. 2011;41(5):229-234. doi:10.1016/j.medmal.2010.11.007

- [Google Scholar]

- Profil actuel des patients infectés par le VIH hospitalisés àDakar (Sénégal) Bulletin de la Sociétéde pathologie exotique. 2011;104(5):366-370. doi:10.1007/s13149-011-0178-9

- [Google Scholar]

- Distribution épidémiologique de l'infection àVIH chez les femmes enceintes dans les dix régions du Cameroun et implications stratégiques pour les programmes de prévention. Pan African Medical Journal. 2015;20 doi:10.11604/pamj.2015.20.79.4216

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and epidemiologic trends in HIV/AIDS patients in a hospital setting of Yaounde, Cameroon:a 6-year perspective. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2002;6(2):134-138. doi:10.1016/s1201-9712(02)90075-5

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of Opportunistic Infections and Its Correlation With CD4 T-Lymphocyte Counts and Plasma Viral Load Among HIV-Positive Patients at a Tertiary Care Hospital in India. Journal of the International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care. 2009;8(6):333-337. doi:10.1177/1545109709346881

- [Google Scholar]

- Dépistage tardif de l'infection àVIH àla clinique des maladies infectieuses de Fann, Dakar:circonstances de diagnostic, itinéraire thérapeutique des patients et facteurs déterminants. Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses. 2009;39(2):95-100. doi:10.1016/j.medmal.2008.09.021.20

- [Google Scholar]

- Review of Medical Encounters in the 5 Years Before a Diagnosis of HIV-1 Infection:Implications for Early Detection. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2003;32(2):143-152. doi:10.1097/00126334-200302010-00005.21

- [Google Scholar]

- Time to initiation of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients diagnosed with an opportunistic disease:a cohort study. HIV Medicine. 2014;16(4):219-229. doi:10.1111/hiv.12201.22

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic sérologique des infections àVIH. 2019. Développement et Santé. https://devsante.org/articles/diagnostic-serologique-des-infections-a-vih

- [Google Scholar]

- Profil clinique et immunologique des patients infectés par le VIH dépistés àCotonou, Bénin. Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses. 2004;34(5):225-228. doi:10.1016/j.medmal.2004.02.007

- [Google Scholar]

- Facteurs associés àla dissociation immunovirologique chez les patients infectés par le VIH-1 sous traitement antirétroviral hautement actif au Centre de Traitement Ambulatoire (CTA) de Dakar. Pan African Medical Journal. 2017;27 doi:10.11604/pamj.2017.27.16.98111

- [Google Scholar]

- An evaluation of antiretroviral HIV/AIDS treatment in a Rio de Janeiro public clinic. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2003;8(5):378-385. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01046.x

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected adults in the Department of Haematology, University Hospital of Brazzavllle, Congo. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1990. 2008;101(2):109-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Magnitude of opportunistic infections and associated factors in HIV-infected adults on antiretroviral therapy in eastern Ethiopia. HIV/AIDS - Research and Palliative Care. 2015;137 doi:10.2147/hiv.s79545

- [Google Scholar]