Translate this page into:

Exclusive Breastfeeding Rates and Factors Associated with Exclusive Breastfeeding Practices in Northern Tanzania: Measurement using Two Different Methodologies—24 Hours Recall and Recall Since Birth

*Corresponding author email: linnabenny@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background:

Exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) has many benefits to the child from mental to physical growth and development; however, methods of measuring EBF have raised a number of policy and programmatic questions. This study assesses EBF rates and factors associated with EBF practices in Northern Tanzania using two different methodologies, namely, the 24-hours recall and recall-since-birth.

Methods:

A cohort study was conducted from October 2013 to December 2015 among mother-infants’ pairs. Mothers with child delivery information (N=430) were followed and included in the analyses. We enrolled pregnant women who were in their third trimesters and interviewed them with the help of questionnaires at enrollment, delivery, 7 days and thereafter monthly up to nine months after delivery. At each visit after delivery, information on breastfeeding using the two methods (24 hours recall and recall-since-birth) was collected.

Results:

The prevalence of EBF dropped from one month to six months when using both the 24 hours recall and the recall since birth methods, but at different rates. At six months, 24.2% of the mothers practiced EBF when measured with the recall since birth method, compared to 38.8% when measured with the 24 hour recall. Predictors of EBF were also different. When using the recall since birth method, women who had received counseling on infant feeding had increased odds of practicing EBF compared to those who did not receive counseling, [AOR=2.3; 95% CI (1.2, 3.7)]. When using 24 hours recall, women who were unemployed had increased odds of practicing EBF compared to those who were employed [AOR=1.5;95% CI(1.1,2.5)], and women aged 35 - 49 years had decreased odds of practicing EBF compared to younger women[AOR=0.28; 95 % CI(0.1,0.7)].

Conclusions and Global Health Implications:

The two methods for EBF give substantially different results, both in the prevalence of EBF and factors associated with EBF. The higher EBF obtained with 24 hours recall represents an overestimation and thereby an overly positive picture of the situation.

Keywords

Breastfeeding

Exclusive Breastfeeding

Factors

Rates

24 Hours

Recall Since Birth

Tanzania

1. Introduction

Exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) has been reported to be the best way of feeding infants from birth to 6 months of age.1 EBF has been defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as giving only breast milk to the infant, without mixing it with water, other liquids, herbal preparations or food, with the exception of vitamins, mineral supplements or medicines.1,2 Exclusively breastfed infants have been shown to have lower rates of respiratory tract infections and diarrhea, better physical growth, neuro-developmental outcomes and in some countries higher intelligent quotient compared to infants who were not exclusively breastfed.3–5 Despite the benefits of EBF, this practice is still low compared to the WHO recommendations that at least 90 % of all infants less than 6 months should be exclusively breastfed6. It is currently estimated that only 40 % of infants less than six months are exclusively breastfed globally and 39 % in developing countries.7

The prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding has been improving over the years. However, there may be large variations from country to country or within a country. Studies from Ethiopia have shown a variation in EBF prevalence from 36 % in Northwest Ethiopia to 82 % in Oromia region.8–12 In Tanzania different studies have reported EBF prevalence ranging from 20 % in Kilimanjaro region, 25 % in Tanga region to 58 % in Kigoma.13–15 Using information from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), the prevalence of EBF in Tanzania has been improving over the years from 26 % in 1991-92, 41% in 2004-05, 50 % in 2010 and 59 % in 2015-2016.16

The method that has been used in many studies to present prevalence of EBF has been 24 hours recall. Many questions have been raised regarding this method and its ability to provide clear figures to present prevalence of EBF. A paper by Greiner discussed this issue in detail and showed that the method which has been used over the years has been exaggerating the actual EBF rates. This has been supported by other studies comparing data from 24 hours recall with recall since birth when calculating prevalence of EBF. In Eastern Uganda, for example, Engerbresten et al. showed the EBF prevalence at 1, 3 and 6 months to be 96 %, 81 % and 52 % when using 24 hours recall method compared to 45 %, 7 % and 0 % respectively when using recall since birth.17 However, Agampondi et al. reported that all retrospective evaluation methods overestimate the duration of EBF, whether using mothers recall (77.7 %) or calendar month (41 %) compared to prospective cohort design (23.9 %)18. There is thus contrasting information regarding the best method to measure EBF rates.17,18

Different studies have reported factors that influence the practice of EBF. The factors include that maternal age, education status, employment status, marital status, HIV status, place of delivery, and knowledge on breastfeeding, counselling on breastfeeding, antenatal care attendance and type of delivery.13,15,19–21 None of the previous studies have assessed if using different methods makes a difference when assessing factors associated with EBF within the same population. Given that there is a discussion on which method is better for measuring EBF rates there is a need for more knowledge concerning the choice of method when assessing predictors of EBF.

This study presents data from a cohort study where women were enrolled during third trimester of pregnancy in Moshi urban, Tanzania, and followed at delivery, 7 days and thereafter monthly up to nine months after delivery, and at each visit, information on breastfeeding using the two methods: 24 hours recall and recall-since-birth was collected.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study design and subjects

This was a cohort study that enrolled women in their third trimester of pregnancy. The study was conducted between October 2013 to December 2015. The study was conducted in the two largest government primary health care (PHC) clinics, Majengo and Pasua located at Moshi urban district in Kilimanjaro, a region in the northern part of Tanzania. Moshi urban is the capital of the region, and one of the seven districts in the region. The region has a total population of 1,640,087 people with approximately 184,292 people living in Moshi municipality.22 The district has approximately a total of 11,600 deliveries per year. Of the total deliveries per year, 11% are from Majengo Health center and 7% from Pasua health center.23

Reproductive health care clinics are well attended in the district, with antenatal coverage of 100 %, skilled birth attendance coverage of 100 %, and 97 % of children are fully immunized, compared to the national level of 98 %, 64 %, and 75 % respectively.16 Because of the high coverage in this area, the population of children aged 0 - 6 months seen at health facilities, can be representative to the general population.

2.2 Enrolment and follow up procedures

Women who were attending antenatal care at the two clinics were first informed about the study, its aims and follow up requirement. The two clinics serve a population of approximately 1,150 pregnant women. In this study a total of 536 pregnant women in their 3rd trimester, who were residing in Moshi urban district were approached and all agreed to participate in the study. After agreeing they gave a written consent to participate in the study and were recruited from October 2013 to April 2014. More details of the recruitment process are written elsewhere.24 All 536 women who were approached agreed to participate and completed the first interview. After the interview all women were reminded that they will be followed at delivery, seven days after delivery, at one month after delivery thereafter monthly up to nine months.

2.3. Breastfeeding cohort information

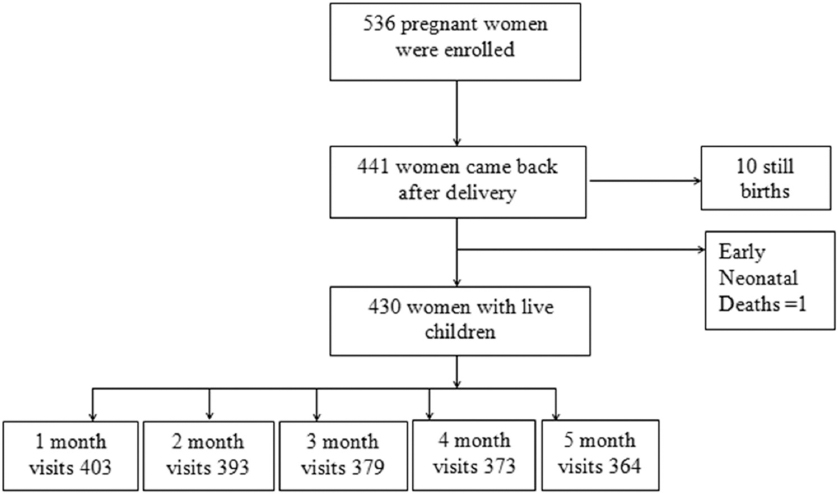

This paper is based on data from mother-infants pairs collected from delivery up to six months. Figure 1 depicts a flow chart for participants. Out of the 536 enrolled women, we had delivery information on 441 and 95 were lost to follow up. A total of 430 women formed a cohort for analyzing exclusive breastfeeding rates using the recall since birth and 24 hours recall and 364 women completed all the interviews up to 6 months.

- Flow chart of the study participants

The reasons for loss of follow up were; women moved from one location to another without giving notice and giving wrong contact information. At enrollment, women were requested to give cell/mobile telephone numbers so as to contact them in case they miss the scheduled follow up. For women who missed the follow up, when we called the cell numbers, some were not in service and some belonged to their relatives/husbands. The relatives were given message to deliver to them which we are not sure if it was delivered. Of the 441 women with delivery information, 10 had still birth and one neonatal death which occurred 10 days after delivery (Figure 1).

2.4. Questionnaires

The women who agreed to participate were interviewed in private, using a questionnaire, and the local language Swahili, was used in all the interviews. Four different questionnaires were used, one at enrolment, one at delivery, one at seven days after delivery and one for the interviews at each month after delivery. The questionnaires were pretested at a different facility which was not included in the study. The pre-testing aimed at orienting the research team to the tools and making any corrections if the questions were not clear.

At enrolment, the questionnaire included socio-demographic data of the women and their partners (age, education, income, marital status, employment, and alcohol intake), maternal reproductive health information and knowledge on Infant feeding and counseling on breastfeeding.

The questionnaire at delivery included the following information: maternal characteristics (type of delivery, assistance during delivery, place of delivery), child information (birth weight, sex, pre term; initiation on breastfeeding, colostrum giving and pre lacteal feeds). The questionnaire at seven days visit included information on exclusive breastfeeding; any breastfeeding problem (mastitis, engorgement, cracked nipple) was collected. The questionnaire at each monthly visit included information whether the mother is still breastfeeding, if she has introduced water, semi solid foods and any other solid foods.

To assess the practice of EBF, we used two methods at each visits. First was 24 hours recall method whereby a mother was asked to list all the foods/liquids/semisolids foods that were given to the child apart from breast milk for the past 24 hours. Second recall since birth methods was used assess EBF practice at each monthly visit. A mother was asked the type of drinks (water or nutritious drinks), food and time when she introduced to the child since the child was born.

2.5. Data processing and analysis

Data were entered and analyzed using SPSS version 20 (SSPS, Chicago, IL, USA). In this paper, the analysis was based on 430 women who had complete delivery information and a live baby (Figure 1). Continuous data were summarized by using mean (standard deviation) while proportions were used to summarize categorical variables. Differences between groups were assessed using Chi square test. Prevalence of EBF was obtained monthly with two different methods: 24 hours recall and recall since birth. For recall since birth, a mother was categorized to have practiced EBF if she has not given water, liquids, semisolids or solid food. For 24 hours recall, a mother was considered to have practiced EBF if she has not given her infant water, liquids, semisolids or solid food for the past 24 hours. Odds ratio (OR) with their associated 95% confidence intervals were used to assess the strength of association between exclusive breastfeeding and predictor variables when using the two methods. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to control for confounders.

2.5.1. Ethical Consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from Ethical committee of Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College (Ethical Clearance certificate number 899) and permission to conduct the study at Municipal facilities was sought from District Medical officer of Moshi municipal and Heads of Majengo and Pasua health committees. Also ethical clearance was obtained from the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics, Norway (2016/109/REK sør-øst)). A written informed consent was sought from each participant before the enrolment and for those who could not write a right thumb print was used. Research subjects were identified only by a code number in all the questionnaires.

3. Results

Comparison of women who came back even once (n=441) and those who did not come back at all after delivery (n=95) is presented in Table 1. The younger mothers (15-24 years) were significantly less likely to come back for follow up than the older women (p=0.01) and women who had one pregnancy were significantly less likely to come back than the others (p=0.004).

| Characteristics | Attended follow up visits | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes n (%) | No n (%) | ||

| Mother’s | |||

| Age (years) | |||

| 15-24 | 198 (45.5) | 60 (62.5) | |

| 25-34 | 198 (45.5) | 29 (30.2) | 0.01 |

| 35-49 | 39 (9.0) | 7 (7.3) | |

| Education | |||

| No formal education | 8 (1.8) | 5 (5.2) | |

| Primary education | 261 (60.0) | 59 (61.5) | 0.12 |

| Secondary and higher | 166 (38.2) | 32 (33.3) | |

| Employment | |||

| Employed | 304 (69.9) | 58 (60.4) | |

| Not employed | 131 (30.1) | 38 (39.6) | 0.07 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/cohabiting | 389 (89.4) | 85 (88.5) | |

| Single/separated/divorced/widowed | 46 (10.6) | 11 (11.5) | 0.8 |

| Parity | |||

| Once | 142 (50.7) | 22 (51.2) | |

| 2-3 times | 128 (45.7) | 19 (44.2) | 0.98 |

| 4-5 times | 10 (3.6) | 2 (4.7) | |

| Gravida | |||

| 1 pregnancy | 140 (32.2) | 48 (50.0) | |

| 2-3 pregnancy | 233 (53.6) | 40 (41.7) | 0.004 |

| >4 pregnancy | 62 (14.3) | 8 (8.3) | |

| HIV status of the woman | |||

| Positive | 26 (6.0) | 7 (7.4) | |

| Negative | 409 (94.0) | 88 (92.6) | 0.61 |

| Antenatal visits | |||

| Once | 15 (3.5) | 1 (1.0) | |

| 2-3 times | 274 (64.6) | 67 (69.8) | 0.3 |

| 4 and above | 135 (31.8) | 28 (29.2) | |

Table 2 shows the delivery information of the 431 women who came back after delivery at least once and had live birth. Most babies were born with weight above 2500gm (96.6 %). Most women delivered at a health facility (99 %). Ninety nine percent of women choose exclusive breastfeeding as their infant feeding option and 85 % and 95 % were able to initiate breastfeeding within the first hour after delivery and give colostrum respectively.

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Place of delivery (n=418) | ||

| Health facility | 414 | 99.0 |

| Home | 4 | 1.0 |

| Type of delivery (n=428) | ||

| Spontaneous vaginal delivery | 395 | 92.3 |

| Caesarian section | 33 | 7.7 |

| Birth weight (n=414) | ||

| >2500 gm | 400 | 96.6 |

| <2500 gm | 14 | 3.4 |

| Infant feeding option chosen (n=417) | ||

| EBF | 414 | 99.3 |

| Cow milk | 2 | 0.5 |

| Infant formula | 1 | 0.2 |

| Breastfeeding initiation (n=403) | ||

| Within 1hour after delivery | 343 | 85.2 |

| After 1hour but within 24 hours | 30 | 7.4 |

| After 24 hours | 30 | 7.4 |

| Colostrum given (n=425) | ||

| Yes | 407 | 95.8 |

| No | 18 | 4.2 |

Table 3 presents the prevalence of EBF for each month using the two methods. There is a difference between the methods; 24 hours recall shows a higher prevalence rate than recall since birth throughout the six months. Predictors of EBF using recall since birth and 24 hours recall method are shown in Tables 4 and 5. A bivariate logistic regression using recall since birth method shows that women who have received counselling on infant feeding have increased odds [COR =2.1; 95 % CI (1.2, 3.5)] of practicing EBF compared to those who did not receive counseling (Table 4). In multivariate analysis, these results remained significant when adjusting for knowledge on EBF definition and appropriate breastfeeding knowledge [AOR=2.3; 95 % CI (1.2, 3.7)] (see Table 4).

| Variables | Recall since birth | 24 hours recall |

|---|---|---|

| 1 month EBF (n=403) | 387 (96.0) | 403 (100.0) |

| 2 month EBF (n=393) | 344 (87.5) | 372 (94.7) |

| 3 month EBF (n=379) | 282 (74.4) | 334 (88.1) |

| 4 month EBF (n=373) | 213 (57.1) | 280 (75.1) |

| 5 month EBF (n=363) | 87 (24.2) | 141 (38.8) |

| Variables | N | EBF up to 6month n(%) | OR 95%CI | AOR 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| 14-24 | 169 | 35 (20.7) | 1 | - |

| 25-34 | 161 | 43 (27.0) | 1.4 (0.8, 2.3) | |

| 35-49 | 32 | 9 (28.1) | 1.4 (0.6, 3.5) | |

| Education | ||||

| No formal education | 6 | 3 (50.0) | 1 | - |

| Primary education | 224 | 52 (23.4) | 0.3 (0.1, 1.5) | - |

| Secondary and higher education | 23 | 32 (24.2) | 0.3 (0.1 , 1.6) | - |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/cohabiting | 323 | 82 (25.4) | 1 | - |

| Single/separated/divorced | 37 | 5 (13.5) | 0.4 (0.1 , 1.2) | |

| Polygamy | ||||

| No | 284 | 72 (25.4) | 1 | |

| Yes | 36 | 7 (19.6) | 0.7 (0.2 , 1.6) | |

| Don’t Know | 10 | 3 (30.3) | 1.2 (0.3,5.0) | |

| Employment | ||||

| Yes | 253 | 61 (24.1) | 1 | |

| No | 107 | 26 (24.3) | 0.9 (0.5 , 1.6) | |

| Number of pregnancies | ||||

| 1st pregnancy | 118 | 24 (20.3) | 1 | - |

| 2-3 pregnancies | 189 | 54 (28.6) | 1.5 (0.9 , 2.7) | |

| 4 and above | 54 | 9 (17.0) | 0.8 (0.3 , 1.8) | |

| Parity | ||||

| Once | 115 | 33 (28.7) | 1 | |

| 2-3 times | 106 | 28 (26.4) | 0.8 (0.4 , 1.6) | |

| 4 and above | 8 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0 ,-) | |

| Antenatal visits | ||||

| Once | 14 | 3 (21.4) | 1 | - |

| 2-3 times | 227 | 47 (20.7) | 0.9 (0.2 , 3.5) | |

| 4 and above | 111 | 35 (31.5) | 1.6 (0.4 , 6.4) | |

| Counselling on appropriate breastfeeding practices | ||||

| Yes | 181 | 56 (30.9) | 2.1 (1.2 , 3.5) | 2.3 (1.2 , 3.7) |

| No | 179 | 31 (17.3) | 1 | 1 |

| Appropriate breastfeeding knowledge | ||||

| Yes | 107 | 23 (21.5) | 0.8 (0.4 , 1.4) | 0.8 (0.4,1.4) |

| No | 253 | 64 (25.3) | 1 | |

| Knowledge on exclusive breastfeeding definition | ||||

| Correct definition | 298 | 73 (24.5) | 1 | |

| Incorrect definition | 61 | 14 (23.0) | 0.9 (0.4 ,1.7) | 0.9 (0.4,1.7) |

| Age of last born | ||||

| <2 years | 25 | 6 (24.0) | 1 | - |

| 2-4 years | 80 | 16 (20.0) | 0.7 (0.2 , 2.3) | - |

| >4 years | 110 | 35 (31.8) | 1.4 (0.5 , 4.0) | - |

In bivariate logistic regression using 24 hours recall, women who were unemployed had increased odds of practicing EBF compared to those who were employed [COR=1.5; 95 % CI (1.1, 2.5)]. Furthermore, women aged 35 - 49 years had decreased odds of practicing EBF [COR=0.28; 95% CI (0.1, 0.7)] than women of younger age and these associations remained significant after adjusting for all other factors in the model (see Table 5).

| Variables | N | EBF up to 6month 24hrs recall n (%) | OR 95%CI | AOR 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| 14-24 | 169 | 70 (41.4) | 1 | |

| 25-34 | 159 | 64 (40.3) | 0.9 (0.6 , 1.4) | |

| 35-49 | 32 | 7 (21.9) | 0.3 (0.1 , 0.9) | 0.3 (0.1 , 0.9) |

| Education | ||||

| No formal education | 6 | 4 (66.7) | 1 | - |

| Primary education | 222 | 85 (38.3) | 0.3 (0.1 , 1.7) | - |

| Secondary and higher education | 132 | 52 (39.4) | 0.3 (0.1 , 1.8) | - |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/cohabiting | 323 | 129 (39.9) | 1 | - |

| Single/separated/divorced | 37 | 12 (32.4) | 0.7 (0.3 , 1.4) | |

| Polygamy* | ||||

| No | 284 | 114 (40.1) | 1 | |

| Yes | 36 | 10 (27.8) | 0.5 (0.2 , 1.2) | |

| Don’t know | 10 | 5 (50.0) | 1.4 (0.4 , 5.2) | |

| Employment | ||||

| Yes | 253 | 108 (42.7) | 1 | |

| No | 107 | 33 (30.8) | 1.6 (1.0, 2.7) | 1.5 (1.1 ,2.5) |

| Number of pregnancies | ||||

| 1st pregnancy | 118 | 49 (41.5) | 1 | - |

| 2-3 pregnancies | 189 | 71 (37.6) | 0.8 (0.5 , 1.3) | |

| 4 and above | 53 | 21 (39.6) | 0.9 (0.5 , 1.8) | |

| Parity* | ||||

| Once | 115 | 44 (38.3) | 1 | |

| 2-3 times | 106 | 43 (40.6) | 1.1 (0.6 , 1.8) | |

| 4 and above | 8 | 1 (12.5) | 0.2 (0.03 , 1.9) | |

| Antenatal visits* | ||||

| Once | 14 | 6 (42.9) | 1 | - |

| 2-3 times | 227 | 93 (41.0) | 0.9 (0.3 , 2.7) | |

| 4 and above | 111 | 40 (36.0) | 0.7 (0.2 , 2.3) | |

| Counselling on appropriate breastfeeding practices | ||||

| Yes | 181 | 69 (38.1) | 0.9 (0.6 , 1.4) | |

| No | 179 | 72 (40.2) | 1 | - |

| Appropriate breastfeeding knowledge | ||||

| Yes | 173 | 32 (18.5) | 0.8 (0.5 , 1.2) | |

| No | 358 | 80 (22.3) | 1 | |

| Knowledge on exclusive breastfeeding | ||||

| Correct definition | 298 | 116 (38.9) | 1 | |

| Incorrect definition | 61 | 25 (41.0) | 1.1 (0.6 , 1.9) | |

| Age of last born* | ||||

| <2 years | 25 | 9 (36.0.1) | 1 | - |

| 2-4 years | 80 | 29 (36.3) | 1.0 (0.3 , 2.6) | - |

| >4 years | 110 | 45 (40.9) | 1.2 (0.5 , 3.0) | - |

4. Discussion

In this study, it was found that exclusive breastfeeding rates decline before the children reach six months when using both the recall since birth method and 24 hours recall. However, prevalence and factors associated with EBF were different when using the two methods. Counseling had a positive effect on practicing EBF when using the recall since birth method, whereas employment and maternal age had a significant effect when using 24 hours recall.

The results showed that EBF rates were consistently lower when using the recall since birth method than when using 24 hours recall method. At 1, 3 and 6 months, the EBF rates were 96%, 74.4% and 24 % respectively, when using recall since birth and 100%, 88% and 39% respectively, when using 24 hours recall.

These differences are slightly less than what was found in a study from Eastern Uganda where EBF rates at 1, 3 and 6 months were 45 %, 7 % and 0 % when using the recall since birth method compared to 96 %, 81 % and 52 % when using 24 hours recall.25 Other studies conducted in Ethiopia and Mansoura reported significant differences in EBF rates using the recall since birth and 24 hours recall showing that the 24 hours methods overestimated the EBF rates.26,27 The results from these studies and our study indicate the importance of using both methods in estimating EBF rates. There may be many explanations to the differences in EBF rates when using the two methods. When using the 24 hours recall method the mother only has to recall for the past 24 hours and if the child was not given anything apart from breast milk in that time period, this mother will be classified as practicing EBF. This is regardless of whether the child is given water, other liquids, herbal preparations or food on other days. Thus this method is likely to overestimate the rates of EBF. The recall since birth methods as used in the preset study went more into detail on breastfeeding and introduction of foods and drinks and questions were repeated monthly. The moment a mother started to introduce any other food or drink apart from breast milk it was considered as the discontinuation of EBF. This way of measuring EBF by recalling all the breastfeeding practices since birth, seems to be more in line with WHO definition of EBF.

A standard method for assessing exclusive breastfeeding, used in the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), is 24 hours recall at 6 months. DHS data present point prevalence from 0 - 6 months, where mothers were asked about breastfeeding practices in the past 24 hours preceding the survey.28 There are many considerations behind the choice of methods connected to the aim of the study and available resources. It should be kept in mind that the choice of the method will have relevance for the results and potential for appropriate action. In cases where the EBF rates are substantially overestimated, this might not trigger the effort to be taken to improve the situation. Thus, there is a need to rethink the best way to report matters that are important to health like EBF.

With regards to the area-specific issues around the study, there seems to be a slight improvement in EBF practices, when comparing the data from the present study with another study which was also done in Moshi, Tanzania. That study was based on cohort data collected in 2002 – 2006; EBF was measured using recall since birth at one, three and six months and the rates were 49%, 22% and 0.2% respectively.29 The improvement can be due to the counseling the mothers receive from health providers on the importance of EBF.

In the present study, those women who received counseling were more likely to practice EBF for 6 months than those who did not receive any counseling, as shown when using the recall since birth method. This has also been observed in studies from other countries, such as Nigeria, Egypt, and Ethiopia.11,30,31 This may be because every time women come for antenatal visits they receive information about infant feeding and the importance of EBF. It is important to continue giving antenatal counseling to all pregnant women that attend clinic since it has been shown to have benefits to the promotion on breastfeeding.

Women who were aged 35 to 49 years were found to be less likely to practice EBF compared to women of younger age when using 24 hours recall. This is different from other studies where mother’s age had a positive effect on EBF. A Canadian study indicated that women who gave birth at older age were more likely to practice EBF.32 This was also seen among Norwegian women in another study.19 In the present study, the negative effect might be because many women tend to use their own experience to a larger extent than what they have learned in the antenatal clinics. The older women have given birth many times; hence, it is possible that they are following whatever they were practicing before without taking into consideration the new messages that were taught in the clinic.

Women who are unemployed have increased odds or practicing EBF up to 6 months than women who are employed in the formal sector. This has also been seen in studies from three different parts of Ethiopia where unemployed women were more likely to practice EBF.10,11,33 This shows that policies about maternity leave need to be looked at so as to promote EBF for employed women. There is also a need to improve work place environment locations, such as infant nurseries, where women with infants can leave their children and come to breastfeed their infants without any problems.

4.1. Strength and limitations of the study

This study was able to use longitudinal data with rich information on infant feeding practices, which is unique. The study was able to collect data on breastfeeding and other dietary data of the child every month from one to six months.

However, a limitation of the dietary recall since birth is the potential recall bias, as the mothers might forget when they introduced a food item. Another limitation of this study was the dropout rates. To minimize dropout rates, reminders were given to the mothers about the follow up. Mothers at the risk of drop out due to inconvenient appointment dates were contacted through phone calls and an alternative date was given.

5. Conclusion and Global Health Implications

This study has shown that there is a difference in the prevalence of EBF when using the two methods: the 24 hours recall gave higher EBF rates than recall since birth. Measuring the duration of EBF is complicated, since factors like timing, recall bias and method of analysis can affect the outcome. Based on the results from this study, and considering the way the data were collected, it can be argued that the higher EBF obtained with 24 hours recall represents an overestimation and thereby an overly positive picture of the situation. The 24 hours recall method has been used in many studies due to the fact that it is cheap to conduct in large population groups. It is important to keep in mind that the type of method used can have implications for both prevalence and predictors of EBF. However, both methods have their strengths and limitations and may reveal important points. Based on data from the recall since birth method, this study indicated those mothers who have received counseling on infant feeding are more likely to practice EBF. Therefore, the authorities should ensure that all primary health care facilities are equipped to be able to deliver such counseling. The data from 24 hours recall indicated that mothers that are employed had more chances of feeding their infants exclusively up to six months; hence the employers should consider ways to enable employed women to exclusively breastfeed their infants by considering the introduction and or strengthening of paid maternity leave.

Acknowledgement

The study was funded by The Letten Foundation of Norway. We also thank the women of Kilimanjaro for participating in this study, and the Regional & District Medical Officers for permission to conduct the study.

Conflict of interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding: The funding for conducting this study was secured from The Letten Foundation of Norway.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by a relevant institutional review board or ethics committee.

References

- Community-Based Strategies for Breastfeeding Promotion and Support in Developing Countries. GENEVA: Department of Child and Adolescent Health and Development; 2003.

- Infant and Young Child Feeding:Model Chapter for Textbooks for Medical Students and Allied Health Professionals.; 2009. WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data; 2009. p. :3-6.

- Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet (London, England). 2013;382(9890):427-451. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X

- [Google Scholar]

- Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Cochrane database Syst Rev (8):CD003517. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003517.pub2

- [Google Scholar]

- A cluster randomised controlled trial of the community effectiveness of two interventions in rural Malawi to improve health care and to reduce maternal, newborn and infant mortality. Trials. 2010;17(11):88. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-11-882010:1-15

- [Google Scholar]

- Child survival II How many child deaths can we prevent this year ? Lancet. 2003;362:65-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Global trends in exclusive breastfeeding. Int Breastfeed J. 2012;7(1):1. doi:10.1186/1746-4358-7-12

- [Google Scholar]

- Breastfeeding practices and associated factors among female nurses and midwives at North Gondar Zone, Northwest Ethiopia:a cross-sectional institution based study. Int Breastfeed J. 2014;9(1):11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge and practice of mothers towards exclusive breastfeeding and its associated factors in Ambo Woreda West Shoa Zone Oromia region, Ethiopia. Epidemiology(sunnyvale). ;5:182. doi:10.4172/2161-1165.1000182

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding practices among mothers in Dubti Town, Afar regional state, Northeast Ethiopia:a community based cross-sectional study. Int Breastfeed J 2016:1-6. doi:10.1186/s13006-016-0064-y

- [Google Scholar]

- Exclusive breastfeeding and associated factors among mothers in Debre Markos, Northwest Ethiopia:a cross-sectional study. Int. Breasfeed J 2015:1-7. doi:10.1186/s13006-014-0027-0

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and predictors of exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life among women in Halaba Special Woreda, Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples'Region/SNNPR/Ethiopia :a community based cross-sectional study. Arch Public Heal 2015:1-11. doi:10.1186/s13690-015-0098-4

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors Affecting Exclusive Breastfeeding among Women in Muheza District Tanga Northeastern Tanzania:A Mixed Method Community Based Study. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(1):77-87. doi:10.1007/s10995-015-1805-z

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and predictors of exclusive breastfeeding among women in Kilimanjaro region, Northern Tanzania:A population based cross-sectional study. Int Breastfeed J. 2013;8(1) doi:10.1186/1746-4358-8-12

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and predictors of exclusive breastfeeding among women in Kigoma region, Western Tanzania:a community based cross- sectional study. Int Breastfeed J. 2011;6(1):17. doi:10.1186/1746-4358-6-17

- [Google Scholar]

- Tanzania Demographic Health Survey and Malaria Indicator Survey (TDHS-MIS). Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania, and Rockville, Maryland, (MoHCDGED) USA: MoHSW, MoH, NBS, OCGS and ICF International;

- Low adherence to exclusive breastfeeding in Eastern Uganda:a community-based cross-sectional study comparing dietary recall since birth with 24-hour recall. BMC Pediatr. 2007;7:10. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-7-10

- [Google Scholar]

- Duration of exclusive breastfeeding:validity of retrospective assessment at nine months of age. BMC Pediatr. 2011;14(11):80. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-11-80

- [Google Scholar]

- Infant feeding practices and associated factors in the first six months of life:the Norwegian infant nutrition survey. Acta Paediatr. 2003;92(2):152-161.

- [Google Scholar]

- Do Baby-Friendly Hospitals Influence Breastfeeding Duration on a National Level? Pediatrics. 2005;116(5):e702-708. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-0537

- [Google Scholar]

- Exclusive breast-feeding is rarely practised in rural and urban Morogoro, Tanzania. Public Health Nutr. 2001;4(2):147-154. doi:10.1079/PHN200057

- [Google Scholar]

- The United Republic of Tanzania Population Distribution by Age and Sex 2013

- Moshi Municipal Health Department Annual Report 2015

- Predictors of appropriate breastfeeding knowledge among pregnant women in Moshi Urban, Tanzania:A cross-sectional study. Int Breastfeed J. 2017;12(1) doi:10.1186/s13006-017-0102-4

- [Google Scholar]

- Low adherence to exclusive breastfeeding in Eastern Uganda:A community-based cross-sectional study comparing dietary recall since birth with 24-hour recall. BMC Pediatr. 2007;7(1):10. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-7-10

- [Google Scholar]

- Calculating Exclusive Breastfeeding Rates:Comparing Dietary “24-Hour Recall” with Recall “Since Birth” Methods. Breastfeed Med. 2016;11:514-518.

- [Google Scholar]

- A single 24 h recall overestimates exclusive breastfeeding practices among infants aged less than six months in rural Ethiopia. Int Breastfeed J. 2017;12(36):1-7. doi:10.1186/s13006-017-0126-9

- [Google Scholar]

- Exclusive breastfeeding in Sri Lanka :problems of interpretation of reported rates. 2009;3:3-5. doi:10.1186/1746-4358-4-14

- Exclusive Breastfeeding up to Six Months is Very Rare in Tanzania :A Cohort Study of Infant Feeding Practices in Kilimanjaro Area. 2015;3(2):251-258. doi:10.11648/j.sjph.20150302.24

- Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding in Nigeria 2011:2-9. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-11-2

- Prevalence and predictors of 6-month exclusive breastfeeding in a rural area in Egypt. Breastfeed Med. 2011;6(4):191-196.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and predictors of 6-month exclusive breastfeeding among Canadian women:a national survey. BMC Pediatr. 2010;10:20. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-10-20

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding practices among mothers in Goba district, south east Ethiopia :a cross-sectional study. Int Breastfeed J. 2012;7(1):1. doi:10.1186/1746-4358-7-17

- [Google Scholar]