Translate this page into:

Exploring Patients’ Needs and Desires for Quality Prenatal Care in Florida, United States

* Corresponding author email: cnreid@usf.edu

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background and Objective:

High-quality prenatal care promotes adequate care throughout pregnancy by increasing patients’ desires to return for follow-up visits. Almost 15% of women in the United States receive inadequate prenatal care, with 6% receiving late or no prenatal care. Only 63% of pregnant women in Florida receive adequate prenatal care, and little is known about their perceptions of high-quality prenatal care. Therefore, the objective of this study was to assess women’s perceptions of the quality of their prenatal care and to describe their preferences for seeking prenatal care that meets their needs.

Methods:

From April to December 2019, a qualitative study was conducted with postpartum women (n = 55) who received no or late prenatal care and delivered in Tampa, Florida, USA. Eligible women completed an open-ended qualitative survey and a semi-structured in-depth interview. The interview contextualized the factors influencing prenatal care quality perceptions. The qualitative data analysis was based on Donabedian’s quality of care model.

Results:

The qualitative data analysis revealed three key themes about women’s perceptions and preferences for prenatal care that meets their needs. First, clinical care processes included provision of health education and medical assessments. Second, structural conditions included language preferences, clinic availability, and the presence of ancillary staff. Finally, interpersonal communication encompassed interactions with providers and continuity of care. Overall, participants desired patient-centered care and care that was informative, tailored to their needs, and worked within the constraints of their daily lives.

Conclusion and Global Health Implications:

Women seeking and receiving prenatal care prefer a welcoming, patient-centered health care environment. These findings should prompt health care providers and organizations to improve existing prenatal care models and develop new prenatal care models that provide early, accessible, and high-quality prenatal care to a diverse population of maternity patients.

Keywords

Medicaid

Patient Preference

Patient-Centered Care

Pregnancy

Prenatal Care

Qualitative Research

Quality of Health Care

United States

1. Introduction

1.1. Background of the Study

Prenatal care has become one of the most widely used preventive health services in the United States.1 Despite recommendations for early prenatal care,2 approximately 1 in 16 live births (6.2%) in the United States was to women who received late or no prenatal care, and approximately 1 in 7 live births (14.8%) were to women who received inadequate prenatal care.3 In 2021, only 63% of pregnant women in the state of Florida received adequate prenatal care.4 Late initiation of prenatal care and inadequate prenatal care have been found to be associated with preterm births, low birth weight, and neonatal mortality.5–7 There is evidence that women’s perceptions of the quality of prenatal care may influence their initiation of timely prenatal care.8

While there has been a predominant focus on prenatal care adequacy, which includes the timing of the first prenatal visit and the number of prenatal visits throughout pregnancy, there has been limited research on women’s perceptions of the quality of prenatal care and their preferences for prenatal care.9–14 The World Health Organization (WHO) defines quality of care as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes.”15 Studies have shown that women desire quality prenatal care, which includes convenience of care,16 satisfaction with accessibility and continuity of care,9 high-quality patient–provider communication,10 and fewer prenatal visits than currently recommended by guidelines.13 Given this, the quality of prenatal care may be more important than the adequacy of prenatal care, particularly in encouraging women to participate in timely prenatal care. However, little is known about Florida women’s perceptions and preferences for quality prenatal care. Therefore, including women’s perceptions of the quality of prenatal care they receive and their preferences for meeting their prenatal care needs has the potential to promote timely initiation and consistency of prenatal care, with the goal of improving infant and maternal health outcomes. This is particularly important in Florida, where there are a large number of undocumented women, uninsured women, and lower-than-average rates of prenatal care initiation and adequacy.17,18

1.2. Objectives of the Study

We sought to assess how women in Florida perceive the quality of their prenatal care and to identify women’s preferences in prenatal care delivery to meet their needs. Donabedian’s seminal work on healthcare quality assessment proposed three domains for measuring quality of care,19 which were used by Sword et al.16 in a prenatal quality of care study: structure of care, clinical care processes, and interpersonal care processes. Over the last 30 years, this well-established framework has served as a foundation for healthcare quality assessment and research,16,20,21 and we will use it to identify patient-centered and self-reported outcome measures.

2. Methods

From April to December 2019, 55 postpartum women who received late or no prenatal care and delivered at Tampa General Hospital, a large, tertiary-care maternity hospital in Tampa, Florida, participated in this study. In 2019, Florida accounted for 6% of all births in the United States.22 Tampa General Hospital had approximately 6,500 births per year, making it one of the state’s largest delivery hospitals. The state of Florida had a population of 21 million people in 2020,23 and Tampa is the third largest city in Florida, with a population of 384,959 in 2020.24 A retrospective study design was used to investigate participants’ perceptions of the quality of their prenatal care. Participants first completed a demographic survey and an open-ended survey about the quality of their prenatal care. Semi-structured interviews were then conducted to further contextualize their open-ended survey responses to questions about prenatal care in terms of needs and desires. Thematic analysis of qualitative data using an a priori codebook was guided by Donabedian’s conceptualization of health care quality,19 as modified by Sword et al.16 This study was conducted concurrently with a separate research project on barriers to prenatal care access.25

2.1. Data Collection

Women >18 years old who delivered a live-born infant, could speak or read English or Spanish, and had not received first-trimester prenatal care defined by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists as care prior to 14 weeks were eligible to participate.2 A purposive sampling strategy was used to recruit women on-site at the postpartum floor of one hospital from a list of participants whose eligibility was established through an initial Epic electronic medical record (EMR) chart review.26

A total of 1,687 women were screened for eligibility through the initial chart review in Epic EMR. Of the 210 individuals who met the inclusion criteria and agreed to be approached by a member of the research team, 59 consented to participate in the study, and four were excluded due to not meeting inclusion criteria after enrollment. All participants signed an informed consent form to participate in this study. We then used the following data collection methods: (a) demographics and an open-ended self-report survey administered to participants by a member of the research team and (b) semi-structured interviews to elicit participants’ interpretations of survey results. Participant characteristics and corresponding interview data were combined and coded using MAXQDA 2020 analytical software.27 Each participant received a $25 Walmart gift card as compensation for participating.

Surveys

The demographic and open-ended survey was administered in English or Spanish, which included (a) demographic questions about age, race, ethnicity, nativity, marital status, income, education level, parity, and insurance type (before, during, and after pregnancy) and (b) open-ended survey questions about participants’ perceptions of prenatal care and potential changes in prenatal care experience.

Interviews

We also conducted semi-structured in-person interviews with each participant. The interviews were conducted by a bilingual research assistant (native Spanish speaker) trained in qualitative interviewing. Participants were asked a series of questions about their prenatal care experience that were similar to the open-ended survey questions. These open-ended semi-structured interviews were audio-recorded by a member of the research team upon survey completion. Confidentiality concerns were addressed before initiating audio-recordings.26 Almost all of the participants (n = 51) agreed to have their interviews audio-recorded. Three participants (IDs 15, 55, and 58) declined audio-recording, so detailed handwritten notes were taken during the interviews. The Spanish language interviews were directly translated from the Spanish recordings to the English transcripts. These transcripts were then checked for accuracy by a native Spanish-speaking research assistant.

2.2. Data Analysis

All interviews were audio-recorded and verbatim transcribed by a professional transcription service, with potential identifiers removed. We used a thematic analysis approach to analyze the data.28 Initially, we coded data using a priori codes based on Donabedian’s evaluation of the quality of care,19 as modified by Sword et al.,16 regarding how women perceive their prenatal care experience in terms of structural conditions, clinical processes, and health outcomes they encountered while seeking or navigating clinic visits. We also analyzed for emergent codes in the data and updated our codebook to include these codes and analytic and structural memos.28 The coded data were then analyzed into themes and subthemes28 under the three main categories informed by Donabedian’s model of quality health care as modified by Sword et al.16 Theoretical saturation was reached in the analysis.

Credibility for this study was achieved using the validation strategies of triangulation and peer debriefing.26 Data were triangulated between surveys, interviews, and field notes. Additionally, one-fifth (n = 10) of the transcripts were independently coded by another member of the research team to ensure reliability, resulting in 92% intercoder agreement. Coding differences were identified and discussed to achieve consensus on the final codebook.

2.3. Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the University of South Florida Institutional Review Board.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

The study included 55 women who received late or no prenatal care before giving birth at a large Tampa maternity hospital. The majority of participants were born in the United States (n = 33, 60%), had an average age of 29 years old (SD = 6.03), and identified as White (n = 25, 45%; Table 1). The majority of participants identified as Hispanic/Latinx heritage (n = 28, 51%), with (43%) self-identifying as Mexican or of Mexican descent. Additionally, most participants had a high school education (n = 20, 36%), were single (n = 28, 51%), and did not have insurance 1 month prior to pregnancy (n = 22, 41%) but used Medicaid at the time of delivery (n = 37, 67%). On average, participants went to eight prenatal care appointments (SD = 3.3) and had their first prenatal care appointment 19.4 weeks (SD = 5.1, range 14–34 weeks with two participants with no prenatal care) into their pregnancy.

| Characteristic | N (%) or mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 29 (6) |

| Preferred language | |

| English | 43 (78%) |

| Spanish | 12 (22%) |

| Race | |

| White | 25 (45%) |

| Black | 11 (20%) |

| Asian | 1 (2%) |

| More than one race | 8 (15%) |

| Unknown or not reported | 10 (18%) |

| Identify as Hispanic/Latinxa | 28 (51%) |

| Hispanic/Latinx heritageb | |

| Mexican | 12 (43%) |

| Puerto Rican | 7 (25%) |

| Central American | 4 (14%) |

| Dominican | 3 (11%) |

| Cuban | 1 (4%) |

| More than one | 1 (4%) |

| Country of origin | |

| USA | 33 (60%) |

| Mexico | 6 (11%) |

| Puerto Rico | 5 (9%) |

| Honduras | 4 (7%) |

| Dominican Republic | 3 (5%) |

| El Salvador | 1 (2%) |

| Guatemala | 1 (2%) |

| Haiti | 1 (2%) |

| Syria | 1 (2%) |

| Educationd | |

| <High school | 18 (33%) |

| High school graduate | 20 (36%) |

| Some college | 14 (25%) |

| College or higher education | 3 (6%) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 28 (51%) |

| Married | 18 (33%) |

| Living with a partner | 9 (16%) |

| Type of insurance before pregnancy | |

| Self-pay | 22 (41%) |

| Medicaid | 19 (35%) |

| Private insurance | 6 (11%) |

| CHAMPUS or Tri-care | 2 (4%) |

| Medicare | 1 (2%) |

| Don’t know or other | 4 (7%) |

| Type of insurance at delivery (by chart review) | |

| Medicaid | 37 (67%) |

| Self-pay | 13 (24%) |

| Private insurance | 3 (5%) |

| CHAMPUS or Tri-care | 2 (4%) |

N=55. Participants were on average 29 years old (SD=6.03) and household income (median = $25,000; IQR = $9,200, $38,000). aValues reflect respondents who affirmed “yes” to the question “Do you consider yourself to be Hispanic/Latinx?” bTwenty-seven respondents skipped the Hispanic/Latinx heritage descriptive survey question because they did not identify as Hispanic/Latinx: missing=27 (49%). cReflects the number of participants and percentage of participants answering “yes” to question “Born outside the USA and Puerto Rico?” and recoded as foreign-born. dEducation variable derived from recoding answers to “How many years of schooling in total have you completed?” (mean=11.6, SD=2.8) and then collapsing those values into four categories.

3.2. Themes

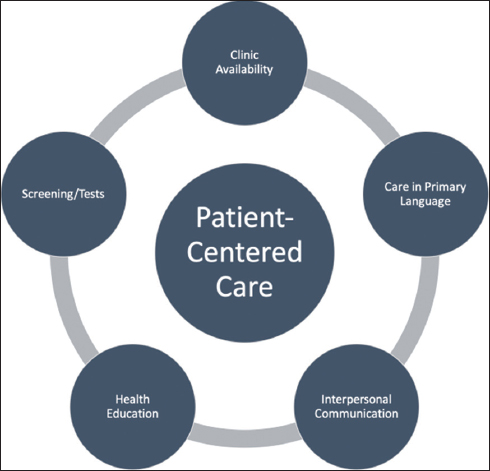

Table 2 summarizes the main themes and subthemes of women’s perceptions and preferences for high-quality prenatal care as guided by Sword et al.’s16 modified version of the Donabedian model of quality health care. Structure of care (at the clinic level), clinical care processes, and interpersonal communication were the three overarching themes that emerged from the data (Figure 1). In Table 2, we used supporting quotes to illustrate the patient’s perspectives, which are represented by (theme acronym, quote #).

| Theme and subthemes | ID | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Structure of Care (SC) | ||

| Clinic availability | SC1 | “I wanted to go for a more natural vaginal birth, so I was looking for a provider that was more inclined to support that. I went with a doctor that offered midwifery or midwives… The options were very limited. I also considered a birthing center which I eventually switched over to and those are even more limited. Most of the midwives are associated with OB-GYNs and hospitals. So, there’s very few birthing centers, as well.” (ID 38-Hispanic) |

| SC2 | “What I don’t like? I would say it wasn’t in a timely fashion for me to set an appointment…I didn’t think that it would take so long if I would’ve scheduled it at Genesis that I would be seen like two months later…I just didn’t know who to contact.” (ID 25-Non-Hispanic Black) | |

| SC3 | “So, we had scheduled our appointment. I had found out when I was eight weeks and it [appointment] wasn’t scheduled until 13 weeks, and when we went to our first appointment, I hadn’t been accepted by Medicaid yet. So, it would’ve been a lot of money out of pocket. So, we ended up having to reschedule it and then waiting until we got accepted for Medicaid.” (ID 28-Hispanic) | |

| SC4 | “Well… I went back and looked, and my first ultrasound was actually February 4th, so that was like eight weeks. But that was just like a confirmation of pregnancy before they would start me in prenatal care, and then that was a month later, so that’s why I ended up like being 12 or 13 [weeks].” (ID 36-Non-Hispanic White) | |

| Clinical Care Processes (CCP) | ||

| Screening and medical assessments | CCP1 | “[Knowing] the status of the baby if he’s growing right, if he has any defects going on. Me, to see if I have any health issues while I’m carrying the child because your body can change. It’s just basically knowing about my health while I’m pregnant. That’s about it.” (ID 25-Non-Hispanic Black) |

| CCP2 | “Like I wanted to know … like what will happen with the baby, like if they can see in the ultrasound. But they didn’t have that, they just had like checking the heartbeat and that’s it. They just sent me here-- like the next appointment…they just did the ultrasound, that was the only time I did have an ultrasound. But I wish I could’ve seen more of my baby even before anything.” (ID 12-Hispanic) | |

| CCP3 | “Absolutely. I was left on a medication called Lamictal…a folic acid antagonist, so what that means is it increases the chances of my child having spina bifida, and because of this, I was denied at two OB-GYN clinics…I wish that both of the original clinics that denied me would have been able to inform me on the first phone call that they would not accept a patient who had these risk factors and would have been able to give me a clear direction to someone who would accept somebody in my situation. Also, I would have wished that they would have understood how simple it would be to deem me not high risk because all it took was an ultrasound for them to deem me fine, that my baby was safe. I wasn’t in harm’s way. There was nothing that would have deemed this pregnancy high-risk. It would have been a very simple task. That, I wish is what I could have changed.” (ID 29-Non-Hispanic White) | |

| CCP4 | “Uh *exhale*, the prescription process, whenever I went and they would change my – my prescriptions or, you know, they start you out on the prenatal vitamins all the time, like every time I got a prescription it wasn’t able to be filled like at my pharmacy that I go to…I think it would have been more convenient if I’m going to this clinic one or two times a week that they have a pharmacy on site that carry the medications that are prescribed for pregnant females.” (ID 18-Hispanic) | |

| Health education concerns | CCP5 | “…so, they had done a blood test. It was—I thought that it was for the baby. They looked into it and found out I had [removed to maintain anonymity] and other than that? They have been great helping me learn about the baby and how to be a mom. It’s my first time with a kid…They actually helped me a lot thorough the process of it—becoming a mom and going through my depression stage because of the medicines that I take… Depression was like a huge thing in my pregnancy that I was scared that she [the baby] was going to catch it. So, they uh, come in and sat me down and we talked about every two to three times a month about it. So, it made me feel a lot better, knowing that they cared like that. It’s that I don’t really like taking pills, so the fact they actually sat me down and talked about it was really helpful. I mean, I have family at home, but they are working, and they don’t really have time for that—they got this and this to do. So, with them, they just sat me down and we talked about it. And they helped me understand more about the pregnancy.” (ID 54-More than one race) |

| CCP6 | “So, I was a first-time mom so I didn’t know a bunch of the risks and all that and stuff like that - like that needed to be. I knew that you couldn’t take like certain pain killers and stuff like that but not in depth.” (ID 28-Hispanic) | |

| CCP7 | “To me, it seemed like every time you go there, they tell you the same information over and over again. So, I feel like they need to do other stuff within your visits…To me, it’s just they tell you the weight and the same stuff that you know every time. I think that they need to do more within the visits.” (ID 05-Non-Hispanic Black) | |

| CCP8 | “Through Medicaid. I had done research. I went ahead and looked online myself and seen what all our Medicaid covers and what they provide so that I could benefit from every little thing that they have because I knew I was going to need everything that I can get. There weren’t any pamphlets that notified me of these things. These are things that I had to do on my own, and that’s another barrier. I feel like there should be more outreach program and more people get out giving knowledge about - making people knowledgeable about what health benefits they have access to because the lack of knowledge is like the biggest problem. People aren’t knowledgeable about the care that they can receive and so they’re not getting it.” (ID 47-Non-Hispanic Black) | |

| Interpersonal Communication (IC) | ||

| Impersonal care | IC1 | “Well, what I would change about the clinic, of course the doctors…the doctor that was there at first was rude. I don’t like it when you’re rude and disrespectful and just act like you don’t care. This is your job. This is what you have to do. You know what you basically signed up for and you know what you’re going to come here to do. If you don’t want to do your job, why are you here?” (ID 33-Hispanic) |

| IC2 | “The staff from the other two clinics treated me very poorly based on the judgment that I was a bad mother for getting pregnant while on a medication that could cause something as detrimental to my child as spina bifida. They treated me very unkindly and that was probably the biggest factor that I did not like. They judged me very heavily and it was a feeling I would never like to repeat for myself or anyone else…Then at the second office, the office staff, they are very judgmental. Thankfully, the doctor was not judgmental, but they were very unkind. They did not wish to speak to me any further about things such as, “Why would you not have gotten care before this?” The second clinic stated that, “How could you go so long without care,” which I informed them that I had previously been refused….” (ID 29-Non-Hispanic White) | |

| IC3 | “I just thought they were always in a rush because they have other people to assess…I wish like they would’ve told me more about what was going on.” (ID 12-Hispanic) | |

| IC4 | “We see too many different doctors. I don’t like that because I feel like they don’t know me personally and they don’t know what’s going on or how I feel…You can tell which doctor is very interested in you and your care. The doctors are like 10 minutes and then it’s like, “Okay, see you later,” out the door…You can see the same doctor or at least three doctors instead of 10 doctors. Also, the doctors that you see, should be one of the doctors that deliver your baby because I see all these different doctors, but that wasn’t even the doctor that delivered my baby. I don’t even know her. I’ve never even seen her… [so] you are nervous because you don’t know anything about her. You really can’t trust a person you don’t know.” (ID 40-Hispanic) | |

| Positive relationship dynamics | IC5 | “It was just like the staff was really - they made me feel comfortable. Also, when I came in, they knew exactly who I was and they made sure I was checked in properly, made sure I was in my appointment on time. They made sure that I didn’t stay over any longer, and they were just all nice, smiling, and every time I left, they told me, “Goodbye. Have a nice day. See you later.” No one was rude or mean or anything… They didn’t make me feel uncomfortable and make me not want to go to my appointments. I made it to mostly every appointment…” (ID 24-Non-Hispanic Black) |

| IC6 | “They made me feel actually safe and they broke everything down to make sure I understood like what was going on and just like the plans that they have for me and during the pregnancy.” (ID 20-Hispanic) | |

| IC7a IC7b | “They treated me well--excellently—very well when they took care of me. One experience that I liked? The nurses were excellent with me. They showed me how I was doing in my pregnancy…When I left, I felt fine. They treated me very well.” (ID 58-Hispanic) “I really like the midwives because they’re much more understanding than the doctors. They usually take a lot more time to be with each patient and address their concerns. They’re usually much more open to actually discussing issues or procedures…one of the midwives, which I actually saw her for most of my appointments there…She took the time to make sure that my medications were working for my mental health and just – there was one appointment where I just sat there and complained to her about all the things going wrong in my life [Laughter] and she just listened….” (ID 51-Hispanic) | |

| IC8 | “I liked the prenatal care and the visits…I’ve been going to them since I had my first kid, which was I was like 17, so they’re like my only experience really. All the doctors are really nice. Everybody is really sweet, you know what I mean? Like they take really good care of you; I love that about it. When the doctors do see you, they make sure they go over like everything, like if I have any concerns, they make sure they address every single concern. They don’t really like push me off or rush me out, you know what I mean?” (ID 23-Non-Hispanic Black) | |

| Language barriers | IC9 | “Communicating with the nurses is hard when you don’t speak English.” (ID 19-Hispanic) |

| IC10 | “When I came here for the first time for the ultrasound, I did not understand much of what they were telling me about the ultrasound. I told the doctor, but he was rude, very blunt, when he said to me that the baby might come sick. I mean, what I understood from him was that it [the baby] was coming sick…. I do not know if it was him that did not explain it well or if I understood it wrong).” (ID 11-Hispanic) | |

- Patient-centered care. Overarching themes that emerged from the study data.

Structure of care

Structural conditions shape care environments, which influence how individuals perceive access to and the quality of care available to them. The relevant subtheme included attitudes toward clinic availability.

Clinic availability

The subtheme of clinic availability includes attitudes and lingering desires among women who were unable to schedule their first prenatal care visit or subsequent prenatal visits earlier in their pregnancy. Most participants reported long wait times to be scheduled for their first and subsequent prenatal visits due to clinics being fully booked, which was attributed to several factors. In particular, women reported limited and inconvenient clinic hours that were incompatible with their schedules and the inability to schedule appointments with preferred providers or clinics (Structural Conditions [SC] 1). However, most of these participants opted to wait until their preferred clinic became available, based on the perceived quality of care and rapport with doctors. Additionally, women had difficulty determining who to talk to and how to schedule an appointment (SC2). The time it took to receive Medicaid and for providers to accept Medicaid was also associated with delays in scheduling the first prenatal appointment (SC3). Furthermore, one participant attributed the requirement of the clinic that her pregnancy be confirmed before scheduling her first prenatal visit to be the cause of her delay in prenatal care (SC4). Overall, participants reported long wait times during prenatal visits as a negative prenatal care experience.

Clinical care processes

Clinical care processes refer to the application of medical knowledge and clinical procedures implied in the provision of care.19 Relevant subthemes within clinical care are (a) screening and medical assessments and (b) health education concerns. During the interviews, participants discussed their attitudes and lingering desires for health promotion, information sharing, clinical testing, and medical assessments that are expected during prenatal care.

Screening and medical assessments

This subtheme frames attitudes toward screening tests and health assessments and lingering concerns about the types of knowledge and health assessments available to pregnant women, resulting in later prenatal care. Overall, participants of all races wanted to know their baby’s and their own health status during pregnancy through screenings and medical assessments. Participants reported that hearing their baby’s heartbeat and having several ultrasounds done throughout the pregnancy provided them with the most information about their baby’s health status, which they attributed to the quality of prenatal care (Clinical Care Processes [CCP] 1). However, some women reported only hearing their baby’s heartbeat but not receiving sufficient ultrasounds to ensure their baby’s health (CCP2). Perceived barriers to receiving these ultrasounds were described as a result of lacking health insurance and being scheduled for tests and ultrasounds separately from regular prenatal appointments. Similarly, blood draws though understood to be necessary, patients complained about how uncomfortable they were, and the results were not discussed in a timely manner. Participants of all races expressed their ability to address maternal health issues and fears. Minority participants valued the availability of prescribed medication at the clinic where they received prenatal care (CCP4).

Health education concerns

During prenatal care appointments, transparency and information on treatments and services improve perceptions of approachability to health care services during pregnancy.29 Generally, all participants valued and desired health information. Concerns about health information included pregnancy, prenatal care, Medicaid, and access to health services. Some participants reported receiving desired information and having pregnancy-related concerns addressed. For example, a multiracial participant found her providers to be helpful in educating her about her diagnosis, medication, and depression associated with her illness (CCP5). Despite some participants’ positive experiences with receiving information about their health and available services, participants of all races felt uninformed about clinical care processes. Participants, for example, desired more information about disease risk factors, medication risks during pregnancy, nutritional information, services provided, and information delivered in a clear manner (CCP6). Participants also preferred earlier access to information and disliked receiving the same information at each visit (CCP7). Although some minority women relied on Medicaid for health and service information, some had difficulty understanding Medicaid benefits and coverage (CCP8).

Interpersonal communications

Interpersonal communication dynamics reflect negative and positive interactions with providers, which encourage or discourage them from seeking or remaining in prenatal care.

Impersonal care

Impersonal care referred to the negative interactions and relationships that women had with their healthcare providers while receiving prenatal care. Provider professionalism and a lack of continuity of care with the same provider were related to quality of prenatal care. Participants reported a lack of provider professionalism as the provider being rude (Interpersonal Communications [IC] 1), dismissive, or judgmental. For example, a White participant felt judged by staff at several clinics about her pregnancy situation, which influenced her perception of the quality of prenatal care she received (IC2). The desire of minority participants to not feel rushed or juggled around during their prenatal visits was also related to provider professionalism (IC3).

The lack of continuity of prenatal care providers was perceived negatively in terms of prenatal care quality. Participants of all races valued seeing the same provider at each prenatal visit and regarded one-on-one doctor–patient visits as more personal, attributing this to the development of trust and rapport with their provider (IC4).

Positive relationship dynamics

Positive relationships include efforts to promote health and knowledge sharing in a positive and welcoming environment. Participants reported that nice, friendly, and supportive providers and staff created a positive environment for prenatal care. A participant stated that the positive environment encouraged her to keep her prenatal care appointments (IC5). Participants receiving prenatal care valued providers who were considered understanding and shared necessary information in a comprehensible manner (IC6). However, some patients perceived a more positive relationship dynamic with nurses than with doctors because nurses were perceived to be more helpful and understanding (IC7). A history of developing a relationship with a provider during previous prenatal visits reinforced the continuation of positive relationship dynamics with the same provider (IC8).

Language barriers

Language barriers (in this case, Spanish) hinder one’s ability to understand the information shared. The subtheme of language barriers addressed language-related issues in obtaining prenatal care via communication with providers and clinical staff. Some Spanish-speaking participants found it difficult to communicate with clinic staff in English (IC9), while others had no issue because clinic staff spoke Spanish. Language barriers, on the other hand, may contribute to confusion and miscommunication of health information for women seeking prenatal care (IC10).

4. Discussion

We used Donabedian’s model of health care quality19 to assess how women in Florida perceive the quality of their prenatal care and to identify women’s prenatal care preferences. The overarching theme was a desire for patient-centered care. Patient-centered care is defined as care that is consistent with patients’ values and preferences and includes shared decision making between the provider and the patient.30,31 We found that women wanted care that included screening and medical assessments, health education, easy clinic access, and was provided in their native language by providers who were personal and supportive. These elements are consistent with the framework of patient-centered care.30,31

In comparison to Sword et al.’s16 research in Canada, our participants wanted similar elements in prenatal care. Both groups desired providers who interacted with them respectfully, took the time to talk with them rather than rushing through the visit, and provided emotional support. Both groups valued the sharing of health information, screenings and assessments, and continuity of care. Unlike in Sword et al.’s16 study, our participants reported more scheduling issues, such as long wait times for appointments and only being seen once in clinic, which may be related to the different health care delivery systems in each study. We also noted several issues with access, which are discussed in greater detail in a separate article.25 Due to the diversity of our sample, we found that language barriers for Spanish speakers were an important factor in providing effective prenatal care.

These findings suggest new avenues for further advancement in prenatal care and modifiable factors in the clinical setting. We identified numerous areas for quality improvement in prenatal care delivery that could be incorporated into new prenatal care models or improved upon existing ones. For example, individual prenatal care could be improved by promoting interpersonal care, relationship building, and modifying scheduling to allow for provider continuity. Adding after-hour clinical appointments or more flexible appointment scheduling could also improve care and increase prenatal care visit uptake. Women of color had difficulties fitting in with clinic times due to competing life demands, whereas health education concerns were shared more evenly across groups.

Additionally, these elements of quality prenatal care produce patient-oriented outcomes for new prenatal care models, such as virtual prenatal care, group prenatal care, and enhanced prenatal care models. While some Black and Hispanic participants may have reported different issues than White participants, our findings cannot be generalized. As a result, further research is required to delve deeper into each of these elements to determine measurable outcomes. Including patient-centered outcomes in future evaluations of care models will allow for improved quality of care and prenatal care that women want to access and use during their pregnancy. It is also imperative that we better understand whether specific needs of women of color differ from those of White women beyond the overt, such as language. Cultural nuances of beliefs about pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes, for example, may need to be incorporated once they are better understood; however, these were not identified in our study. These patient-oriented outcomes can be combined with Peahl et al.’s13 research on patient preferences for prenatal care delivery to develop enhanced patient-centered prenatal care models.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

Our study has several strengths and weaknesses. Participants were very diverse, including non-English speakers. Because many prenatal care models and studies have excluded non-English speakers,13,32,33 we sought to include these women and other low-income women of color because these subgroups have the highest maternal mortality in the United States.34 This study had some limitations. First, recall bias was possible because this study relied on postpartum women’s recall of prenatal care experiences. Second, our sample was drawn from a single large tertiary care hospital, which limits the study’s generalizability to other locations. Third, we acknowledge that women in different communities may have different prenatal care preferences and all prenatal care models and methods must be tailored to each community. Participants may express or omit opinions on aspects of care received from a health professional based on cultural norms, and thus, responses may have been subject to social desirability bias. Another study limitation is that some women chose not to specify their racial or ethnic identity.

5. Conclusion and Global Health Implications

This study has national and global implications for ensuring timely access to high-quality prenatal care to increase the likelihood of desired pregnancy and birth health outcomes. We identified numerous areas for quality improvement in the provision of prenatal care that could be incorporated into new prenatal care models or improved upon existing models used globally. For example, individual prenatal care could be improved by modifying scheduling and reducing the number of scheduled visits in high resource settings to the WHO recommended eight visits,35 allowing for provider continuity and promoting interpersonal interactions between prenatal care providers and patients.36 Improving access to early, timely prenatal care was also identified as a need, with many respondents identifying barriers to initial prenatal care access due to healthcare system structural barriers or insurance issues. Clinical care pathways must be improved to facilitate early care and ensure that navigating the health care system does not impede timely care. Positive, caring, and respectful health care providers may influence timely prenatal care uptake and patient satisfaction.37 Patient concerns about health education should be addressed using appropriate health education strategies throughout the prenatal and postpartum periods.38 It has also been shown that it is imperative that we better understand if specific needs of women of color differ from those of White women beyond the overt, such as language, because there is evidence that the prenatal care needs of many Black pregnant women are not being met.39 Although not identified in our study, patient socio-cultural norms related to pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes should be taken into account when providing prenatal care.40 These elements of quality prenatal care create patient-oriented outcomes to improve the development of new prenatal care models, such as virtual prenatal care, group prenatal care, or enhanced prenatal care models.40 To improve early, accessible, and high-quality prenatal care for a diverse patient population, providers and organizations should consider how patients access prenatal care appointments, align the services provided during the visit with patient expectations, and practice effective interpersonal communication and relationship-building.

Acknowledgments:

None.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Financial Disclosure: Nothing to declare.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by the University of South Florida Seed Grant.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the University of South Florida Institutional Review Board.

Disclaimer: None.

References

- The changing pattern of prenatal care utilization in the United States, 1981-1995, using different prenatal care indices. J Am Med Assoc. 1998;279(20):1623-1628. doi:10.1001/jama.279.20.1623

- [Google Scholar]

- 2012. Guidelines for Perinatal Care. (Seventh Ed). https://www.buckeyehealthplan.com/content/dam/centene/Buckeye/medicaid/pdfs/ACOG-Guidelines-for-Perinatal-Care.pdf

- Florida Health CHARTS. Published 2023 https://www.flhealthcharts.gov/ChartsReports/rdPage.aspx?rdReport=Birth. Dataviewer&cid=615&drpCounty=29

- Prenatal care utilization in mississippi:Racial disparities and implications for unfavorable birth outcomes. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15(7):931-942. doi:10.1007/s10995-009-0542-6

- [Google Scholar]

- Health Care Disparity and State-Specific Pregnancy-Related Mortality in the United States, 2005-2014. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(4):869-875. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001628

- [Google Scholar]

- Inadequate prenatal care utilization and risks of infant mortality and poor birth outcome:A retrospective analysis of 28,729,765 U. S. deliveries over 8 years. Am J Perinatol. 2012;29(10):787-793. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1316439

- [Google Scholar]

- “Weighing up and balancing out”:A meta-synthesis of barriers to antenatal care for marginalised women in high-income countries. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;116(4):518-529. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.02067.x

- [Google Scholar]

- More than a “number”:perspectives of prenatal care quality from mothers of color and providers. Womens Health Issues. 2018;28(2):158-164. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2017.10.014

- [Google Scholar]

- African American women and prenatal care:perceptions of patient-provider interaction. West J Nurs Res. 2015;37(2):217-235. doi:10.1177/0193945914533747

- [Google Scholar]

- Qualitative comparison of women's perspectives on the functions and benefits of group and individual prenatal care. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2016;61(2):224-234. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12379

- [Google Scholar]

- Women's experience of prenatal care:an integrative review. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2009;54(3):226-237. doi:10.1016/j.jmwh.2009.02.003

- [Google Scholar]

- Patient preferences for prenatal and postpartum care delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(5):1038-1046. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000003731

- [Google Scholar]

- Women's narratives on quality in prenatal care:A multicultural perspective. Qual Health Res. 2008;18(11):1586-1598. doi:10.1177/1049732308324986

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Published 2022 https://www.who.int/health-topics/quality-of-care#tab=tab_1

- Women's and care providers'perspectives of quality prenatal care:A qualitative descriptive study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12(1):29. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-12-29

- [Google Scholar]

- PeriStats. Published 2020 https://www.marchofdimes.org/peristats/ViewTopic.aspx?reg=12&top=5&lev=0&slev=4

- Women's Health Insurance Coverage. Published 2020 https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/fact-sheet/womens-health-insurance-coverage-fact-sheet/

- The Quality of Care:How Can It Be Assessed? JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 1988;260(12):1743-1748. doi:10.1001/jama.1988.03410120089033

- [Google Scholar]

- Tell me what you mean by “Si”:perceptions of quality of prenatal care among immigrant Latina women. Qual Health Res. 2001;11(6):780-794. doi:10.1177/104973201129119532

- [Google Scholar]

- Antenatal care satisfaction in a developing country:a cross-sectional study from Nigeria. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):368. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5285-0

- [Google Scholar]

- Births:Final Data for 2019. Natl Vital Stat Reports. 2021;70(2) https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/index.htm

- [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Census Bureau QuickFacts:Florida. Published 2022 https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/FL/POP010220

- U. S. Census Bureau QuickFacts:Tampa city, Florida. Published 2022 https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/tampacityflorida

- Health care system barriers and facilitators to early prenatal care among diverse women in Florida. Birth. 2021;48(3):416-427. doi:10.1111/BIRT.12551

- [Google Scholar]

- Research Design :Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (Fifth). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE; 2018.

- The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers 2015

- Perceptions of barriers to accessing perinatal mental health care in midwifery:A scoping review. Midwifery. 2019;70:106-118. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2018.11.011

- [Google Scholar]

- Scoping review of patient-centered care approaches in healthcare. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):271. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-14-271

- [Google Scholar]

- Person-Centered Care:A Definition and Essential Elements. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(1):15-18. doi:10.1111/jgs.13866

- [Google Scholar]

- Randomized comparison of a reduced-visit prenatal care model enhanced with remote monitoring. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(6):638.e1-638.e8. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.06.034

- [Google Scholar]

- A mobile prenatal care app to reduce in-person visits:Prospective controlled trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2019;7(5) doi:10.2196/10520

- [Google Scholar]

- Racial/ethnic disparities in pregnancy-related deaths - United States, 2007-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(35):762-765. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6835a3

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience 2016

- Randomized comparison of a reduced-visit prenatal care model enhanced with remote monitoring. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(6):638.e1-638.e8. doi:10.1016/J. AJOG.2019.06.034

- [Google Scholar]

- Attitudes and behaviours of maternal health care providers in interactions with clients:a systematic review. Global Health. 2015;11(36) doi:10.1186/S12992-015-0117-9

- [Google Scholar]

- Health education strategies targeting maternal and child health:A scoping review of educational methodologies. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(26):e16174. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000016174

- [Google Scholar]

- Experiences with prenatal care delivery reported by black patients with low income and by health care workers in the US:a qualitative study. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(10):E2238161. doi:10.1001/JAMANETWORKOPEN.2022.38161

- [Google Scholar]

- Provision and uptake of routine antenatal services:a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;6(6):CD012392. doi:10.1002/14651858 CD012392. PUB2

- [Google Scholar]