Translate this page into:

Household Headship and Infant Mortality in India: Evaluating the Determinants and Differentials.

✉Corresponding author email: kakoli.26nov@gmail.com

Abstract

Background:

There has been ample discussion on the levels and trends of infant mortality in India over time, but what remains less explored are, the differentials in infant mortality according to household headship. This paper examined the differences in the determinants of infant mortality between maleheaded households (MHH) and female-headed households (FHH).

Methods:

The study used Cox proportional hazard model to examine the determinants of infant death, and Kaplan-Meier estimation technique to examine the survival pattern during infancy using data from Indian National Family Health Survey (2005-06). The analysis is restricted to women who had at least one live birth in the five years preceding the survey.

Results:

The study observed that household size and number of children below five are significant risk factors of infant mortality in MHH while length of previous birth interval is the only significant risk factor of infant death in FHH.

Conclusions and Global Health Implications:

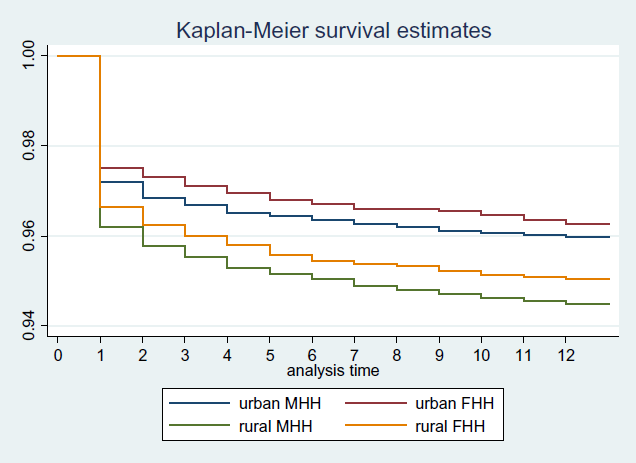

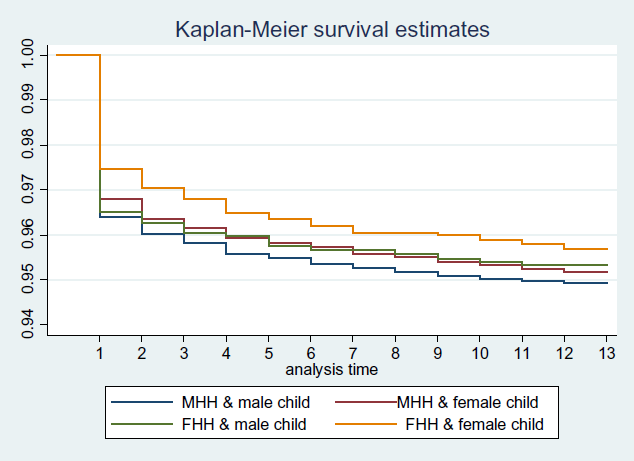

The results indicate that children from FHH have higher survival probability at each age than children from MHH irrespective of place of residence and sex of the child.

Keywords

Male-headed household

Female-headed household

Infant mortality

India

Economic condition

Background

Over the past several decades, infant and child mortality remain one of the major public health challenges faced by the world. Infant mortality rate may be an indicator of how a society meets the needs of its people[1] indicator of deprivation,[2] unmet health needs and unfavourable environmental factors[3] and a sensitive indicator of country's health.[4] There is consistent decline in infant mortality in India since 1970's. From 127 deaths per thousand live births in 1971, it has declined to 42 deaths per thousand live births in 2012[5] showing annual decline of 1.6 percent. Although, infant mortality has declined over time, but at the current pace, India is unlikely to achieve the Millennium Development Goal (MDG-4) of reducing infant mortality to 27 per thousand live births by 2015.[3]

The studies on infant mortality in India, has focused on the socio-economic and demographic factors that may have a direct or indirect effect on infant death. It is documented by different researchers that household environment, economic condition, place of residence, education of mother, and health care utilization; are significant determinants of infant mor- tality.[6-8] Recently, household headship as a factor of infant mortality has gained importance among the researchers,[9-12] but studies exploring the association between infant mortality and type of household headship are limited, at least in India. The changes in socio-economic conditions of the country has resulted in a continuous increase in female-headed households (FHH).[9,13] According to the census of India, 2011, about 27 million (11 percent) of the total households in India is headed by women. Earlier studies from developed and developing countries suggested both positive and negative associations between female headship and economic condition of household.[9,10,13-17] On the basis of the above discussion, this study examined the association between household headship and infant mortality in India.

Methods

The study is based on the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3, 2005-06) covering 109,041 households with 11 percent FHH from all the states of India. NFHS is the most comprehensive survey that provides information on death at the household level, specifically, the exact age at death of infants for each month till the first year of life. This analysis is restricted to ever-married women who had at least one live birth for a period of five years preceding the survey, and recorded 51,555 live births and 2500 infant deaths during the same period.

The variables included in the study are place of residence, religion, caste, wealth index, household size, age of the household head, number of eligible women in the household, number of children below five, age at first birth, antenatal care, education of mother, exposure to mass media, total number of children ever born, place of delivery, and preceding birth interval. Cox proportional hazard model was used to examine the determinants of infant mortality. In addition, Kaplan Meier survival curves are drawn to examine the pattern of survival at exact ages. Chi-square test was used to examine the association of sex of the household head with some selected household and individual level variables.

Results and Discussion

The results are presented in three sub-sections. The first section deals with the differences in socio-demographic characteristics according to household headship. The second section discusses the determinants of infant mortality, and the last section shows the survival pattern during infancy according to household headship.

Socio-demographic characteristics.

The differences observed in socio-demographic characteristics between MHH and FHH are presented in Table 1. It was observed that, in FHH, percentage of home deliveries was high; and antenatal care and percentage of children ever breastfed was low than MHH. In addition, FHH had higher percentage of illiterate mothers (69%) than MHH (63%). Seventy percent of FHH had no exposure to mass media and only six percent had exposure to both radio and television. On the other hand, 13 percent of MHH had exposure to both radio and television. FHH also performed better in certain indicators; for example, higher percentages of children were immunized and lower percentages of children were born with short birth interval. The results further indicate differences in economic condition of FHH and MHH. The study observed that the FHH with low economic status reported higher percentage of infant deaths. Earlier studies also revealed that FHH are generally poorer than MHH[18].

| Background Characteristics | Household who experienced infant death | |

|---|---|---|

| Male Headed Household | Female Headed Household | |

| Sex of the child | ||

| Male | 50.2 | 49.9 |

| Female | 49.8 | 50.1 |

| Place of Delivery | ||

| Home | 69.3 | 71.1 |

| Health Facility | 30.7 | 28.9 |

| Preceding Birth Interval | ||

| <2 years | 44.7 | 39.7 |

| 2-3 years | 41.8 | 50.3 |

| 4 or more years | 13.5 | 10.0 |

| Birth Order | ||

| 1 | 32.6 | 30.6 |

| 2-3 | 35.5 | 37.7 |

| 4 & above | 31.8 | 31.7 |

| Antenatal care | ||

| Yes | 69.9 | 59.7 |

| No | 30.1 | 40.3 |

| Children ever breastfed | ||

| Yes | 65.8 | 63.8 |

| No | 34.2 | 36.2 |

| Immunization | ||

| Yes | 12.8 | 15.0 |

| No | 87.2 | 85.0 |

| Age at First Birth | ||

| Less than 18 | 38.1 | 39.6 |

| 18-24 | 56.8 | 56.0 |

| 25 & above | 5.0 | 4.4 |

| Age at Marriage | ||

| less than 18 | 67.8 | 69.9 |

| 18-24 | 30.6 | 28.4 |

| 25 & above | 1.5 | 1.7 |

| Education of Mother | ||

| No Education | 63.1 | 69.3 |

| Primary | 15.0 | 10.8 |

| Secondary | 20.2 | 18.3 |

| Higher | 1.7 | 1.6 |

| Mass Media Exposure | ||

| No Exposure | 56.3 | 70.4 |

| Either Radio or TV | 31.1 | 23.6 |

| Both Radio & TV | 12.7 | 6.0 |

| Children Ever Born | ||

| 1 | 12.5 | 9.3 |

| 2 | 26.3 | 33.5 |

| 3 | 18.3 | 17.0 |

| 4 & above | 43.0 | 40.1 |

| Place of Residence | ||

| Urban | 18.1 | 15.6 |

| Rural | 81.9 | 84.4 |

| Religion | ||

| Hindu | 81.1 | 73.8 |

| Muslim | 14.6 | 23.9 |

| Christian | 1.5 | .5 |

| Others | 2.7 | 1.8 |

| Caste | ||

| Scheduled Caste | 24.4 | 26.7 |

| Scheduled Tribe | 12.6 | 9.3 |

| Other Backward Classes | 40.6 | 38.1 |

| Others | 22.3 | 25.9 |

| Wealth Index | ||

| Poorest | 32.6 | 36.1 |

| Poorer | 26.6 | 35.4 |

| Middle | 20.4 | 9.8 |

| Richer | 13.4 | 1 1.5 |

| Richest | 7.0 | 7.2 |

Household headship and selected variables.

The results of chi-square test indicate significant association of household headship with infant mortality. Other variables like household size, number of women in 15-49 age-group, number of children below five years of age, religion, caste, wealth index, exposure to mass media, preceding birth interval, place of delivery, antenatal care, age at first birth, education of mother also showed significant association with infant mortality.

Infant mortality and household headship.

On the basis of the results obtained from Chi square test, the study further examined the association of different factors with infant death according to household headship. The adjusted and unadjusted hazard of infant death from MHH and FHH is presented in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. Unadjusted estimates indicate that household size, number of under-five children, age of the household head, wealth index, education of mother, age at first birth, length of preceding birth interval, antenatal care, and breastfeeding status all have independent effect on risk of infant death, in both MHH and FHH. On the other hand, rural residence increased the risk of infant death.

| Background Characteristics | Unadjusted | Household Factors | Maternal Factors | Child Factors | All factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household size | |||||

| 0-5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | -1.00 | ||

| 5+ | 0.67*** | 0.78*** | 0.55*** | ||

| Number of eligible women | |||||

| 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| more than 1 | 0.99 | 1 41*** | 1 74*** | ||

| Number of children under 5 | |||||

| 1 or 2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| more than 2 | 0.52*** | 0.50*** | 0.49*** | ||

| Age of the Household Head | |||||

| less than 35 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 35-50 | 0.89** | 1.00 | 0.98 | ||

| 50+ | 0.804** | 1.00 | 0.96 | ||

| Religion | |||||

| Hindu | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Muslim | 0.89* | 0.96 | 0.75* | ||

| Christian | 0.77*** | 0.80* | 0.91 | ||

| Others | 0.89 | 1.00 | 1.01 | ||

| Caste | |||||

| Scheduled Caste | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Scheduled Tribe | 0.86** | 0.91 | 1.12 | ||

| Other Backward Classes | 0.88** | 1.01 | 1.20 | ||

| Others | 0.70*** | 0.86* | 1.02 | ||

| Wealth Index | |||||

| Poorest | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Poorer | 0.97 | 1.02 | 1.08 | ||

| Middle | 0.77*** | .79*** | 0.91 | ||

| Richer | 0.60*** | .59*** | 0.74 | ||

| Richest | 0.41*** | .38*** | 0.73 | ||

| Place of Residence | |||||

| Urban | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Rural | 1.38*** | 0.99 | 1.03 | ||

| Education of Mother | |||||

| No Education | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Primary | 0.86** | 0.93 | 1.00 | ||

| Secondary | 0.56*** | 0.66*** | 0.74* | ||

| Higher | 0.28*** | 0.36*** | 0.40* | ||

| Age at first birth | |||||

| Less than 18 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 18-24 | 0.75*** | 0.93* | 0.83* | ||

| 25 & above | 0 51 *** | 0.84* | 0.69 | ||

| Children ever born | |||||

| 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 2 | 1.31*** | 1 .24*** | 1.07 | ||

| 3 | 1.57*** | 1.31 *** | 1.73*** | ||

| 4 & above | 2.1 8*** | 1 .64*** | |||

| Place of delivery | |||||

| Home | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Health Facility | 0.70*** | 0.79 | 0.83 | ||

| Previous birth Interval | |||||

| <2 years | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.000 | ||

| 2 or more years | 0.50*** | 0.65 | 0.42*** | ||

| Antenatal care | |||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.65*** | 0.83 | 0.93 | ||

| Children ever breastfed | |||||

| Yes | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| No | 16.84*** | 28.67 | 29.52*** | ||

***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.10

| Background Characteristics | Unadjusted | Household Factors | Maternal Factors | Child Factors | All factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household size | |||||

| 0-5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 5+ | 0.62*** | 0.97 | 0.59 | ||

| Number of women | |||||

| 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| more than 1 | 0.91 | 1.32 | 1.21 | ||

| Number of children under 5 | |||||

| 1 or 2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| more than 2 | 0.42*** | 0.40*** | 0.38 | ||

| Age of the household head | |||||

| less than 35 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 35-50 | 1.42* | 1.37 | 1.35 | ||

| 50+ | 0.88 | 1.16 | 1.32 | ||

| Religion | |||||

| Hindu | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Muslim | 0.88 | 1.21 | 0.89 | ||

| Christian | 0.57* | 0.53 | 0.51 | ||

| Others | 0.78 | 0.64 | 1.55 | ||

| Caste | |||||

| Scheduled Caste | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Scheduled Tribe | 0.78 | 1.00 | 0.88 | ||

| Other Backward Classes | 0.61 *** | 0.54*** | 0.83 | ||

| Others | 0.53*** | 0.72 | 1.28 | ||

| Wealth Index | |||||

| Poorest | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Poorer | 1.07 | 1.35 | 1.03 | ||

| Middle | 0.49*** | 0.54** | 0.69 | ||

| Richer | 0.48*** | 0.52** | 0.33** | ||

| Richest | 0.35*** | 0.35*** | 0.60 | ||

| Place of Residence | |||||

| Urban | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Rural | 1.33* | 0.83 | 0.80 | ||

| Education of Mother | |||||

| No Education | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Primary | 0.95 | 1.03 | 1.37 | ||

| Secondary | 0.47** | 0.54*** | 0.59 | ||

| Higher | 0.27** | 0.33*** | 0.21 | ||

| Age at first birth | |||||

| Less than 18 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 18-24 | 0.84 | 1.08 | 0.64 | ||

| 25 & above | 0.53** | 1.00 | 0.34 | ||

| Children ever born | |||||

| 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 2 | 1.71** | 1.61** | 1.10 | ||

| 3 | 2.14*** | 1.73** | 0.79 | ||

| 4 & above | 2.70*** | 1.93*** | |||

| Place of delivery | |||||

| Home | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Health Facility | 0.61*** | 0.71 | 1.09 | ||

| Previous birth Interval | |||||

| <2 years | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 2 or more years | 0.51*** | 0.66 | 0.40*** | ||

| Antenatal care | |||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.43*** | 0.56** | 0.73 | ||

| Children ever breastfed | |||||

| Yes | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| No | 19.30*** | 30.18*** | 29.30*** | ||

***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.10.

However, after adjusting for different household level factors, the increase in household size, number of children below five and improvement in economic condition significantly reduced the risk of infant death in MHH, while household size had no significant association with infant death in FHH. Similar results were observed from the adjusted effect of maternal characteristics for MHH and FHH. The results show that age of mother at first birth, education and number of children ever born are significant predictors for infant mortality.

Child-Level factors.

Differences were observed in the association of child level factors with risk of infant death. None of the child-related factors had significant association with the risk of infant death in MHH, but antenatal care and breastfeeding status of the child were significantly associated with risk of infant death in FHH. When all the factors were considered simultaneously, household size, number of eligible women, number of children below five, education of mother, previous birth interval and breastfeeding status remained significant predictors of infant mortality in MHH. For FHH, only duration of preceding birth interval and breastfeeding status of the child had significant association with risk of infant death.

Patterns of survival during infancy.

Urban children living in FHH has the highest probability of survival out of the four combinations of sex of the household head and place of residence (see Figure 1). The urban advantage in survival during infancy remains same. It may be postulated that female head of the household are more concerned about the type of care to be provided to the child during infancy, and the mother of the young child may feel comfortable in discussing different issues related to child care with an elderly female member of the household than an elderly male. As shown in Figure 2, female child in FHH enjoys some advantages in terms of survival during infancy. This may indicate that, along with the biological advantage of survival for a female over a male child, a newborn girl is not discriminated against in a FHH in providing necessary care during infancy.

- Survival pattern during infancy by place of residence in MHH and FHH, NFHS-3 (2005-06), India

- Survival pattern according to sex of the child in MHH and FHH, NFHS-3 (2005-06), India

Conclusions and Global Health Implications

The study observed that each of the risk factors had significant association with infant death in MHH and FHH as independent predictors. The differences emerged when the risk factors were adjusted for maternal, child and other household characteristics. In MHH, household size, number of eligible women, number of children below five years and economic condition are significant risk factors, when the model is adjusted for household factors. Among the maternal factors, increase in education of mother reduced risk of infant death while increase in average number of children born, elevated the hazard of infant death. When adjusted for all the study variables, household size, number of eligible women, number of children below five and child breastfeeding had significant association with infant death.

In FHH, economic condition of the household was the only significant risk factor for infant death when adjusted for the household characteristics. Again, education of mother and number of children ever born were significant risk factors when adjusted for maternal characteristics. Among the child related characteristics, child ever breastfed and antenatal care were significant risk factors for infant death. After adjusting for all the risk factors, breastfeeding status and length of previous birth interval were the only significant risk factors of infant death.

The study further observed that the pattern of survival also differ for FHH and MHH. Children had higher survival probability at each age in FHH than MHH irrespective of place of residence and sex of the child. Thus the paper concludes that the determinants of infant mortality should be examined according to household headship. Government should promote FHH and appropriate policies should be formulated to improve economic condition of FHH.

Conflict of Interest:

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding:

The authors have no financial assistance to carry out the research.

References

- Infant Mortality and the Health of Societies. Washington DC: The Worldwatch Institute 1981

- [Google Scholar]

- Social factors and infant mortality: Identifying high-risk groups and proximate causes. Demography. 1987;24:299-322.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infant and child mortality in India: Levels trends and Determinants. National Institute of Medical Statistics (NIMS), Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), and UNICEF India Country Office, New Delhi, India. 2012

- [Google Scholar]

- A study of district level development factors influencing infant mortality rate and life expectancy in the Indian Thar Desert. Journal of Rural and Tropical Public Health. 2006;5:42-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- What explains the rural-urban gap in infant mortality: Household or community characteristics? Demography. 2009;46(4):827-850.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Explaining the rural urban gap in infant mortality in India. Demographic Research. 2013;29(18)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Female-Headed Households, Poverty, and the Welfare of Children in Urban Brazil. Economic Development and Cultural Change. 1997;45(2):231-57.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lesotho's Household Structure: Some Reflections from the Household Budget Survey. In: Working Papers in Demography. Lesotho: National university of Lesotho; 1990.

- [Google Scholar]

- Household headship and child death: Evidence from Nepal. BMC International Health and Human Rights. 2010;10:13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Does living in female headed household lower child mortality? The case of rural Nigeria. The International Electronic Journal of Rural and Remote Health Research, Education, Practice and Policy. 2011;11:1635.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller E. The Economic Status of Female-Headed Households in Rural Botswana. Economic Development and Cultural Change. 1983;31(3):831-59.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Female Headship in India: Levels, Differentials an. Impact. Paper presented at the 25th conference of IUSSP in France 2005

- [Google Scholar]

- Female-Headed Households and Female-Maintained Families: Are They Worth Targeting to Reduce Poverty in Developing Countries? Economic Development and Cultural Change. 1997;45(2):259-80.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Widowhood and Poverty in Rural India: Some Inferences from Household Survey Data. Journal of Development Economics. 1997;54:217-234.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A comparison of female and male-headed households in Tanzania and poverty implications. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2006;38(3):327-339.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]