Translate this page into:

Mental Health in Developing Countries: Challenges and Opportunities in Introducing Western Mental Health System in Uganda.

✉Corresponding author email: jkopinak@hotmail.com

Abstract

Background:

Despite decades of disagreement among mental health practitioners and researchers in the Western world pertaining to the causation, classification and treatment of mental disorders there is an ongoing push to implement western mental health models in developing countries. Little information exists on the adaptability of western mental health models in developing countries.

Method:

This paper presents a review of the attempt to implement a western-oriented mental health system into a different culture, specifically a developing country such as Uganda. It draws upon an extensive literature review and the author's work in Uganda to identify the lessons learned as well as the challenges of introducing a western- oriented mental health system in a totally new cultural milieu.

Results:

There is recognition by the national government that the challenges faced in mental health services poses serious public health and development concerns. Efforts have and are being made to improve services using the Western model to diagnose and treat, frequently with practitioners who are unfamiliar with the language, values and culture.

Conclusions and Global Health Implications:

Uganda can continue to implement the Western mental health practice model which emanates from a different cultural base, based on the medical model and whose tenets are currently being questioned, or establish a model based on their needs with small baseline in-country surveys that focus on values, beliefs, resiliency, health promotion and recovery. The latter approach will lead to a more efficient mental health system with improved care, better outcomes and overall mental health services to Ugandan individuals and communities.

Keywords

Mental health

Models

Implementation

East Africa

Uganda.

Background

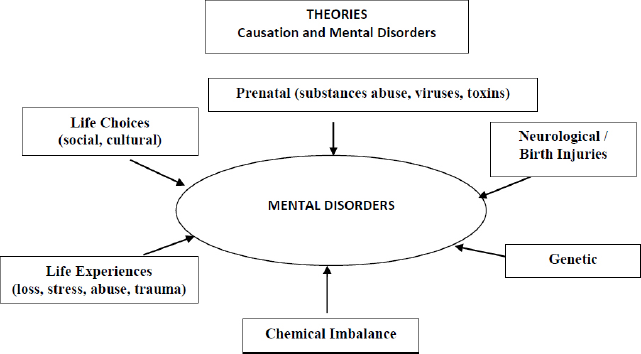

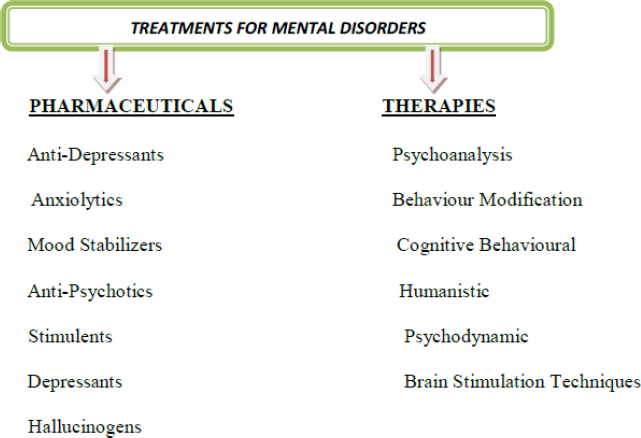

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) ‘mental health is a state of well-being in which every individual is able to realize his/her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, work productively and make a contribution to his/ her family and community'.[1] Mental disorder is defined by psychiatric experts as a ‘clinically significant behavioral or psychological syndrome with sufficient personality, mind and/or emotional disorganization that seriously impairs individual and social function with an increased risk of suffering, death, pain, disability or loss of freedom'.[2] Despite these clear definitions, the mental health field has been embroiled in long-term disagreement pertaining to the exact causes of many mental disorders with some experts believing that dysfunction is biological (genetic, chemical imbalance in the brain), others to life events and still others to a combination of these factors. These differing views have led to a plethora of treatments that includes many forms of psychotherapy, the use of pharmaceuticals and brain stimulation techniques (see Figures. 1,2).[3,4]

- Theories of Causation and Mental Disorders

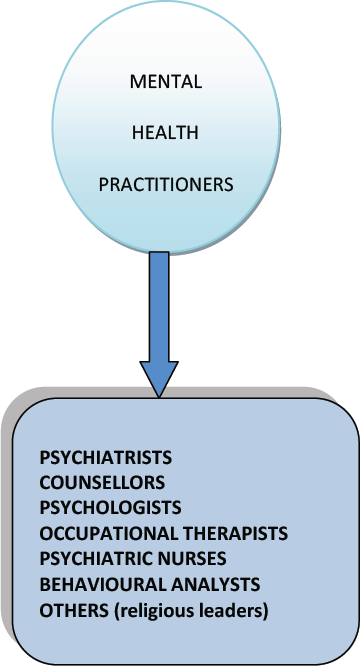

Ongoing disagreements pertaining to causation, classification and treatments of mental disorders are compounded by a diverse range of mental health practitioners who exercise their own brand of diagnosing and treatment in clinics, hospitals, community groups and private practice. While psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric nurses, family doctors, social workers and lay counsellors all perform various types of therapy it is generally only the psychiatrist, family doctor and in some cases, psychiatric nurse who can prescribe medications although this is not clear cut since in some instances psychologists can also prescribe (Fig. 3). Whatever the profession and range of practice, there are serious questions pertaining to empirical evidence of treatment success which is usually defined from the practitioner's point of view

Brain Chemical Imbalance Theory

The most heated controversy within the mental health field centers on the cause of mental disorder. Despite decades of research to prove the chemical imbalance theory a declining number of researchers still endorse it as the causal factor in mental disorder to be treated with pharmaceuticals that target brain chemicals. However, an increasing number of scientists believe that the brain chemical imbalance theory has evolved into a myth that simply helps drug companies sell drugs but has little scientific or medicinal substance. This view is corroborated by a growing number of mental health practitioners and researchers who think that the influence of large pharmaceuticals has resulted in excessive diagnoses, mislabelling, stigma and dangerous and debilitating pharmaceutical side effects. [5]

Most pharmaceuticals currently prescribed as treatments including anti-psychotics, anti-depressants and sedatives were discovered over fifty years ago but their precise effects are still largely unknown. For example, some anti-depressants act on serotonin but there is no definitive proof that a shortage of serotonin is the cause of depression or any other disorder. Moreover, the practice of using a single drug to treat various forms of depression and psychoses (mild to severe) given the current lack of evidence is almost doomed to fail. Verification of this can be found in a meta-analysis of current research that shows that anti-depressant drugs fared minimally better than placebos in clinical trials. Anti-psychotic drugs have been responsible for closing many mental health facilities through control of hallucinations and delusions however social withdrawal, muddled thinking, lethargy and other debilitating side effects have been the result. Hence an increasing number of pharmaceutical manufacturers have noted the lack of treatment success and consequently are rejecting chemical imbalance as an ongoing fruitful endeavour, a view that has resulted in budget cuts, with declining clinical trials and research. [6] Currently, there are other targets emerging in the quest to understand and treat mental disorders. For example, neuro plasticity or the brain's ability to grow new connections has become a keen focus of research interest in the quest to understand and treat mental disorders.

Diagnostic Criteria

Many mental health practitioners and members of the public increasingly consider the Diagnostic Statistical Manual (DSM) as deeply flawed and dangerous primarily because the number of diagnostic criteria has steadily grown to include what were previously considered to be normal behaviors. This has frequently resulted in inappropriate labeling and treatments with powerful medications and side effects that can be worse than the disorder. Papers that report on the effects of pharmaceuticals prescribed for mental disorders often describe ‘modestly superior' efficacy which begs the question as to what definitively does or does not work.[7] Furthermore information in previous versions up to the current DSM V cannot be defined as scientific or medical since research has repeatedly indicated its' validity and reliability as questionable. A case in point refers to maladies that are context specific and can be treated without pharmaceutical intervention including social problems such as poverty, literacy and anxieties (shyness, grief, depression, spirited children). [8,9] Notwithstanding these serious drawbacks, the information in the DSM is still regarded by most practitioners as the final word on who is normal/ abnormal, sane/insane and who can be hospitalized and medicated against his/her will. A different classification of mental health diagnoses is the WHO's International Classification of Disease and Related Health Problems (ICD) (the most recent version is the ICD-11). Although serious problems have been widely acknowledged with both the ICD and DSM, the WHO's diagnostic system is global, multilingual and multidisciplinary and there are different classifications for clinical use, research and primary care.[10]

Self-Limiting Mental Disorders?

Negative life experiences can carry an increased risk of suffering a related mental disorder for some individuals but there are studies that have shown that strength of support (family, community) can mitigate effects and that the majority of people possess enough resiliency to be able to effectively cope.[11,12] There are no sure answers to the duality of resilience versus vulnerability but some possible determinants pertain to beliefs, attitudes, coping strategies, behaviors, psychosocial cohesion. While more research is needed in this area, there are implications for treatment and a need for re-think pertaining to the assumption that all disorder requires treatment without first assessing for coping, resiliency and other existing strengths.[13] A preferred approach for those individuals who are coping might be to indicate where assistance can be obtained if problems with managing daily function should arise in the future.

Implementing Western Mental Health Practice in Developing Countries

There is a concerted effort by global health aid agencies to encourage and support national governments to move toward strengthening sustainable cost effective comprehensive integrated health care systems that includes full equity through universal coverage with strategies to strengthen the system through credible evidence and research.[14] This approach is experiencing varying degrees of success mainly due to a persistent lack of skilled human resources compounded by governance issues as most developing countries struggle with the extreme challenge of finding and retaining trained personnel for those health fields based on known cause, effect and treatments (infectious diseases, nutrition, HIV/AIDs etc.). Given that the Western approach emanates from a different cultural base, is largely biomedical with little emphasis on prevention and promotion, is dominated by conflicting opinions, debates, diagnoses, treatments and uncertain science makes it difficult if not impossible to implement an effective and sustainable program in developing countries that is based on the Western model.[15]

Mental Health System in Uganda

According to Uganda's Health Services Strategic Plan (HSSP), the main challenges in the mental health system include access, a weak referral system (curative, preventive/ promotive), skilled staff shortages and stock-outs of pharmaceuticals. In addition, there is need to extensively strengthen supervision, monitoring and evaluation of existing programs in order to produce timely and useful information pertaining to effectiveness.[16]

The Uganda Ministry of Health (MoH) mandates that there be at least one encoded psychiatric nurse with a 2-year certificate at the outpatient village level and that services at the health centres employ clinical and medical officers however there are many vacancies at both levels. Services at the regional referral hospitals include psychiatric units staffed by psychiatric Clinical Officers (Diploma prepared personnel) while two National referral mental health hospitals staffed by psychiatrists and psychologists offer all mental health services. Private international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) and health facilities that offer mental health services are expensive, are in urban areas and tend to focus on HIV/AIDs thereby limiting access for the majority of individuals requiring assistance.

There is recognition by the Ugandan Government that mental health poses serious public health and development concerns and attempts have and are being made to strengthen the system with some successes pertaining to community awareness, assertive outreach post discharge and increased referral to regional rather than national hospitals. However, an assessment of the mental health policy, legislation, service resources and utilization carried out by the WHO concluded that legislation was outdated and there were major shortcomings in service delivery.[17] In response, the HSSP III focus is on improved efficiency of mental health service delivery through sector strategies and reforms that will combat the identified challenges faced including access, resources, capacity and accountability.

Access and Capacity. The word appropriate emanates from the Latin 'appropriare - ‘to make suitable to time, person and place.'[18] In order to provide appropriate mental health services there has to be an understanding of biology, physiology, psychiatry, psychology and social issues. Ideally, this knowledge would be available through a team consisting of professionals who have acquired the educational and clinical credentials essential to meet the standards of their respective profession (psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric nurses, social workers). Hence, an access to mental health services can be defined as the opportunity and ability to physically obtain and utilize services through interaction with suitable care givers. Capacity denotes the number of professionals who possess the ability, aptitude, competence, and productivity to provide services.

In Uganda, nearly a third of the population live more than five kilometers (3.1 miles) from the nearest health facility, public transportation is limited and if available is unaffordable to most people requiring it. Moreover, mental health services have not yet been fully integrated into the primary health care package so mental health professionals often cannot be found at clinics and appropriate mental health pharmaceuticals are frequently absent. The lack of sufficient qualified mental health personnel has led to task shifting as a solution to meet existing needs i. e., tasks are performed by non-specialist cadres of workers with little or no formal training in mental health including nurses, social workers, community health workers and lay personnel. Findings from studies pertaining to task shifting are mixed. Some studies have concluded that non-specialist health workers are able to alleviate some mental health problems such as depression/anxiety, dementia, maternal depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and alcohol abuse.[19,20] However, other studies that examined interventions carried out by non-specialist health workers concluded that more evidence pertaining to the effectiveness of treatment was needed.[21]

The belief that these workers may provide better care than highly trained professionals due to a common cultural, linguistic and social orientation between the care giver and the recipient may be valid. However, it is important to note that there are 43 different languages/dialects spoken in Uganda and even when interpreters communicate in a similar language and possess similar social backgrounds, there may be significant differences in dialect, values and beliefs. It is frequently difficult for individuals to directly share experiences with care givers around topics pertaining to sex, violence and situations of shame even when linguistic and cultural diversity are bridged. When this information can only be shared through an interpreter or an individual with compromised linguistic skills or different orientations then patient censure or interpretive error will almost certainly occur and a first strike will be made against a successful outcome.[22-24]

A South African study found seriously compromised effective care with adverse outcomes when translators possessed little, if any, knowledge or understanding of psychiatric terminology pertaining to clinical concepts. The structural differences in language/dialects, and local idioms combined with culture-bound values, beliefs, and non-verbal characteristics including head nodding, facial and hand movements, speech impairments, thought disorders, and translation of emotionally loaded nuances can lead to inaccurate assessments, treatments and ultimate outcomes.[25] In sum, patient vulnerability is increased when mental disorder and communication are compromised, a particularly serious problem when this skill is the principal diagnostic and therapeutic treatment tool. The presence of international aid workers with little or no grasp of the language, history and culture can easily result in the creation of two solitudes and inadvertently but seriously impair treatment success.[26]

Governance and Accountability. The Ugandan Government has identified resources that are needed to increase mental health services in Regional Referrals Hospitals and pharmaceuticals in Health Clinics. However, the World Bank reported governance issues that affect the management of development assistance in Uganda specifically that despite rampant absenteeism, spending was largely on salaries. This practice resulted in a loss of financial resources and negatively impacted the basic inputs to provide services. In addition, policies to develop, monitor and evaluate programs largely remain hypothetical and have yet to be translated into practice. Compounding these challenges is Uganda's resentment related to perceived partner attempts to lead and dictate the responsibilities of the MoH, further threatening planned improvements to services which have further threatened solutions to improvement of services. [27]

Gender and Mental Health in Uganda

Surveys in Uganda have documented high rates of gender-based violence in that it has been reported that more than 80% of female clients receiving trauma focused treatments reported at least one sexual assault during their lifetime. In Northern Uganda, in particular, there are many women and children who are survivors of abduction and sexual domestic violence that has resulted in substance abuse and poverty. For example, a recent study to explore mental disorder and its association with sexual risk behaviors and HIV found that more women than men experienced higher rates of depression, psychological distress, alcohol abuse all associated with increased sexual risk behaviors, rape and violence by partners and non-partners. [28] Other findings have indicated that more women in the general population experienced severe mental disorders combined with HIV and admission to hospital. Although these discoveries lend credence to a correlation between trauma and behavior, the lack of crucial information pertaining to whether the disorder preceded or resulted from the traumatic event is crucial in order to reach a thorough understanding and to treat appropriately.[29]

If the risk for mental disorder is gender based, then the differences could be attributed to the hardships that women in Uganda face including poverty, less education, abuse, forced marriages, sex trafficking, fewer job opportunities and for some, restriction in activities outside of the home. However, establishing relationships between these co-morbidities, poverty and mental disorders are inconclusive. Despite pointing to a possible association between common mental disorders and economic deprivation, most women living in poverty do not develop mental illness but simply are at greater risk. Systematic, small-area longitudinal studies in levels of absolute and relative poverty are needed to establish the prevalence and causal associations of disorders. Such studies may help identify the specific factors that are associated with the risk of disorder and resiliency factors that help reduce the risk in persons who face severe economic or social adversity. Whatever the cause(s) of higher female mental dysfunction there is little doubt that the related stigma and shame profoundly disrupts the family and the effects on children place them at risk to develop emotional and behavioral problems. Thus, it has been suggested that the co-morbidities and vulnerability of women need to be addressed through tailored community based programmes which would include social protection and reduce stigmatization.[9]

Lack of Evidence

There is a conspicuous lack of published literature evaluating the implementation of community mental health care in low income sub-African countries. Systems for monitoring and evaluation in Uganda do exist but are challenged primarily by inadequate transport, shortage of skilled human resources, uncoordinated priority setting, lack of a research agenda, and insufficient feedback to the districts.[16]

Despite a great deal of research carried out by several aid agencies with diverse affiliations and foci over the years, it is unfortunate that attempts to improve services for mental disorders have been ineffective due to questionable methodologies, lack of reliable data as well as ideologies and treatments “imported” from another culture. For example, the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview' (CIDI) was hampered by lack of comparability in that risk factors, consequences, patterns and correlates of treatment were not included. Furthermore, a large scale cross-national survey focused on prevalence and not severity; in addition, there was a lack of standardized treatment questions.[12] A recent study carried out by the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) found that research was often outsourced and by ignoring information from staff working ‘on the ground' was too diffuse and not evidence or priority based.[30] Moreover, staff lacked practical experience in the application of findings that were ‘cherry picked' in order to justify decisions about programming to superiors.

Rather than large scale surveys, collecting data that is focussed, accurate, reliable and recent from small, localized studies in order to capture conditions pertaining to cultural content (socioeconomic status, gender, nutrition, literacy, beliefs, treatments, adult, adolescent and child health) is crucial to understanding mental disorders (who, what, where, when and how). Contextual narratives triangulated with quantitative data would elicit appropriate community perceptions, attitudes and behaviours pertaining to mental health not possible with large scale surveys alone. This baseline information can then be monitored longitudinally to reveal unique variables and causal connections on which to draft health policy pertaining to the implementation of appropriate and sustainable programs. Without this information it is difficult to understand the needs of those experiencing mental disorders or put into place effective policy and cost effective budgets. Nonetheless, researchers must be mindful that anecdotal information and sub-standard monitoring and evaluation can sabotage meaningful interpretation, scientific rigor and development projects resulting in costly ineffective planning, implementation and outcomes.[31]

Discussion

Western mental health theory and practice still suffer from much disagreement and conflicting opinions among a diverse range of practitioners pertaining to causes, treatments, and lack of empirical evidence of treatment success. Some information in the DSM are scientifically questionable since they failed to consider context specific and self-limiting behaviors which are related to a social setting and may not require pharmaceutical intervention. Frequent contradictory diagnoses lead to labelling, stigma and serious pharmaceutical side effects. There continues to be ongoing debates about the cultural appropriateness of imposing western ideas with a heavy emphasis on illness and harmful diagnoses and little attention paid to cultural strengths and resilience in assessment, treatment and training of local people. Exporting this model to Uganda with expatriate mentors who lack awareness relevant to local practices, inadequate language skills, and an understanding of the collective spirit and support within communities are areas in which the West still has much to learn. If expatriate mental health practitioners are to partner with Ugandans then there is a need to become culturally literate and embrace cultural humility, discard ideas of superiority that indicate that the Western way is the only way, ensure that assessment is based on needs identified by communities, recognize existing strengths and be humble enough to listen to and accept negative feedback.[32]

There is little doubt that Uganda still faces formidable challenges in the development of an effective and sustainable mental health system, foremost of which is the lack of accessible and qualified practitioners. Task shifting is not a new concept in Uganda and is being carried out within the existing regulatory framework on a continuum from Type I - Type IV and which does include mental health. However, steps to scale-up and strengthen this system are needed and are outlined in recent studies with specific recommendations.[33]

The percentage of nurses in Uganda who are graduates in mental health and work in mental health hospitals far outstrips any other profession (WHO-AIMS Report, Graphs 4.1,4.2). The educational preparation of nurses is an integrated mix of cradle to grave biology, psychology, sociology, pharmacology, curative and public health. Equipped with an understanding of holistic health, nurses can comprehend the important differences between behavioral mental disorders due to difficult life situations and neurological/organic conditions such as epilepsy, HIV/AIDs, dementia etc. Moreover, nurses as nationals are familiar with the culture and dialects in the country and until adequate teams of psychiatrists, psychologists and social workers can be recruited task shifting at all levels could be carried out by nurses with other team members available for consultation as needed.[34-36]

There is a crucial lack of a reliable evidence base on which appropriate country action plans can be based. The impetus to scale up mental health services across Uganda has yet to manifest through published evaluation studies that establish effectiveness of services. However, an opportunity exists to build on experience and establish an evidence base to reveal unique country needs that can be successfully adapted and implemented. Uganda can choose to follow the Western model which emanates from a different cultural base or establish a model based on needs uncovered in small baseline country surveys that will take into account the distinctive cultures, values, gender, and social issues. The establishment of clear definitions to define and identify vulnerability and resiliency in mental disorder will lead to a fuller understanding of the effects of prior life events and result in more appropriate diagnoses and treatment. Behaviors of those who have experienced negative life situations such as poverty, loss, neglect, conflict, individual/family function, abuse and gender related issues must be differentiated from those with neurol ogical/physiological conditions. Moreover, a move away from a purely medical model and toward health promotion and recovery is an important first step that will result in more efficient mental health systems with better services, care and improved outcomes and care to individuals and communities.

Financial Disclosure:

None;

Acknowledgement:

The author gratefully acknowledges Gabriele Marini, Psychotherapist and Project Director of The Center for Victims of Torture/Uganda, for generously sharing his knowledge, experience and perspectives pertaining to the current mental health system in Uganda.

Conflict of Interest:

None

Funding Support:

None

References

- Causes of mental illness. Mayo Clinic Staff Health Information 2013 Available at: http://www.mayoclinic.com/

- [Google Scholar]

- Mental Illness: Is “chemical imbalance” theory a myth? The Toronto Star Newspaper 201318 Oct http://www.thestar.com/news/insight

- [Google Scholar]

- The Book of Woe: The DSM and the Unmaking of Psychiatry. New York: Blue Rider Press: Penguin Group Inc.; 2013.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical Update. DSM: Diagnosing for Status and Money. A Critical Look at the DSM & Economic Forces that Shape It 2014 Available at: http://www.zurinstitute.com

- [Google Scholar]

- Disturbed Minds or Manuals [podcast on the internet] Toronto: The Agenda, TV Ontario 20127 May http://theagenda.tvo.org/

- [Google Scholar]

- Poverty and common mental disorders in developing countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2003;81:609-615.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Toward ICD-11: Improving the Clinical Utility of WHO's International Classification of Mental Disorders. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2010;41(6):457-464.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence, Severity and Unmet Need for Treatment of Mental Disorders: WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;1(21):2581-2590.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post-traumatic stress disorder, resilience and vulnerability. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2007;12:369-375.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lessons learned in developing community mental health care in Africa. World Psychiatry. 2010;9(3):185-189.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Uganda. Ministry of Health. Health Sector Strategic Plan III 2010 2010/11-2014/15

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO and Ministry of Health. In: WHO- AIMS Report on the Mental Health System in Uganda. Kampala; 2006.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health in the Developing World: time for innovative thinking. Spotlight on Tackling Chronic Diseases. Science and Technology for Global Development 2008 July

- [Google Scholar]

- Non-specialist health worker interventions for the care of mental, neurological and substance-abuse disorders in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An overview of Uganda's mental health care system: Results from an assessment using the WHO's assessment instrument for mental health systems (WHO-AIMS) International Journal of Mental Health Systems 2010 Jan 20

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Language, culture, and task shifting - an emerging challenge for global mental health. Global Health Action 2014 Feb 6

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The need for measurable standards in mental health interpreting: a neglected area. The Psychiatric Bulletin. 2012;36:121-124.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The accuracy of interpreting key psychiatric terms by ad hoc interpreters at a South African psychiatric hospital. African Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;16(6)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The Idealist: Jeffery Sachs and the Quest to End Poverty. New York USA: Doubleday: Division of Random House; 2013.

- [Google Scholar]

- HIV prevalence in persons with severe mental illness in Uganda: a cross sectional hospital- based study. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2013;7:20.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Review faults DFID's approach to research evidence. Science and Technology for Global Development 2014

- [Google Scholar]

- (2011). Illogical Framework: The Importance of Monitoring and Evaluation in International Development Studies. 2012 June In: The Cornell Policy Review. 2012;1(1)

- [Google Scholar]

- The key to pursuing higher quality outcomes in acute care hospitals in Low Income Countries. Global Public Health: An International Journal for Research, Policy and Practice 2014 June 1

- [Google Scholar]

- Health Policy Initiative. Futures Group. East, Central and Southern African Health Community (ECSA-HC) Task Shifting in Uganda: A Case Study 2010 Task Order 1

- [Google Scholar]

- Policy Interventions that attract nurses to rural areas: A multicountry discrete choice experiment. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2010;88:350-356.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- and the Mental Health and Poverty Research Program Consortium. A task shifting approach to primary mental health care for adults in South Africa: Human resource requirements and costs for rural settings. Health Policy and Planning. 2011;27(1):42-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]