Translate this page into:

Theory-Driven, Multi-Stage Process to Develop a Culturally-Informed Anti-Stigma Intervention for Pregnant Women Living with HIV in Botswana

* Corresponding author email: op2190@cumc.columbia.edu

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Despite a well-established universal HIV diagnosis and treatment program, Botswana continues to face a high HIV prevalence, in large part due to persistent stigma, which particularly affects pregnant women and interferes with healthcare engagement. Tackling stigma as a fundamental cause of HIV disparities is an important but understudied aspect of current HIV interventions. Our multinational and multicultural team used a theory-driven, multi-stage iterative process to develop measures and interventions to first identify and then target the most culturally-salient aspects of stigma for mothers living with HIV in Botswana. This methodology report examines the stage-by-stage application of the “What Matters Most” (WMM) theory and lessons learned, sharing a replicable template for developing culturally-shaped anti-stigma interventions.

Methods:

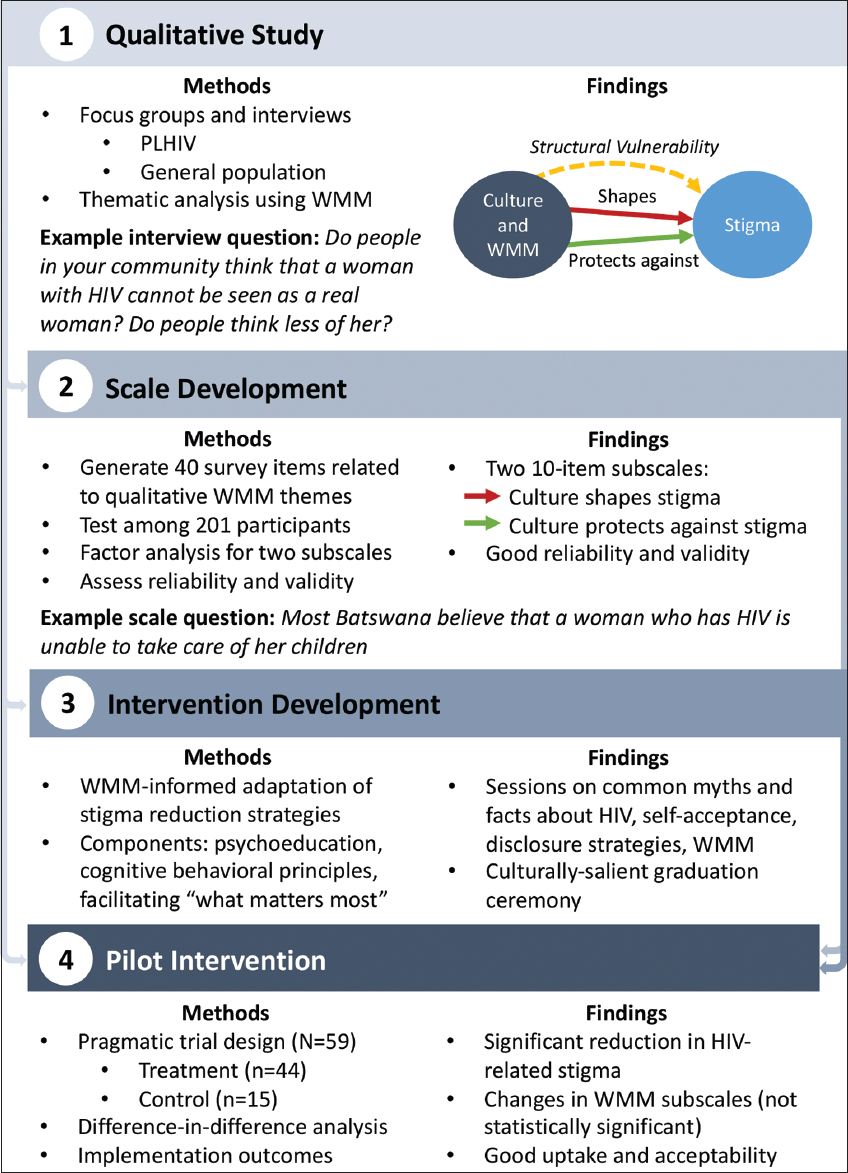

First, we conducted initial qualitative work based on the WMM theory to identify key structural and cultural factors shaping stigma for women living with HIV in Botswana. Second, we developed a psychometrically validated scale measuring how “what matters most” contributes to and protects against stigma for this population. Third, we designed an anti-stigma intervention, “Mothers Moving towards Empowerment” (MME), centered on the local values identified using WMM theory that underly empowerment and motherhood by adapting a cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)-informed, group-based, and peer-co-led anti-stigma intervention specifically for pregnant women living with HIV. Fourth, we conducted a pilot study of MME in which participants were allocated to two trial arms: intervention or treatment-as-usual control.

Results:

Our qualitative research identified that bearing and caring for children are capabilities essential to the concept of respected womanhood, which can be threatened by a real or perceived HIV diagnosis. These values informed the development and validation of a scale to measure these culturally-salient aspects of stigma for women living with HIV in Botswana. These findings further informed our intervention adaptation and pilot evaluation, in which the intervention group showed significant decreases in HIV stigma and depressive symptoms compared to the control group. Participants reported overcoming reluctance to disclose their HIV status to family, leading to improved social support.

Conclusion and Global Health Implications:

Previous studies have not utilized culturally-based approaches to assess, resist, and intervene with HIV-related stigma. By applying WMM in each stage, we identified cultural and gendered differences that enabled participants to resist HIV stigma. Focusing on these capabilities that enable full personhood, we developed an effective culturally-tailored anti-stigma intervention for pregnant women living with HIV in Botswana. This theory-driven, multi-stage approach can be replicated to achieve stigma reduction for other outcomes, populations, and contexts.

Keywords

HIV

Stigma

Culture

Matrescence

Intervention

Botswana

Qualitative Methods

Theory

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

1. Introduction

Botswana has the third-highest rate of HIV in the world1 and has served as a model for HIV response as the first sub-Saharan country to offer universal treatment. However, treatment uptake remains limited by HIV-related stigma.2 Despite the numerous biomedical advancements for HIV/AIDS, psychosocial impediments continue to deter the progress towards ending the epidemic, with stigma remaining a particularly pervasive barrier.3,4 Unfortunately, few efforts have directly targeted stigma itself in order to appropriately include resistance and reduction techniques in HIV-related interventions.5–8 It was, therefore, necessary to examine and develop methods to address HIV-related stigma in Botswana9 to facilitate the design and implementation of stigma mitigation and reduction interventions.

We began our work in Botswana with a formative qualitative study investigating cultural factors shaping stigma, based on the “What Matters Most (WMM)” theory.10 WMM enables the identification of the mechanisms by which stigma operates within a particular cultural setting. The theory proposes that stigma is felt most acutely when participation in activities integral to full “personhood” (e.g., being a valued and respected individual) within a local context is threatened.10 Further, WMM identifies how the inability to take part in locally valued and respected activities (e.g., status, work, family) shapes stigma, which allows for assessment and subsequent intervention.11,12

In addition to grounding our stigma work in Botswana in WMM, we developed a multi-stage process to not only elucidate HIV stigma but also, of equal importance, measure it and intervene to address it. To date, few anti-stigma interventions in low-resource settings have incorporated cultural aspects into their design.13 We posit that using the WMM theory provides a systematic approach to incorporating culture into anti-stigma efforts14 and this project demonstrates its application with intervention design and dissemination.

1.1. Objectives

This Methodology Article examines the stage-by-stage application of WMM and lessons learned that can be informative for developing culturally-focused anti-stigma interventions. Specifically, an overview of the inter-linked process for each of the following studies is discussed:

1) Qualitative Study: identifying WMM for men and women in Botswana and examining how the fulfillment of these goals is shaped by HIV and structural vulnerability in Botswana15,16

2) Scale Development: developing and psychometrically validating a scale measuring HIV stigma based on WMM for women in Botswana8

3) Intervention Development: conceptualizing and designing a group-based anti-stigma intervention based on WMM for pregnant women living with HIV in Botswana14

4) Pilot Intervention: assessing the effectiveness of a pilot intervention based on WMM for reducing HIV-related stigma among pregnant women living with HIV in Botswana 7

2. Methods

A detailed discussion of the methods for each of the four component studies is available elsewhere.7,8,14–16 Here, we describe key elements of each study’s methods to provide an overview of the overall process across the studies. Applying WMM enabled a theory-driven, four-stage process: 1) initial qualitative work, generating results to inform; 2) development and validation of an HIV stigma scale capturing participant-identified, culturally-salient norms that contribute to and enable resistance to stigma. These insights and scale were then taken to the 3) adaptation of a stigma intervention co-led by a clinician and peer for pregnant women with HIV and 4) pilot evaluation of the intervention’s effectiveness in reducing stigma and improving mental health (Figure 1). Across Stages 1-3, the use of WMM is prominent in assessing how HIV-related stigma operates in this context, measuring HIV-related stigma in a way that incorporates culturally-salient elements, and developing the specifics of the resulting intervention sessions. Culminating from these three stages is the pilot evaluation of a culturally-informed anti-stigma intervention.

- Theory-Driven 4-Stage Process Diagram

2.1. Qualitative Study

In 2017 we recruited persons living with HIV (PLHIV) and community members (HIV status not asked for five focus groups (N=38) and 46 in-depth interviews to explore how HIV stigma manifested and to understand HIV stigma from both those who may experience and perpetuate it. WMM theory informed the development of the interview guides to capture salient sociocultural aspects of HIV-related stigma and how HIV-related stigma influenced health-related behavior and outcomes. Additionally, we convened clinicians with long-term clinical/policy experience addressing HIV/AIDS in Botswana to contextualize the results.16

2.2. Scale Development and Psychometrics

Using WMM theory, we operationalized themes from our qualitative data about what makes someone a “respected woman” in Botswana into survey items (e.g., “Most Batswana respect a woman with HIV who raises successful children”). Key concepts included religion, being a mother, and being a supportive wife. Local clinicians reviewed preliminary items for content validity, resulting in 40 items administered to 201 participants. Factor analysis was used to assess the two subscales, which focused on cultural aspects that shape or protect against HIV stigma. Reliability was assessed via internal consistency and test-retest reliability. Construct validity was assessed by comparison with previously validated measures of HIV stigma and related psychosocial outcomes (e.g., depression, social support).8

2.3. Intervention Adaptation

Our intervention incorporated evidence-based stigma reduction strategies for reducing the internalized stigma associated with HIV, including psychoeducation, challenging stereotypes, and identifying coping strategies in response to stigma. The intervention was co-led by a local mental health clinician and a peer (i.e., a woman living with HIV who was currently a mother). Further, elements of the proposed intervention incorporated WMM for women in Botswana, which was derived from our formative qualitative work. A multisectoral, multicultural team adapted the intervention based on a prior anti-stigma intervention for mental illness that also incorporated WMM; it was then revised by local clinicians and by women living with HIV who had experienced pregnancy, many of whom were subsequently trained to deliver the intervention.7,14 Therefore, the evidence-based stigma reduction techniques combined with core cultural elements integral for women to thrive while living with HIV allowed for a culturally-informed anti-stigma intervention. We named the intervention “Mothers Moving towards Empowerment” (MME), with the acronym also being the Setswana term Mme, which connotes respect for a woman.14

2.4. Pilot Evaluation

A pilot pragmatic trial to evaluate uptake, acceptability, and efficacy was conducted. Participants were allocated to two trial arms: intervention or treatment-as-usual control. Participants completed measures assessing stigma (including the newly developed WMM-based scale) and related psychosocial outcomes (e.g., depression) at baseline, post-intervention, and 4-months postpartum. An intention-to-treat, difference-in-difference analysis was used to compare changes in outcomes between those allocated to the intervention group versus the control group.7

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative Study

Our findings from the formative qualitative study showed that ‘being a respected mother’ was an indicator of respected womanhood among Batswana women. This indicator was threatened by real or perceived HIV-positive status. Critical among these results were participant responses that emphasized the need to have children, take care of children, look after themselves and their families, and get married. There was also a gendered structural vulnerability that emerged that informed women living with HIV who experienced pregnancy. Women were typically tested first for HIV through antenatal care (i.e., as part of national efforts to prevent HIV transmission from mother to child), resulting in the blame for bringing HIV into relationships. This gendered inequality resulted from well-intended policies focused on providing women quality antenatal care, yet resulted in a disproportionate amount of stigma experienced by these women.16

3.2. Scale Development

The qualitative results informed the development and validation of a culturally-based scale to measure perceived HIV-related stigma among women in Botswana. Factor analysis of the proposed items resulted in two 10-item subscales representing cultural factors shaping and protecting against stigma, which showed good initial reliability and construct validity with established measures. The How Culture Protects subscale innovatively measures capabilities associated with stigma resistance that may facilitate social reintegration and empowerment while facing multiple vulnerabilities. The items demonstrate the protective cultural values that women can fulfill to lessen HIV-related stigma, informing the basis of our subsequent anti-stigma intervention.8

3.3. Intervention Development

In order to empower women to resist HIV-related stigma, we adopted a cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)-informed, group-based, and peer-co-led stigma intervention (i.e., MME) specifically for pregnant women living with HIV. The intervention aimed to address self-stigma by restructuring negative cognitions and supporting women in fulfilling participant-identified cultural norms of a “respected mother,” over eight weekly 90-minute sessions took place. Themes of being a respected mother were interwoven throughout all sessions, and; furthermore, session 8 solely focused on WMM-based themes about being a respected mother as a woman living with HIV and emphasized the cultural components that protect against stigma that stemmed from the formative qualitative research. Two bilingual co-leaders (a clinician and a peer mother with HIV) led the intervention in English, with elaborations in Setswana. Although English is Botswana’s official language, many individuals primarily speak Setswana, and key Setswana terms have no English equivalents. This innovation in translation may improve the cultural impact of MME by maximizing the meaning of local terminology. All participants would receive a certificate of graduation if they completed at least 5 sessions. Additionally, to symbolize the achievement of WMM, the intervention culminated in a graduation ceremony, in which mothers were given a tjale, a traditional shawl typically given to a woman by in-laws to signify her upgraded status as a wife/woman.14

3.4. Pilot Evaluation

The pragmatic trial design allocated participants to the intervention (N=44) or treatment-as-usual control (N=15). Results indicated moderate uptake, good acceptability, and preliminary effectiveness for the MME intervention. Although attrition remained a challenge, it is suggestive that our intervention itself was not the challenge. Participants cited various obstacles, such as relocation for postpartum confinement (a common local practice) and work; overall feedback from participants indicated a positive reception towards the intervention. The intervention resonated with participants by challenging negative perceived and internalized stigmatizing beliefs. Participants found discussions around motherhood in the context of HIV insightful. The peer co-leader provided valuable anecdotal experience and inspiration, providing examples of how she resisted stigma while fulfilling her roles as a mother and woman. Participants reported overcoming reluctance to disclose their HIV status to family, leading to improved social support qualitatively.7

Quantitatively, an intent-to-treat difference-in-difference analysis showed significant decreases in HIV-related stigma and depressive symptoms at four-months postpartum compared with concurrent changes in these outcomes in the control group that were sizeable in nature (Cohen’s d = 1.0 or greater). Further, while not statistically significant, our intervention also showed moderate effect size changes in expected directions for the two WMM subscales from our HIV-related stigma scale, which may point to the intervention’s effectiveness in targeting culturally-salient aspects of HIV stigma in the context of Botswana.7

4. Discussion

Previous studies have not utilized culturally-based approaches to assess, resist, and intervene against HIV-related stigma.13,14 By applying WMM in each research stage, we identified cultural and gendered differences that enabled participants to resist HIV stigma. We engaged both men and women with and without HIV for the qualitative study. Having multiple perspectives on how HIV-related stigma affects different individuals allowed for confirmation of findings and strengthened our understanding of the unique vulnerabilities of pregnant women. This was further informed by our inclusion of local cultural experts in all stages of analysis. The results formed the foundation for developing a WMM-based stigma scale to capture the extent to which perceived cultural norms both shape stigma and enable stigma resistance among women. The measurement will allow further understanding of how stigma operates locally by providing a means of quantifying stigma over time and its association with maternal and child health outcomes.

We grounded our stigma scale in concepts identified by women as most valued locally rather than in universal concepts. Further, most existing HIV-related stigma scales focus on harmful aspects of stigma (e.g., shame, guilt, isolation). Despite the acknowledged importance of assessing resilience among PLHIV, measurement of how HIV-related stigma can be resisted remains an underdeveloped area of study.17 The WMM theory allows us to measure not only the extent to which stigma impacts women living with HIV in culturally-salient ways but also the extent to which stigma can be resisted by engaging in culturally valued activities.

Our process of adapting the intervention content to address WMM to women in Botswana addresses the specific needs of participants. Additionally, the intervention promoted selective disclosure of HIV status to trusted family and friends, aiming to enhance social support, improve HIV treatment adherence, and mitigate depressive symptoms. Finally, the conferring of tjales at graduation can symbolize the transformation from stigmatization to empowerment as a valued, respected woman.

Pilot findings indicate good acceptability among participants, with resoundingly positive feedback and improved stigma and depression scores. Women used both the specific techniques and a sense of empowerment to directly overcome stigma-related fears, such as disclosing their HIV-positive status to close others, with lasting effects into the postpartum period. Future studies can investigate long-term effects on HIV treatment adherence and child health outcomes.

To scale up this intervention in the future, we propose to integrate the intervention into antenatal services. Pragmatically, this will help address recruitment and attrition by incorporating the intervention into existing perinatal responsibilities. Theoretically, it also advances the WMM framework by structurally integrating the concept that actively resisting stigma is part of ‘being a respected mother’ to promote the baby’s health during routine antenatal care alongside other health-promoting activities.

4.1. Limitations

This multi-stage methodology paper must be considered in light of several limitations. First, we acknowledge that this process is very time and labor-intensive. While we strive for this process to be informative for other studies focused on stigma reduction, we understand that the resources that this requires may not be realistic across settings and collaborations. Second, this process required a multinational, multicultural team to adequately address and integrate the stigma reduction field with the culturally various aspects that emerged throughout the four stages that ultimately allowed us to develop and pilot test our intervention. Third, moving from one stage to the next in terms of elucidating how stigma operates in a setting, developing measures to properly have a standardized measure to be used for stigma, and then incorporating these elements into intervention design and evaluation also requires a dedicated and sustained team to ensure an iterative process that advances from each stage to the next.

4.2. Implications

Notwithstanding the limitations, we believe there are countervailing strengths of our multi-stage process for the study of stigma and intervention implementation. Our process demonstrates effective mechanisms for addressing the intractable challenge of the stigma that persists even in the presence of such a strong HIV treatment infrastructure. Additionally, despite multiple steps, by sequentially systemizing our process, it can be repeated in the future or in different places, with different populations, or with different outcomes. Further, we hope that by showcasing the various studies that emerged from our formative qualitative research, especially that of the development of culturally tailored stigma measures and their application with an associated stigma intervention, we show how necessary it is to develop methods that incorporate elements of culture into addressing stigma.13,14

We focused on pregnant women living with HIV as our initial formative women showed stigma to be most acutely felt in this population. However, we are now in the process of engaging in the same multi-stage process for men living with HIV in Botswana, further supporting the idea that our process is flexible and replicable. As such, our process demonstrates clear steps for giving credence to culture as a powerful element of stigma and for developing measures and tailoring interventions to assess and reduce stigma. We believe this process can be for various populations and needs, thus better capturing and addressing how stigma impacts populations’ health outcomes in the pursuit of long-term and sustainable improvements.

5. Conclusion and Global Health Implications

A theory-driven, multi-stage iterative process stemming from formative qualitative results was integral to developing a stigma intervention for pregnant women living with HIV in Botswana. We demonstrate a replicable process for developing culturally informed interventions. Participants expressed that the cultural salience of the intervention addresses their needs, suggesting good acceptability. By basing the intervention on qualitative findings and having all stages driven by a theoretical framework of culturally-salient aspects of stigma, we identified aspects that are plausible barriers to adherence as well as how stigma can be resisted by engaging in culturally valued activities. We then developed, with the leadership of our cultural experts, an effective culturally-tailored intervention to address the vulnerability and stigma that women living with HIV face. We plan to scale up our intervention nationwide and continue to refine our efforts to address cultural aspects most important to women. We also believe this multi-stage approach can be replicated to achieve stigma reduction for other outcomes, populations, and contexts.

Acknowledgments:

We wish to thank Evan Eschliman for providing early feedback on the initial design and finalized design for the figure used in this paper for this project.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial disclosures to report.

Funding: This research was supported by a grant and core support services from the Penn Mental Health AIDS Research Center (PMHARC), an NIH-funded program (P30MH097488), the Focus for Health Foundation, and the Penn Center for Global Health. The study also benefited from core support services provided by the Penn Center for AIDS Research, an NIH-funded program (P30AI045008). The writing of this manuscript was also supported by Fogarty NIH Grant to Dr. Yang, PI (R21 TW 011084-01). Ohemaa Poku was supported by the T32 Global Mental Health Training Program at the Bloomberg School of Public Health, Department of Mental Health (5T32MH103210-05; PI: Judith Bass).

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the ethics committees of the University of Botswana, the Botswana Ministry of Health, Princess Marina Hospital, University of Pennsylvania, New York University, and the Greater Gaborone District Health Management Team. The University of Botswana IRB (REF: UBR/RES/IRB/BIO/093, approved 2018-10-05), the Ministry of Health and Wellness’ Health Research and Development Committee of Botswana (HRDC) IRB (REF: HPDME:13/18/1, approved 2018-10-15), the Princess Marina Hospital IRB (REF: 5/79(456-1-2018), approved 2018-11-13), University of Pennsylvania IRB (REF: 829913, approved 2018-06-28), New York University IRB (REF: IRB-FY2018-1967, approved 2018-07-30); and the Greater Gaborone District Health Management Team (GG-DHMT, approved 2018-10-23).

Disclaimer: None.

References

- National Datasheets:People Living with HIV. AIDSinfo. Published August 11, 2020 https: //aidsinfo.unaids.org/

- [Google Scholar]

- Botswana's HIV response:policies, context, and future directions. J Community Psychol. 2020;48(3):1066-1070. doi:10.1002/jcop.22316

- [Google Scholar]

- Stigma reduction:an essential ingredient to ending AIDS by 2030. italic> Lancet HIV. 2021;8(2):e106-e113. doi:10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30309-X

- [Google Scholar]

- Falling short of the first 90:HIV stigma and HIV testing research in the 90-90-90 era. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(2):357-362. doi:10.1007/s10461-019-02771-7

- [Google Scholar]

- Stereotype content model explains prejudice for an envied outgroup:scale of anti-Asian American Stereotypes. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2005;31(1):34-47. doi:10.1177/0146167204271320

- [Google Scholar]

- Stigma reduction interventions in people living with HIV to improve health-related quality of life. Lancet HIV. 2020;7(2):e129-e140. doi:10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30343-1

- [Google Scholar]

- A pilot pragmatic trial of a “what matters most”-based intervention targeting intersectional stigma related to being pregnant and living with HIV in Botswana. AIDS Res Ther. 2022;19(1):26. doi:10.1186/s12981-022-00454-3

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychometric validation of a scale to assess culturally-salient aspects of HIV stigma among women living with HIV in Botswana:engaging “what matters most”to resist stigma. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(2):459-474. doi:10.1007/s10461-020-03012-y

- [Google Scholar]

- Reflections on Qualitatively Investigating HIV and Mental Illness Stigma in Botswana with a Multicultural and Multinational Team. SAGE Publications Ltd 2020 doi:10.4135/9781529742961

- [Google Scholar]

- Culture and stigma:adding moral experience to stigma theory. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(7):1524-1535. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.013

- [Google Scholar]

- “What matters most:”a cultural mechanism moderating structural vulnerability and moral experience of mental illness stigma. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:84-93. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.009

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of China-to-US immigration on structural and cultural determinants of HIV-related stigma:implications for HIV care of Chinese immigrants. Ethn Health. 2022;27(3):509-528. doi:10.1080/13557858.2020.1791316

- [Google Scholar]

- Including culture in programs to reduce stigma toward people with mental disorders in low- and middle-income countries. Transcult Psychiatry. 2020;57(1):140-160. doi:10.1177/1363461519890964

- [Google Scholar]

- 'Mothers moving towards empowerment'intervention to reduce stigma and improve treatment adherence in pregnant women living with HIV in Botswana:study protocol for a pragmatic clinical trial. Trials. 2020;21(1):832. doi:10.1186/s13063-020-04676-6

- [Google Scholar]

- Identifying “what matters most”to men in botswana to promote resistance to HIV-related stigma. Qual Health Res. 2021;31(9):1680-1696. doi:10.1177/10497323211001361

- [Google Scholar]

- Stigma, structural vulnerability, and “what matters most”among women living with HIV in Botswana, 2017. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(7):1309-1317. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2021.306274

- [Google Scholar]

- The people living with HIV (PLHIV) resilience scale:development and validation in three countries in the context of the PLHIV stigma index. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(2):172-182. doi:10.1007/s10461-019-02594-6

- [Google Scholar]