Translate this page into:

Thirty Years of United Nations Inter-Agency Working Group’s Global, Regional, and National Maternal Mortality Estimates Revisited

*Corresponding author: Yifru Berhan, MD, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, St Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Tel: +251911405812 yifruberhanm@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Berhan Y, Abeba S. Thirty years of united nations inter-agency working group’s global, regional, and national maternal mortality estimates revisited. Int J Matern Child Health AIDS. 2024;13:e004. doi: 10.25259/IJMA_679

Abstract

Over the last three decades, the United Nations interagency working group series of model-based maternal mortality estimation showed a significant reduction in maternal mortality ratio (MMR) at global, regional, and national levels. However, the contribution of sub-Saharan Africa for the global maternal deaths in 2020 was nearly two-fold higher than before, and the top five countries with high burden of maternal deaths remained unchanged after four decades. In this commentary, we argue that not all countries with high maternal deaths had high MMR; the lower MMR was noted as shadowing the large number of maternal deaths in countries with high rates of total births. We critically appraised the changes and challenges in maternal mortality measurements. We recommend the use of multiple indicators and categorizing the absolute number of maternal deaths to assess individual countries’ maternal health status. As the majority of maternal deaths are preventable and all maternal deaths are catastrophic to the family, estimating the absolute number of maternal deaths should be given equal weight in future research undertakings.

Keywords

Maternal Mortality

Maternal Health

Maternal Mortality Rate

United Nations

Sub-Saharan Africa

Health Status

Maternal mortality measurement is one of the most challenging statistical parameters in health status assessment. This is particularly important in low-income countries where quite a large number of mothers do not utilize the continuum of maternity care. Adding to the challenges, there is no established civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS), and resources are scarce and conditions unfavorable to conduct community-based representative maternal mortality studies or census.[1,2] To fill this gap, the United Nations inter-agency working group (IAWG) has been producing a series of model-based global, regional, and country-level maternal mortality estimates pioneered by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1983. Thereafter, the series was later joined by United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) in 1996, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) in 2001, the World Bank and United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA)/Population Division in 2006.[2–6]

According to IAWG 2020 estimation, the global number of maternal deaths and maternal mortality ratio (MMR) declined by 46% and 42%, respectively (from 532,000 and 400/100,000 live births [LB] in 1990 to 287,000 and 223/100,000 LB in 2020).[3,4,6] The decline was credited more to the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) era. Notably, the first five years of the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) era (2016–2020) was assessed as a period of stagnation with annual rate of MMR global decline by −0.04% as compared to 2.7% of the MDG era (2000–2015) and 2.1% of the whole period (2000–2020).[6] Most importantly, the current pace of annual rate of MMR reduction is too slow to achieve the SDG global target goal of less than <70/100,000 LB. This requires 11.6% annual reduction in the 10-year period.

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and South Asia continued shouldering the largest number of maternal deaths at regional level. This witnessed reduction in the SSA maternal deaths; and ending preventable maternal deaths (EPMD), to the level Western countries achieved before 1940. However, bringing about global convergence is probably a long way to go. SSA contribution to the global maternal deaths nearly doubled in three decades: 219,000/585,000 (37%) in 1990, 247,000/529,000 (47%) in 2000, 201,000/303,000 (67%) in 2015, and 206,000/287,000 (71%) in 2020.[3–6] The MMR of SSA declined by 34%, wherein the trend was going down, but the proportion of maternal deaths contributing to global maternal deaths was going up. Bottom line, one looked like a mirror reflection of the other [Figure 1].

- (panel 1) Sub-Saharan African contribution to the global maternal deaths, (panel 2) total maternal deaths, (panel 3) and the trend of maternal mortality ratio/1,00,000 live births, 1990–2020.

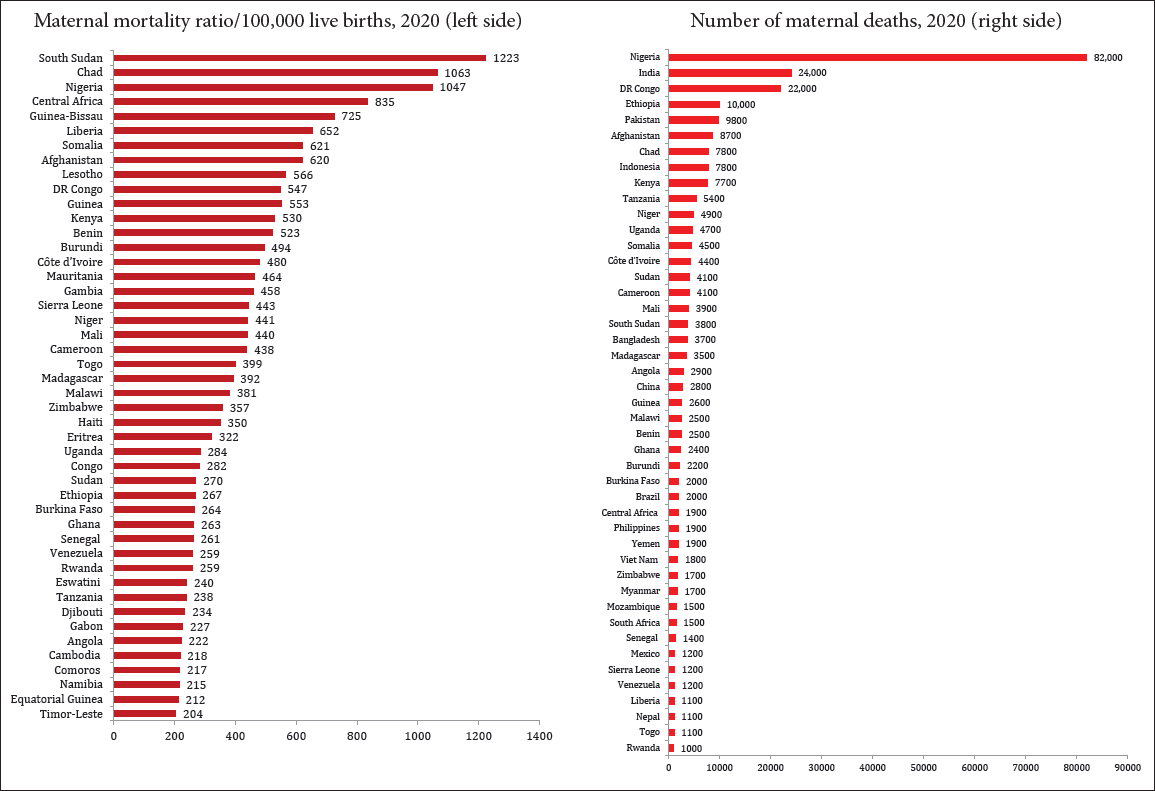

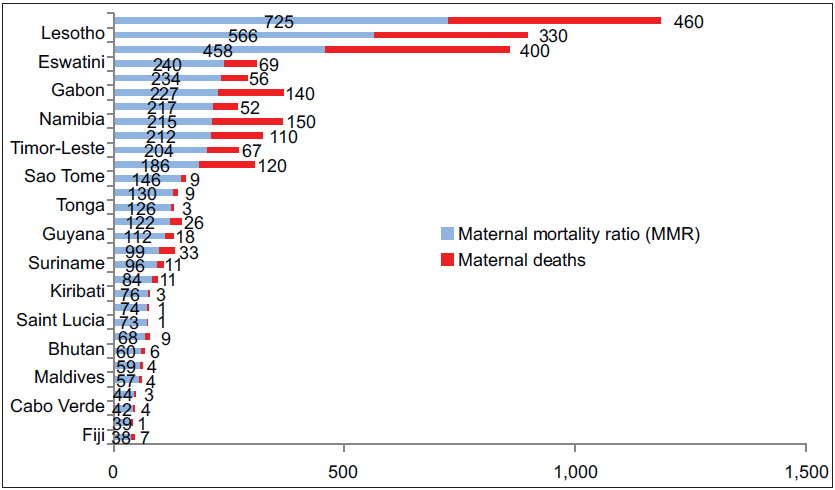

Exceptionally, in countries with large annual births and a large number of maternal deaths, the reduction in MMR did not look accompanying by a relative reduction in absolute number of maternal deaths that was merely due to a large denominator. As shown in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 1, in SSA and some other countries, despite a high number of maternal deaths, their MMRs appeared lower than in small population-sized countries. In countries with relatively low birth rates, a few number of maternal deaths (but higher for their population) largely inflated the MMRs.

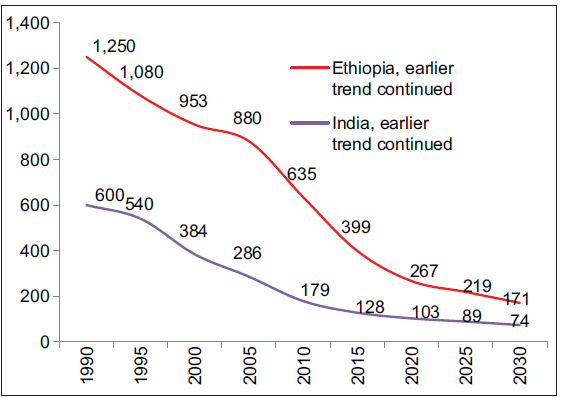

In Ethiopia for example, the MMR declined by 79% from 1,250 in 1990 and by 73% from 953 in 2000 to 267 in 2020/100,000 live births (LB),[2,6,7] [Figure 2], which made this country in the moderate MMR category (100–299/100,000 LB). Its MMR was also less than half of the SSA average for 2020 (545/100,000 LB). However, the maternal deaths of Ethiopia (10,000) were among the highest in the world from a single country, fourth to Nigeria, India, and Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The MMRs of South Sudan and Chad were globally at the top (extremely high), and each was almost four-fold higher than Ethiopia’s MMR, but the number of maternal deaths in South Sudan and Chad was estimated at 3,800 and 7,800, respectively. The equivalent analysis for South Sudan and Chad, however, showed that the number of maternal deaths could have been 47,000 and 40,000, respectively, provided they had the population size of Ethiopia.

- The trend of maternal mortality ratio in India and Ethiopia (1990–2020) and projections to 2025 and 2030.

Similarly, many low-income countries with small population sizes have a low number of maternal deaths, while their MMR was among the highest in the world. Fourteen countries included in the top 46 by their MMRs were excluded from the top 45 countries with high maternal deaths, and another 14 countries with a large population size and lower MMR were included in the top 30 group with highest number of maternal deaths [Supplementary Figure 2 left side - Maternal Mortality Ratio and right side - Number of Maternal Deaths].[6]

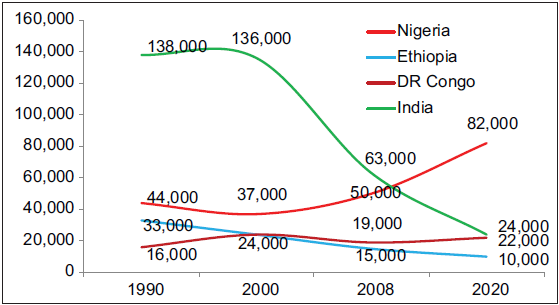

In 2020, India, Pakistan, and Indonesia were among the top 10 countries contributing to 65% of maternal deaths worldwide, with their MMRs were 103, 154, and 173/100,000 LB, respectively. The absolute number of maternal deaths in India was the second highest, but declined by 83% (from 138,000 and 600/100,000 LB in 1990–24,000 and 103/100,000 LB in 2020) [Figure 3].[5,6] The multiplication factor for the maternal deaths to LB ratio being 100,000 had inflated the MMR of countries with relatively lower annual births [Supplementary Figure 3].

- The trend of maternal deaths in historically major contributor countries for the global maternal deaths (1990–2020), DR: Democratic Republic (DR) of the Congo.

Among the four countries historically with high maternal deaths (India, Nigeria, DRC, and Ethiopia), a significant reduction in both MMR and maternal deaths was observed in Ethiopia (two-fold) and in India (three-fold). Ethiopia and India accounted for about 6% and 25% of global maternal deaths in 1990, and in 2020 their contribution was 3% and 8%, respectively. To the contrary, the maternal deaths estimated for Nigeria in 2020 was almost two-fold higher than the 1990 estimate, and 50% increment was as well noted in DRC [Figure 3].[4-6,8]

Ten countries (Nigeria, India, DRC, Ethiopia, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Indonesia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda) had continued being on the top list, contributing to more than two-third of maternal deaths globally. Virtually, there was no change in the top five countries after two decades [Supplementary Figure 4]. Between 1980 and 2008, out of 181 countries, six countries (India, Nigeria, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Ethiopia, and DRC) contributed to 50% of global maternal deaths, and all were suffering from protracted conflicts.[9] The contribution of these six countries was again 51% (267,000/529,000) in 2000 and 55% (156,500/287,000) in 2020,[3,6] indicating that the majority (two-thirds) of mothers died in a couple of countries all the way from 1990 to 2020, but their MMRs became low (20–99) to moderate (100–299) range with time. As an example, the MMRs of India and Ethiopia showed dramatic decline (ranking 67th and 31st from the worst to the lowest) and their maternal deaths reduced by 83% and 70%, respectively. Nevertheless the number of maternal deaths in each country was still in the category of global record (extremely high).

Worryingly, the MMR and absolute number may not pass a similar message for policy makers. The relatively lower MMR in countries with a large population and large number of maternal deaths may open room for complacency, low resource mobilization, and less political commitment. As the majority of maternal deaths are preventable and every maternal death is catastrophic to the family, should the absolute number not be given more weight than estimating the ratio against the total births for future communication? In other words, may the lower MMR shadow the actual magnitude of the problem in countries with large population sizes and large maternal deaths? More than that, should maternal deaths be measured by MMR or be counted as maternal death surveillance and response?

Until consensus is reached, it is probably judicious to use multiple indicators including MMR, maternal mortality rate, absolute maternal deaths, and/or measuring severe maternal outcome (maternal near-misses and maternal deaths) to assess the progress, instead of hovering only the MMR. Categorizing individual countries by the number of maternal deaths, may as well avoid possible complacency in countries with high number of maternal deaths and relatively lower MMR. We proposed the following category of maternal deaths, somehow consistent with terminologies used for MMR category:[5] Very low (<100), low (100–499), moderate (500–999), high (1,000–4,999), very high (5,000–9,999), and extremely high (10,000+) maternal deaths [Supplementary Table 1].

As a limitation, due to changes in data availability and modifications in methodology, the model-based global, regional, and country-based estimations at different times showed variation in MMR estimates. Further, the model-based estimation cannot substitute primary national survey findings.

In conclusion, global maternal deaths have declined by nearly half over three decades. However, the top five countries with a high burden of maternal deaths remained unchanged. In the same period, the SSA MMR declined by 34%, but its contribution to the global maternal deaths has increased by nearly two-fold. The lower MMR was noted shadowing the large number of maternal deaths in countries with high rate of total births. We question the strength of MMR as maternal death measurement for policy development. Therefore, to give more weight to the best maternal mortality measurement, MMR needs further investigation and reaching global consensus.

SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE

| Country | Total births | Reported maternal deaths | Maternal mortality ratio | Maternal deaths category |

| Nigeria | 8,003,000 | 82,000 | 1047 | Extremely high (10,000+) |

| India | 23,056,000 | 24,000 | 103 | |

| DR Congo | 4,134,000 | 22,000 | 547 | |

| Ethiopia | 3,928,000 | 10,000 | 267 | |

| Pakistan | 6,425,000 | 9,800 | 154 | Very high (5,000–9,999) |

| Afghanistan | 1,447,000 | 8,700 | 620 | |

| Indonesia | 4,462,000 | 7,800 | 173 | |

| Chad | 766,000 | 7,800 | 1063 | |

| Kenya | 1,488,000 | 7,700 | 530 | |

| Tanzania | 2,347,000 | 5,400 | 238 | |

| Niger | 1,181,000 | 4,900 | 441 | High (1,000–4,999) |

| Somalia | 719,000 | 4,500 | 621 | |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 943,000 | 4,400 | 480 | |

| Cameroon | 959,000 | 4,100 | 438 | |

| Sudan | 1,548,000 | 4,100 | 270 | |

| Mali | 932,000 | 3,900 | 440 | |

| South Sudan | 315,000 | 3,800 | 1233 | |

| Bangladesh | 2,995,000 | 3,700 | 123 | |

| Madagascar | 906,000 | 3,500 | 392 | |

| Angola | 1,360,000 | 2,900 | 222 | |

| China | 10,758,000 | 2,800 | 23 | |

| Guinea | 469,000 | 2,600 | 553 | |

| Benin | 482,000 | 2,500 | 523 | |

| Malawi | 666,000 | 2,500 | 381 | |

| Ghana | 907,000 | 2,400 | 263 | |

| Burundi | 440,000 | 2,200 | 494 | |

| Burkina Faso | 793,000 | 2,000 | 264 | |

| Brazil | 2,723,000 | 2,000 | 72 | |

| Central Africa | 237000 | 1,900 | 835 | |

| Philippines | 2,499,000 | 1,900 | 78 | |

| Myanmar | 912,000 | 1,700 | 179 | |

| Zimbabwe | 491,000 | 1,700 | 357 | |

| South Africa | 1,156,000 | 1,500 | 127 | |

| Mozambique | 1,191,000 | 1,500 | 127 | |

| Senegal | 556,000 | 1,400 | 261 | |

| Sierra Leone | 265,000 | 1,200 | 443 | |

| Venezuela | 438,000 | 1,200 | 259 | |

| Mexico | 1,866,000 | 1,200 | 59 | |

| Liberia | 164,000 | 1,100 | 652 | |

| Togo | 279,000 | 1,100 | 399 | |

| Nepal | 617,000 | 1,100 | 174 | |

| Rwanda | 406,000 | 1,000 | 259 | |

| Haiti | 269,000 | 950 | 350 | Moderate (500–999) |

| Iraq | 1,203,000 | 900 | 76 | |

| Zambia | 683,000 | 890 | 135 | |

| Algeria | 924,000 | 760 | 78 | |

| Cambodia | 318,000 | 710 | 218 | |

| Mauritania | 156,000 | 700 | 464 | |

| Colombia | 723,000 | 550 | 75 | |

| Congo | 180,000 | 500 | 282 | |

| Other countries with low and very low maternal deaths | Variable | 100–499 | Variable | Low (100–499) |

| Variable | <100 | Variable | Very low (<100) |

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURES

- Top 46 countries (left side) with maternal mortality ratios of above 200/100,000 live births and top 45 countries (right side) with 1,000 and above number of maternal deaths in 2020.

- Countries whereby the maternal mortality ratio figure is larger than the number of maternal deaths.

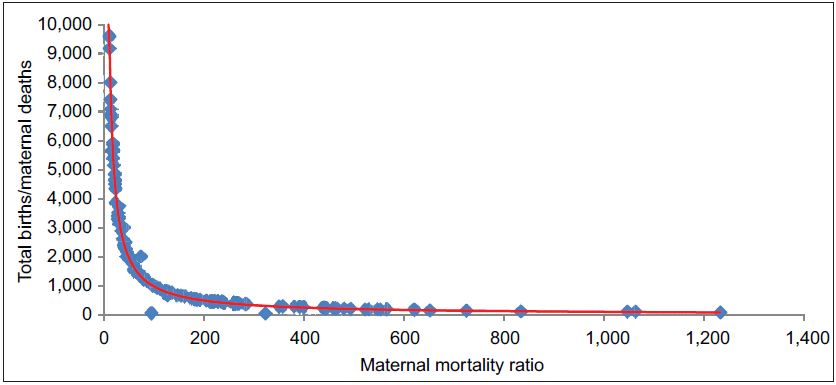

- The effect of total births on maternal mortality ratio (MMR) estimates (ignoring the stillbirths, which was 1.9 million or 0.001% of annual global deliveries). A small increment in maternal deaths in countries with relatively lower number of births “exaggerates” the MMRs. Note that countries with very low (<20/annum) maternal deaths were excluded from this analysis for clear visibility of the graph as they pull the total births to maternal deaths ratio up to 90,000 and makes the lower values congested. The total births to maternal deaths ratio are computed against the maternal mortality ratio (red line- curved and blue dots). Source: UN inter-agency group report. A neglected tragedy: the global burden of stillbirths. 2020.

![Countries those contributed to two-third (more than 67%) of maternal deaths globally in 2000 (left side) and 2020 (right side). Bangladesh, China, and Angola were no more on the leading list, but were not too far from the lead pack [Figure 3].](/content/159/2024/13/1/img/IJMA-13-g7.png)

- Countries those contributed to two-third (more than 67%) of maternal deaths globally in 2000 (left side) and 2020 (right side). Bangladesh, China, and Angola were no more on the leading list, but were not too far from the lead pack [Figure 3].

Acknowledgments

None.

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Financial Disclosure

Nothing to declare.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Declaration of Patient Consent

Patient’s consent is not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Assisted Technology for Manuscript Preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

None.

Funding/Support

There was no funding for this study.

REFERENCES

- Improving pregnancy outcomes in low- and middle-income countries. Reprod Health. 2018;15(Suppl 1):88.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015 estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, world bank group and the United Nations population division executive summary. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. [Accessed 2023 Nov 1]. Available from: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/monitoring/2015

- Maternal mortality in 2000: Estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, and UNFPA. [Accessed 2023 Nov 1]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/68382/a81531.pdf?sequence=1

- Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2008. Estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, the world bank. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

- Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2010. WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, the world bank estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012.

- Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2020: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, world bank group and UNDESA/population division. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023.

- Trends and causes of maternal mortality in Ethiopia during 1990–2013: Findings from the global burden of diseases study 2013. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):160.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Maternal mortality. In: Diseases and mortality in sub-saharan Africa (2nd ed). United States: National Library of Medicine; 2006. Ch. 16

- Maternal mortality for 181 countries, 1980–2008: A systematic analysis of progress towards millennium development goal 5. Lancet. 2010;375(9726):1609-23.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]