Translate this page into:

Cesarean Section and Maternal-fetal Mortality Rates in Nigeria: An Ecological Lens into the Last Decade

*Corresponding author email: hamisu.salihu@bcm.edu

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background or Objectives:

Despite the global decline in maternal mortality within the last decade, women continue to die excessively from pregnancy-related complicationsin developing countries. We assessed the trends in maternal mortality, fetal mortality and cesarean section (C-Section) rates within 25 selected Nigerian hospitals over the last decade.

Methods:

Basic obstetric data on all deliveries were routinely collected by midwives using the maternity record book developed for the project in all the participating hospitals. Trends of C-Section Rates (CSR), Maternal Mortality Rates (MMR), Fetal Mortality Rates (FMR) and Spontaneous Vaginal Delivery rates (SVD) were calculated using joinpoint regression models.

Results:

The annual average percent change in CSR was 12.2%, which was statistically significant, indicating a rise in CSR over the decade of the study. There was a noticeable fall in MMR from a zenith of about 1,868 per 100,000 at baseline down to 1,315/100,000 by the end of the study period, representing a relative drop in MMR of about 30%. An average annual drop of 3.8% in FMR and 1.5% drop in SVD over time were noted over the course of the study period.

Conclusion and Global Health Implications:

We observed an overall CSR of 10.4% and a significant rise in CSR over the 9-year period (2008-2016) of about 108% across hospital facilities in Nigeria. Despite the decrease in MMR, it was still high compared to the global average of 546 maternal deaths per 100 000 livebirths. The FMR was also high compared with the global average. The MMR found in this study clearly indicates that Nigeria is far behind in making progress toward achieving the Sustainable Development Goal 3 (SGD 3) which aims to reduce the global MMR to less than 70 per 100 000 live births by 2030.

Keywords

Cesarean section

Maternal mortality

Fetal mortality

Spontaneous vaginal delivery

Trends in MMR

Nigeria

1. Background and Introduction

Despite the global decline of 45% in maternal mortality from 1990 to 2015, women continue to die excessively from pregnancy-related complications.1 Developing countries account for the majority of these deaths, where the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) is 14 times as high when compared to developed nations.1 Some improvement in MMR within the least and less-developed countries were noted between 2000 and 2012 during which a substantial decrease in MMR occurred, plummeting from 607 and 288/100,000 live births to 432 and 175/100,000 live births, respectively.2 Although a decrease in MMR was also observed in developed countries, it was relatively modest.2 Nigeria has made significant efforts in trying to reduce its unacceptably high MMR, even though it was not able to achieve the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 5 which targets improvement in maternal health. The Nigerian National Population Commission revealed an MMR of 800/100,000 in 2003 which dropped to 574/100,000 in 2013.3 However, these figures are far below, and mask the substantially higher MMR recorded in many Nigerian health facilities.4,5

Globally, Cesarean Section Rates (CSRs) have risen considerably over the past decades. In 2000, the world CSR ranged from 2% in least developed countries to 19.5% in developed countries, with an average of 12%.2 In Nigeria, CSRs have been reported to be as low as 0.9% to as high as 22.57% across different hospital facilities.5 A systematic review of ecological studies revealed that CSR of 9-10% is the threshold beyond which an increase in CSR does not lead to a further decrease in maternal and infant mortality.6 There are various factors responsible for the different CSRs across countries and hospitals. However, low CSRs may indicate inability of women to access life-saving procedures whilst high CSRs may reflect excessive use of cesarean sections (CSs) and therefore, elevated risk for surgical complications.7 Even though CS is regarded as a procedure with low risk, studies indicate that the risk of maternal death is 3 times as high with CS when compared to vaginal delivery.8,9 Another study involving 183 hospitals across 22 African countries revealed that CS is associated with 50 times as much risk of maternal mortality as in higher income countries.10 In this study, we assessed the trend in maternal mortality and fetal mortality within some selected Nigerian hospitals over the previous decade as well the trend of CSRs in these hospitals. The relationship between CSR and maternal and fetal mortality was also examined.

2. Methodology

In 2007, we established the quality assurance projects in 10 hospitals in Northern Nigeria, five each from Kano and Kaduna States. The project expanded to include five more hospitals from the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja in 2011, and then four more hospitals from Ondo in South Western Nigeria by 2013. The details of the hospitals and the project have been published elsewhere.5,11,12 Basic obstetric data on all deliveries were routinely collected by midwives using the maternity record book developed for the project in all the participating hospitals. These data included age of patient, gestational age, parity, mode of delivery, fetal and maternal outcome as well as pregnancy complications. The Chief Midwife of the project then collected summarized obstetric data monthly from all the participating facilities using summary forms. The summarized data entailed total deliveries, total cesarean sections, total maternal and fetal mortality and total pregnancy complications such as eclampsia, postpartum hemorrhage and obstructed labor. All the data were then centrally collated and uploaded in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Part of the data has been analyzed and previously described.5,11 The following pregnancy outcome indices were derived to assess their trends over time.

2.1. Variable Definitions

Cesarean section rate (CSR) defined as the percentage of deliveries that were via a cesarean section = (Number of cesarean deliveries)*100/(total number of deliveries).

Maternal mortality ratio (MMR) = (Number of maternal deaths)*100,000/(total number of live births).

Fetal mortality rate (FMR) = (Number of fetal deaths)*100/(total number of deliveries).

Spontaneous vaginal delivery rate (SVD) = (Number of spontaneous vaginal deliveries)*100/(total number of deliveries).

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Joinpoint regression was then utilized to estimate and describe temporal changes in CSR, MMR, FMR and SVD over the period of the study13,14. Joinpoint regression is valuable in identifying key periods in time marking changes in the rate of events over time. The iterative model-building process began by fitting the annual rate data to a straight line with no joinpoints, which assumed that a single trend best described the data. Then a joinpoint – reflecting a change in the trend – was added to the model and a Monte Carlo permutation test assessed the improvement in model fit. The process continued until a final model with an optimal (best-fitting) number of joinpoints was selected, with each joinpoint indicating a change in the trend, and an annual average percent change (AAPC) estimated to characterize how the rate was changing within each distinct trend segment.

We also sought to determine correlations among the four pregnancy outcome indices considered in this study (i.e., CSR, MMR, FMR and SVD) in order to detect meaningful relationships using the trend data. A useful test would have been Pearson’s correlation but due to violations of data normality and non-linear patterns of the data over time, we opted for the Spearman rank-order correlation coefficient (rs) instead. Spearman rank-order correlation is a suitable non-parametric measure that captures the strength and direction of the relationship between the variables. In generating the Spearman’s correlation coefficients, we applied bootstrapping iteratively with random sampling and replacement. The justification was that the data at hand reflected considerable degree of variance that needed to be accurately captured in order to obtain minimally biased estimates. All hypothesis testing was two-tailed with a type 1 error rate set at 5%. All the statistical analyses were performed using R (version 3·4·3), Rstudio (Version 1·1·423) and Joinpoint Regression Program 4.6.0.0 (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD).

3. Results

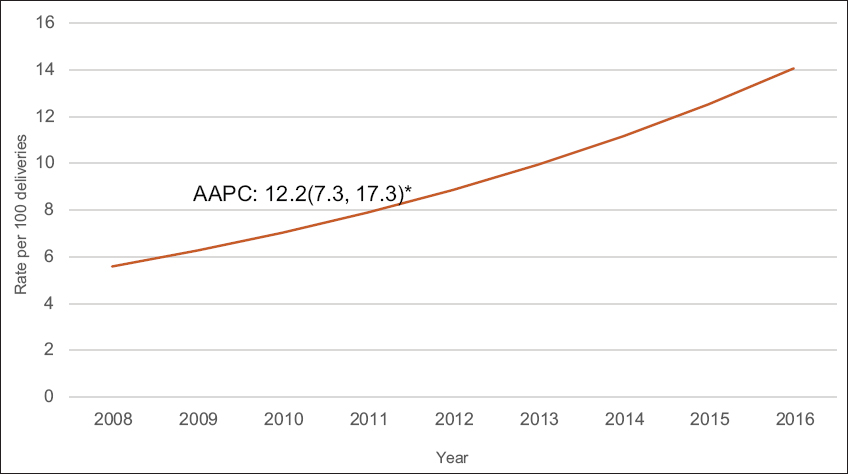

From 2008 to 2016, we recorded a total of 227,583 deliveries across the selected hospital facilities. Of this number, 23,588 were cesarean deliveries, equivalent to a CSR of 10.4%. Total live births over the study period were 211,741 and total number of maternal deaths was 1500 across participating facilities, yielding an overall maternal mortality ratio (MMR) of 708 per 100,000 live births (LB) (Table 1). A total of 15,842 fetal deaths were counted out of the total deliveries of 211,741, yielding a fetal mortality rate (FMR) of about 7.0%. About 180,429 spontaneous vaginal deliveries were documented, and when compared to the total deliveries of viable pregnancies, the spontaneous vaginal delivery rate (SVD) over the entire period of the study was 79.3%. Details of these findings are provided in Table 1. At baseline, the CSR was 6.6%, which increased significantly over the 9-year period to 13.8% by the end of the study period in 2016. This represented an overall relative increase in CSR of about 108%. Figure 1 displays the results of the joinpoint regression analysis of trends in CSR over time. The annual average percent change in CSR was 12.2%, which was statistically significant.

| Hospital | Code | Delivery | CS | CS% | Spont | Spont% | M.Death | MMR | F.Death | FMR | Live births | Year for which hospital data is available |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B/Gwari | 112 | 10815 | 554 | 5.12 | 8807 | 81.43 | 110 | 1112.68 | 929 | 8.59 | 9886 | 2008-2016 |

| Kafachan | 113 | 16288 | 1658 | 10.18 | 12109 | 74.34 | 65 | 426.99 | 1065 | 6.54 | 15223 | 2008-2016 |

| G/Sawaba | 114 | 14297 | 1028 | 7.19 | 11440 | 80.02 | 105 | 800.37 | 1178 | 8.24 | 13119 | 2008-2016 |

| Samunaka | 115 | 10182 | 1219 | 11.97 | 7320 | 71.89 | 123 | 1424.77 | 1549 | 15.21 | 8633 | 2008-2016 |

| Y/Danstoho | 116 | 28143 | 1827 | 6.49 | 22623 | 80.39 | 56 | 212.37 | 1774 | 6.30 | 26369 | 2008-2016 |

| Gaya | 222 | 17447 | 333 | 1.91 | 14931 | 85.58 | 244 | 1560.30 | 1809 | 10.37 | 15638 | 2008-2016 |

| S/Jidda | 223 | 14314 | 503 | 3.51 | 11448 | 79.98 | 130 | 959.69 | 768 | 5.37 | 13546 | 2008-2016 |

| Sumaila | 224 | 8187 | 227 | 2.77 | 6816 | 83.25 | 186 | 2605.04 | 1047 | 12.79 | 7140 | 2008-2016 |

| Takai | 225 | 8246 | 359 | 4.35 | 7025 | 85.19 | 55 | 748.91 | 902 | 10.94 | 7344 | 2008-2016 |

| Wudil | 226 | 17498 | 609 | 3.48 | 14845 | 84.84 | 271 | 1710.10 | 1651 | 9.44 | 15847 | 2008-2016 |

| Abaji | 330 | 3606 | 521 | 14.45 | 2892 | 80.20 | 6 | 173.81 | 154 | 4.27 | 3452 | 2012-2016 |

| Kwali | 331 | 5627 | 720 | 12.80 | 4644 | 82.53 | 8 | 148.42 | 237 | 4.21 | 5390 | 2012-2016 |

| Kubwa | 332 | 19414 | 4016 | 20.69 | 14567 | 75.03 | 44 | 234.47 | 648 | 3.34 | 18766 | 2012-2016 |

| Karshi | 333 | 7397 | 1180 | 15.95 | 5826 | 78.76 | 10 | 139.26 | 216 | 2.92 | 7181 | 2012-2016 |

| Kuje | 334 | 10630 | 2362 | 22.22 | 7982 | 75.09 | 22 | 213.57 | 329 | 3.10 | 10301 | 2012-2016 |

| SSH Ondo | 441 | 6243 | 893 | 14.30 | 5103 | 81.74 | 7 | 115.70 | 193 | 3.09 | 6050 | 2013-2016 |

| Akure | 442 | 8857 | 1346 | 15.20 | 7296 | 82.38 | 18 | 211.67 | 353 | 3.99 | 8504 | 2013-2016 |

| Owo | 443 | 3510 | 565 | 16.10 | 2747 | 78.26 | 3 | 89.93 | 174 | 4.96 | 3336 | 2013-2016 |

| Mother/child | 444 | 10002 | 2151 | 21.51 | 7024 | 70.23 | 19 | 201.78 | 586 | 5.86 | 9416 | 2013-2016 |

| Iwaro Oka | 445 | 3136 | 294 | 9.38 | 2674 | 85.27 | 7 | 235.06 | 158 | 5.04 | 2978 | 2013-2016 |

| GH Agwu | 551 | 202 | 11 | 5.45 | 183 | 90.59 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 202 | 2016 |

| ESUT | 552 | 1924 | 653 | 33.94 | 1155 | 60.03 | 9 | 489.93 | 87 | 4.52 | 1837 | 2016 |

| Ntasiobi | 553 | 287 | 69 | 24.04 | 211 | 73.52 | 1 | 353.36 | 4 | 1.39 | 283 | 2016 |

| MofC | 554 | 1025 | 386 | 37.66 | 569 | 55.51 | 1 | 99.80 | 23 | 2.24 | 1002 | 2016 |

| Annunciation | 555 | 306 | 104 | 33.99 | 192 | 62.75 | 0 | 0.00 | 8 | 2.61 | 298 | 2016 |

| Overall | 227583 | 23588 | 10.36 | 180429 | 79.28 | 1500 | 708 | 15842 | 6.96 | 211741 | ||

Spont = spontaneous vaginal delivery; CS = cesarean section; M.Death = maternal death; MMR = maternal mortality ratio; F.Death = fetal death; FMR = fetal mortality rate

- Joinpoint regression trends for cesarean section per 100 deliveries

The changes in MMR over time described a trajectory that was opposite that of CSR. There was a noticeable fall in MMR from a zenith of about 1,868 per 100,000 at baseline down to 1,315/100,000 by the end of the study period, representing a relative drop in MMR of about 30%. Figure 2 shows the resulting trend trajectory using joinpoint regression analysis. Overall, there was, on average, a 1.5 per 100,000 drop in the annual MMR across delivery facilities over the study period although this was not statistically significant.

- Joinpoint regression trends for maternal mortality ratio (MMR) expressed per 100,000 live births

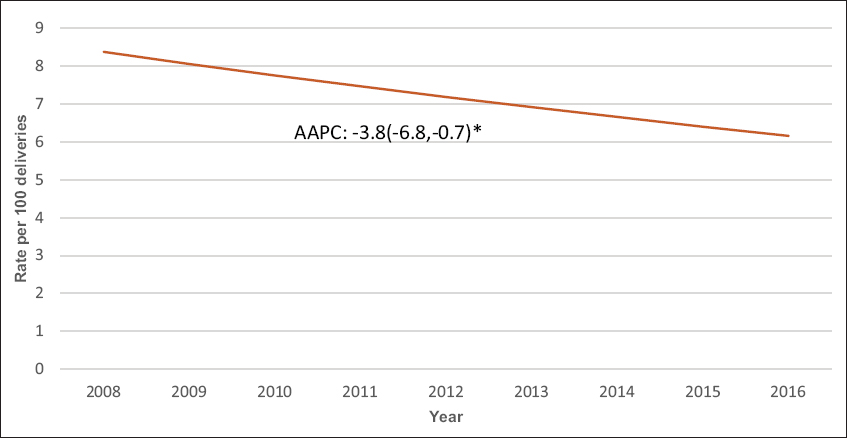

FMR dropped from 8.7 % in 2008 to 6.0% by 2016, corresponding to a total drop of about 30.5% in relative terms. Figure 3 displays the annual average percent change (AAPC) for FMR using joinpoint regression analysis. The findings were significant with an observed average annual drop of 3.8% in FMR over time. Spontaneous vaginal delivery (SVD) rate fell from 89.4% at the baseline year to 81.2% by the end of the study (2016), corresponding to a modest overall decline of about 9.2%. The annual average percent change of 1.5% drop was significant (Figure not shown).

- Joinpoint regression trends for fetal mortality rate per 100 deliveries

Table 2 provides the estimates of correlational analysis among the pregnancy outcome indices (CSR, MMR, FMR and SVD) in a matrix format. Cesarean Section Rates (CSR) demonstrated a strong negative correlation with both FMR and SVD of 67% and 65% respectively with statistically marginal level of significance. Although a positive correlation was displayed between CSR and MMR, this was relatively modest at 23%. The correlation between MMR and FMR was in the same direction but flimsy in magnitude at 7% only. By contrast, MMR and SVD exhibited a much stronger relationship of 65% that showed that the higher the SVD, the lower the MMR. However, this was not statistically significant. Similarly, the negative correlation between FMR and SVD did not attain statistical level of significance (Table 2).

| CSR | MMR | FMR | SVD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR | 1 | rs=0.23; p=(0.55) | rs=-0.67; p=(0.059) | rs=-0.65; p=(0.067) |

| MMR | 1 | rs=0.07; p=(0.88) | rs=-0.63; p=(0.68) | |

| FMR | 1 | rs=-0.67; p=(0.58) | ||

| SVD | 1 | |||

CSR = cesarean section rate; MMR = maternal mortality ratio; FMR = fetal mortality rate; SVD = spontaneous vaginal delivery rate. rs = Spearman’s correlation coefficient; p = p-value

4. Discussion

This ecological study aimed to explore trends in CSR as well as indices of maternal-fetal mortality captured as MMR (maternal mortality ratios) and FMR (fetal mortality rates). We observed an overall CSR of 10.4% and a significant rise in CSR over the 9-year period of about 108%. The overall rate found in our study is in agreement with the optimal CSR proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO) set at 10-15%.15 It is, however, arguable what threshold of CSR will yield positive maternal-fetal outcomes within a given setting. We observed an overall MMR of 708 per 100,000 live births and a FMR of 7.0%. The MMR found in this study clearly indicates that Nigeria is far behind in making progress toward achieving the Sustainable Development Goal 3 (SGD 3). This goal aims to reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100 000 live births by 2030.

In addition, the observed MMR was higher than the Nigerian national average of 574/100,0003. Likewise, both maternal and fetal indices were observed to be substantially high compared with those of developed nations. However, it is noteworthy that both the MMR and FMR dropped by about one-third within the study period. The temporal decline in both MMR and FMR was in contrast and probably influenced by the rise in CSR. This hypothesis is supported by the findings of Betran and colleagues using a global cross-sectional ecological study to assess the relationship between method of delivery and perinatal mortality.16 The investigators found that for countries with overall CSR below 15 percent, CSR had negative association with maternal mortality. Conversely, for countries with national CSR above 15 percent, further increase in CSR correlated with higher maternal and perinatal mortality.16 Several other ecological studies also reported similar findings.17-20

However, other studies had conflicting results. A systematic review of ecological studies concluded that CSR ranged from 9 to 16%, and at CSR above this threshold, there was no longer an association between CSR and maternal or infant mortality.6 Further, according to a multi-center study in Finland, variations in CSR were not related to maternal and neonatal outcomes.21 Some other studies have also investigated the relation between CSR and neonatal outcomes but concluded that an increasing CSR did not improve perinatal outcomes.22-24 These findings may, however, not apply to the African settings (such as in this study) in which fetal conditions are typically not among the common indications for cesarean delivery. Cesarean sections in our settings are typically performed to save the mother and not the fetus.

Despite the decrease in MMR in this study, it was still high compared to the global average of 546 maternal deaths per 100 000 livebirths.25 Similarly, the FMR in this study was also high compared with the global average but comparable to those of other African countries.26,27 Maternal deaths in sub-Saharan Africa result from a wide range of indirect and direct causes. Effective and efficient health system, especially during pregnancy and delivery, are strongly related to maternal death.28 CSR in most sub-Saharan Africa is very low and a lot of patients requiring the procedure end up with severe maternal morbidity, and a large number of them die during pregnancy and delivery.19-20 Quality improvement with respect to cesarean section procedures will therefore, go a long way in reducing the high adverse maternal-fetal outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa.

As with all studies, our analysis bears certain limitations worth highlighting. The dataset used for the study encompassed aggregate data amassed from regional hospitals in Nigeria. The data did not and could not take into account all the maternal and fetal deaths that occurred at home. This shortcoming is relevant since it is well known that a significant proportion of deliveries in Nigeria occurs at home.29 It is difficult to estimate the impact of this omission bias on our reported findings because the proportion of MMR and FMR as well as those that would qualify for a cesarean section in home deliveries could not be determined within an acceptable range of accuracy. Perinatal mortality could also not be calculated because babies were not followed up for one week at home, and hence, early neonatal death could not be calculated.

There is also the general limitation of ecological analysis; namely, ecological fallacy, whereby, observations found in aggregate data do not agree with those detected at the individual level. This limits the validity of inferences regarding a causal association between CSR and reproductive health outcomes in the absence of uncontrolled factors and interactions. For example, the rising CSR may be due to changing demographic factors (e.g. elderly primigravidae, obesity, other medical disorders) which were not captured in our study. Nonetheless, our study bears areas of strengths as well including a large sample size that was adequate for an ecological analysis as well as the application of a rigorous analytic approach, namely, Joinpoint regression which was used in the estimation of temporal trends in CSR, MMR, FMR and SVD.

5. Conclusion and Global Health Implications

In this study, we found an overall CSR of 10.4% and a significant rise in CSR over the 9-year period (2008-2016) of about 108% across hospital facilities in Nigeria. There was a decrease in MMR; but this decrease was still substantially high compared to the global average of 546 maternal deaths per 100 000 livebirths. In Nigeria, the FMR was substantially high compared to the global average. The MMR reported in this study is a clear but sad indication that Nigeria lags behind in attempts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goal 3 (SGD 3), namely to reduce the global MMR to less than 70 per 100 000 live births by 2030.These data should spur policy and programmatic efforts aimed at addressing maternal mortality in Nigeria.

Acknowledgement:

None.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interests: None.

Financial Disclosures: None.

Funding Support: Funding for the study was received from the Rotary international.

Ethics Approval: Ethical Approval was obtained from Bayero University Internal Review Board.

References

- The Millennium Development Goals Report 2015 https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/2015_MDG_Report/pdf/MDG%202015%20rev%20(July%201)

- Association between rates of caesarean section and maternal and neonatal mortality in the 21st century:a worldwide population-based ecological study with longitudinal data. BJOG. 2016;123:745-753.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2013. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICF International;

- Prevalence and Risk Factors for Maternal Mortality in Referral Hospitals in Nigeria. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;143(S3):498. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12582

- [Google Scholar]

- Experiences of 6 years quality assurance in obstetrics in Nigeria –a critical review of results and obstacles. J. Perinat. Med. 2016;44(3):301-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- What is the optimal rate of caesarean section at population level?A systematic review of ecologic studies. Reprod Health. 2015;12:57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Caesarean delivery and neonatal mortality rates in 46 low- and middle-income countries:a propensity-score matching and meta-analysis of Demographic and Health Survey data. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:781-791.

- [Google Scholar]

- Maternal death and caesarean section in South Africa:Results from the 2011-2013 Saving Mothers Report of the National Committee for Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths. S Afr Med J. 2015;105(4):287-291.

- [Google Scholar]

- Maternal mortality and cesarean delivery:an analytical observational study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36(2):248-53. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0756.2009.01125

- [Google Scholar]

- Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes after Caesarean Delivery in the African Surgical Outcomes Study:a 7-day prospective observational cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7:513-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Obstetric quality assurance to reduce maternal and fetal mortality in Kano and Kaduna State hospitals in Nigeria. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2011;114(1):23-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Maternal and fetal mortality and morbidity in hospitals in Kano State and Kaduna State, Nigeria:considerations of prevention and management. Publication University Giessen 11.06.20121. http://geb.uni-giessen.de/geb/volltexte/2012/≉/index.html

- [Google Scholar]

- Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19(3):335-351.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2016. Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 4.2.0.2, Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch, Surveillance Research Program. http://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/

- Rates of caesarean section:analysis of global, regional and national estimates. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2007;21:98-113.

- [Google Scholar]

- Searching for the optimal rate of medically necessary cesarean delivery. Birth (Berkeley, Calif). 2014;41:237-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Caesarean section rates in the Arab region:a cross-national study. Health Policy Plan. 2004;19:101-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Maternal mortality, stillbirth and measures of obstetric care in developing and developed countries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;96:139-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association between rates of caesarean section and maternal and neonatal mortality in the 21st century:a worldwide population-based ecological study with longitudinal data. BJOG. 2016;123(5):745-753.

- [Google Scholar]

- Variation in cesarean section rates is not related to maternal and neonatal outcomes. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013;92:1168-1174.

- [Google Scholar]

- Caesarean delivery rates and pregnancy outcomes:the 2005 WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health in Latin America. Lancet. 2006;367:1819-29.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hospital primary cesarean delivery rates and the risk of poor neonatal outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:721-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of obstetric care and risk-adjusted primary cesarean delivery rates. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:402-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030:a systematic analysis by the UN Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group. Lancet. 2016;387:462-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Elective Delivery at Term after a Previous Unexplained Intra-Uterine Fetal Death:Audit of Delivery Outcome at Tygerberg Hospital, South Africa. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Estimates developed by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. New York, NY: UN Children's Fund 2017; https://www.unicef.org/publications/files/Child_Mortality_Report_2017;

- Factors associated with maternal mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa:an ecological study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:462.

- [Google Scholar]