Translate this page into:

Trends in Stillbirths and Stillbirth Phenotypes in the United States: An Analysis of 131.5 Million Births

∗Corresponding author email: deepa.dongarwar@bcm.edu

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

We examined the trends in stillbirth across gestational age in the United States (US).We conducted a trend analysis using the U.S. Natality and Fetal Death datasets covering 1982 and 2017. We compared the incidence and rates of stillbirth for term, all preterm, moderate-to-late preterm, very preterm, and extreme preterm phenotypes. The incidence of stillbirth decreased for the entire birth cohort over the 36-year period. The rates of overall, term, all preterm, very preterm and moderate-to-late preterm stillbirth decreased from 1982 to 2017; however, the rates for extreme preterm stillbirth increased by about 7.6% over the same study period.

Keywords

Trends in stillbirth

Stillbirth phenotypes

Stillbirth in US

1. Introduction

Intrauterine death of the fetus at or after 20 weeks of gestation or stillbirth is an important reproductive health indicator, and a significant public health problem.1 Stillbirth rates in the United States (US) are higher than in many other industrialized countries; the declining rates of stillbirths in other high-income countries suggest there may be opportunities in the US for improvement.2 The risks and causes of stillbirth vary across the various gestational age categories throughout pregnancy. Applying pre-specified and conservative criteria, about 25% of stillbirth cases that occur in the US are potentially preventable.3 Globally, prematurity is the leading cause of death in under-five children.4 Studies have shown that pregnancies longer than 39 weeks might lead to stillbirth.5 Although the risk of stillbirth usually goes down after 20 weeks, multiple factors contribute to the risk including maternal age, race, socio-economic status, smoking, certain medical conditions such as obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, multiple pregnancies and a history of pregnancy loss.6 Due to the important differences in the risks and causes of stillbirth across gestational age groups, it is important to examine these risks and causes as distinct conditions, which we refer to here as phenotypes. The aim of this temporal trends analysis was to assess the incidence and rates of stillbirth across various gestational age groups.

2. Methods

This was a population-based retrospective cohort study for the years 1982 through 2017, covering a total of 36 years. The Natality data and Fetal Death data files used for the analysis were compiled by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), and made publicly-available by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) using National Vital Statistics System (NVSS), which is the oldest system used to register all vital events such as births, deaths, marriages, divorces and fetal deaths.7 The Birth Data contain information regarding all births occurring in the US irrespective of the residence status, whereas the Fetal Death data contains information regarding all fetal deaths. The Fetal Death data files are available only from the years 1982 through 2017. We restricted our study to singleton births within gestational age 20 - 42 weeks. We classified the gestational age of the fetus into the following categories: (1) all preterm: <37 weeks, (2) term: ≥37 weeks, (3) extreme preterm: <28 weeks, (4) very preterm: 28 - 31 weeks, (5) moderate-to-late preterm: 32 - 36 weeks, 6 days. Next, we calculated the rates of stillbirth, overall, and within each gestational category over 36 years. The percentage of stillbirth was also calculated among all births (live and stillbirths). Temporal trends analysis was performed on the rates of stillbirth over the 36 years of the study period.

3. Results

Our study sample contained a total of 131,451,980 births that occurred in the US from 1982 through 2017, out of which 832,406 or about 0.6% (or 6 per 1000) resulted in stillbirth. A total of 14,197,190 or about 10.8% of the total births were preterm, and 4.6% of those resulted in stillbirth. There were 1,176,475 (or 0.9%) extreme preterm births; 1,478,127 (or 1.1 %) very preterm births; and 11,542,588 (or 8.8%) moderate-to-late preterm births. Among all extreme preterm, very preterm, moderate-to-late-preterm pregnancies, 32.8%, 7.2% and 0.9% resulted in stillbirth, respectively. There were 117,254,790 (89.2%) term births and the incidence of stillbirth among term pregnancies was 184,052 or 0.2% (2 per 1000).

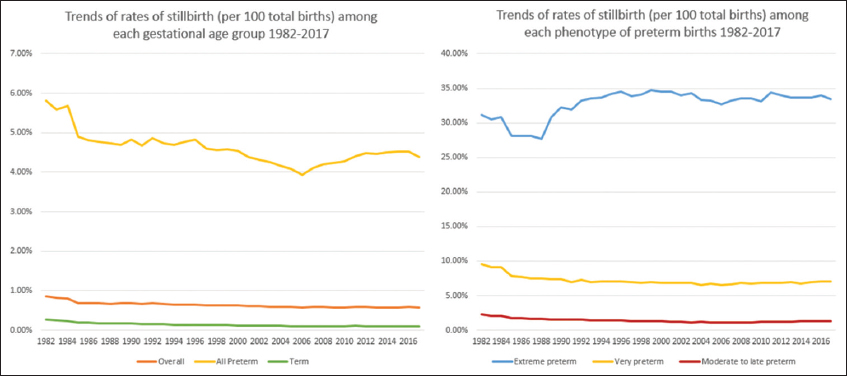

The trends in the incidence of stillbirth across overall, all preterm and term birth categories were very similar, decreasing gradually over the years 1982 to 2017 (Figure 1). Among the phenotypes of preterm birth, moderate-to-late preterm, and very preterm stillbirth decreased over the study period whereas extreme preterm stillbirth decreased from 1982 to 1988, after which it gradually increased over time. The percentage of overall stillbirth among all births (live and stillbirth) went from 0.85% in 1982 to 0.57% in 2017, corresponding to a relative decrease of 32.9% over the years. Similarly, preterm stillbirth rate went from 5.81% to 4.38%, corresponding to a decrease of 24.6% over the years. Very preterm pregnancies reduced from 9.53% to 7.07%, suggesting a 25.9% decrease; whereas moderate-to-late preterm stillbirth rate went from 2.24% to 1.26%, corresponding to an overall reduction of about 43.5%. The maximum reduction in stillbirth rate was observed among term pregnancies, which reduced by 63.3% (0.27% in 1982 to 0.10% in 2017). The only upsurge in stillbirth rate was among extreme preterm stillbirth which increased by about 7.6% (from 31.10% in 1982 to 33.46% in 2017).

- Trends of stillbirth across various gestational age groups 1982-2017

4. Discussion, Conclusion and Global Health Implications

The rates of stillbirth declined across all phenotypes of gestational age over the years 1982 – 2017, except for the extremely preterm phenotype. There was an increase in the rates of stillbirth among the preterm (4.11% to 4.38%), extremely preterm (33.26% to 33.46%), very preterm (6.62% to 7.07%) and moderate-to-late preterm (1.07 to 1.26%) groups in the last 10 years from 2007 to 2017, which is concerning. It has been shown that many stillbirths are potentially preventable and a study found that the most common cause of potentially preventable stillbirths was placental insufficiency, followed by maternal medical disorders, hypertensive conditions and spontaneous preterm birth.2 Our analysis tends to suggest differential stillbirth risk profiles across gestational age categories, and hence, the use of stillbirth phenotypes seems appropriate. Given that the causes of stillbirth are heterogeneous depending on gestational age, more studies are needed to delineate the multi-factorial etiologies of stillbirth by phenotypes.

To decrease the stillbirth rates in the US, more research is needed to identify women early in pregnancy and utilize robust risk stratification strategies for optimized monitoring and intervention.5 To our knowledge, this is the first study examining temporal trends in the risk of stillbirth across gestational phenotypes over several decades in the US.

Conflicts of Interest: Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding: None.

Ethics Approval: Study was approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

References

- Stillbirth:a review. J ournal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 2004;16(2):79-94. doi:10.1080/14767050400003801

- [Google Scholar]

- Stillbirths:rates, risk factors, and acceleration towards 2030. Lancet. 2016;387(10018):587-603. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00837-5

- [Google Scholar]

- Potentially Preventable Stillbirth in a Diverse U.S. Cohort. Obstetrics &Gynecology. 2018;131(2):336-343. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000002421

- [Google Scholar]

- Neonatal Outcomes After Implementation of Guidelines Limiting Elective Delivery Before 39 Weeks of Gestation. Obstetrics &Gynecology. 2011;118(5):1047-1055. doi:10.1097/aog.0b013e3182319c58

- [Google Scholar]

- Trends in Stillbirth by Gestational Age in the United States 2006–2012. Obstetrics &Gynecology. 2015;126(6):1146-1150. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000001152

- [Google Scholar]

- Obstetric Care. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2017. p. :229-235. doi:10.1017/9781316662571.026

- NVSS - National Vital Statistics System. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/index.htm Accessed January 21 2020