Translate this page into:

The Implementation of a State-wide Rapid Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy as a Best Practice in Primary Care Practices Using an Academic Detailing Approach: Lessons Learned from New York State, United States

* Corresponding author email: Monica_Barbosu@URMC.Rochester.edu

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background:

New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute policy recommends that primary care clinicians should initiate same-day-antiretroviral treatment (ART) of a new HIV diagnosis or at the next clinical visit as the standard of care. However, non-HIV-specialized primary care clinicians might not be sufficiently trained to initiate a specialized ART with a newly HIV diagnosed patient. We assessed clinicians’ knowledge and attitudes toward the rapid initiation of ART and provided academic sessions as a training method to guide clinicians through the implementation of a new standard of care.

Methods:

A Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant, online survey was sent to primary care clinicians to assess their knowledge and attitudes towards Rapid Initiation of ART (RIA). We provided personalized academic detailing sessions, addressing questions and concerns gathered from both the initial survey and the individual pre-assessment questionnaire completed prior to the sessions.

Results:

The survey was initially distributed in February 2019, followed by 4 weekly reminders. Approximately 585 providers completed the survey. Subsequently, 552 health care providers from 25 out of 62 counties in NY State were detailed between March 2019 and March 2021. Lessons learned from the sessions included the identification of pragmatic strategies that could be used in the design of effective detailing sessions, followed by enhanced clinical knowledge, which improved patient care.

Conclusion and Global Health Implications:

Inconsistencies in the current testing practices result in missed HIV diagnoses and an increased risk of HIV transmission. Academic detailing-training techniques can be used to respond to clinician-identified key issues/attitudes that may result in a new intervention, suggesting a promising approach in addressing the implementation barriers of of rapid-treatment initiation as the standard of care. The academic detailing approach can be easily adapted and can be beneficial in global public health, HIV/ AIDS control, and other conditions that require a medical practice change.

Keywords

HIV

New York State

Rapid-initiation Treatment

Best Practice

Academic Detailing

Public Health

Global Health

1. Introduction

1.1. Background of the Study

The HIV epidemic increased in a rapid and sustained pattern, and by 1980, had extended to the entire world. By 1983, New York City was the epicenter of HIV infection in the United States. That same year, the AIDS Institute (AI) was created within the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) to coordinate the state’s efforts to fight the growing epidemic.1 In this context, the NYS governor announced a very ambitious three-point plan (i.e., End the AIDS Epidemic [ETE], 2014) to continue the fight against HIV infection the end of 2020. In October 2019, the NYSDOH AI endorsed the initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) on the day of an HIV diagnosis or at the first clinical visit (primary care level); this initiative is to act as the recommended standard of care for HIV treatment in NYS. This recommendation follows the NYS Clinical Guidelines and recommendations of the International Antiviral Society (IAS)-USA Panel. Also, the rapid access to ART supports the “Undetectable equals Untransmittable” (U=U) message. Viral load suppression (VLS) prevents sexual transmission of HIV. Rapid Initiation of ART (RIA) results in earlier VLS than the standard HIV treatment, minimizing the risk of further transmission.2 Based on this evidence and considering early treatment as a critical intervention to end the HIV epidemic in the state, the NYSDOH AI recommends RIA for all newly diagnosed patients. Furthermore, primary care clinicians are encouraged to offer RIA, preferably on the same day of diagnosis or at the next clinical visit to all individuals who are candidates for rapid ART initiation.3

1.2. Objectives of the Study

Both medicine and technology advance at a remarkable speed; new science, drugs, technologies, and guidelines are frequently released. The latest information needs to immediately reach the clinician and be delivered in ways that can be easily fitted in the clinician’s busy schedule. To bring the newest and relevant data to clinicians in an unintrusive manner, Jerry Avorn and Stephen Soumerai introduced (over 30 years ago) the concept of Academic Detailing as a “method of educational outreach that provides prescribers with accurate, non-commercial, and relevant data on medications in a user-friendly, interactive format that is proven to change practice.”4

While other methods for continuing medical education might improve medical knowledge, they do not seem to be sufficient for creating meaningful changes in the clinicians’ medical practice. Conversely, despite the easy and convenient access to information that we experience nowadays, we continue to observe the struggles of well-intentioned clinicians in their quests to change their practices. Paradoxically, clear and well-established guidelines are critical in public health, especially when pertaining to HIV management; patients do not always receive the recommended care, suggesting that knowledge and intentions for changing medical practice (by themselves) are insufficient for changing clinical behavior. The challenges seem to rely on how to effectively integrate health care delivery and public health efforts to improve outcomes.5

Academic detailing sessions are created for health care professionals as non-commercial, unbiased, and short, educational sessions, conducted by physicians, pharmacists, or nurses. The use of this educational modality is based on the idea that better-informed health care providers offer high-quality care to their patients. Therefore, clinicians that are updated in the use of latest, best practices can assist a newly-HIV-diagnosed patient to timely and optimally achieve viral suppression, while reducing HIV-related morbidity and mortality, resulting in the achievement of ETE goals.

The aims of our 15-minute academic detailing sessions were to (i) offer primary care clinicians and non-HIV specialists scientific evidence that supports the importance of rapid-ART initiation on any patient after the immediate diagnosis of a positive result and (ii) provide guidelines on rapid-HIV-treatment initiation. The purpose of this paper is to share our experience related to the use of the academic detailing approach as an effective tool for informing healthcare providers about new public health initiatives and best practices in an effort to change clinicians’ behavior and improve patient care.

1.3. Specific Aims

In efforts to outreach the diverse healthcare workforce in New York State and promote the implementation of the rapid initiation of treatment by the primary care clinicians, the AIDS Institute used different approaches, one of them being academic detailing.

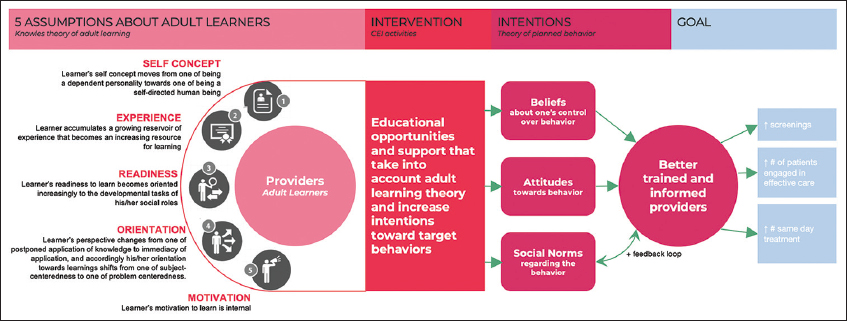

An academic detailing approach integrates health care delivery strategies and public health efforts to improve health outcomes.5 Academic detailing involves personal, targeted interaction with clinicians and their team, ideally provided on-site, at the clinician’s practice location. We adapted Knowles’ Theory of Adult Learning along with the Theory of Reasoned Action and Transtheoretical Model of Health Behavior Change into a pragmatic model of clinician behavior change (Figure 1) that guided the program development and implementation.6,7 Knowles’ Theory guides the strategy of behavior change for clinicians in providing principles maximizing adult learning potential that include self-direction, experience, relatedness, and problem-solving.6 The Theory of Reasoned Action postulates that the learner’s intention, formed by weighing costs and benefits of the intended behavior, drives change,8 and coupled with the staged deployment of intervention appropriate for a learner’s level of readiness (i.e., the Transtheoretical Model of Health Behavior Change), learners are provided with material that they value, that they are ready for, and that leverages their experience and interests.

- Rapid Initiation of ART Logic and Learner Model

We aimed to create a comprehensive model that integrates adult learning principles with pragmatic behavior change in clinical practice, hence the merge of all three models. Subsequently, the resulting model that guided our program development addresses learning principles and action, which maps to our priorities on training and adoption of rapid assessment practices.

In efforts to reach the diverse healthcare workforce in NYS and to promote the implementation of the rapid-treatment initiation by primary care clinicians, the AIDS Institute used different approaches, with academic detailing as one of these approaches.

2. Methods

To assist us in developing the academic detailing strategy, we first conducted a Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliant online survey, using REDCap tools hosted by the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry.9,10 The researchers used a 14-question survey aimed to assess the practice, knowledge, and willingness of NYS clinicians regarding rapid-ART initiation for patients newly diagnosed with HIV.11 Our target audience was primary care providers and non-HIV specialists in NYS: physicians (MD, DO), nurse practitioners (NP), physician assistants (PA), and certified nurse- midwives (CNM) who worked in internal medicine, family medicine, obstetrics, gynecology, and pediatrics; these clinicians also worked in multiple settings, such as private practices, community clinics, college health centers, academic clinics, and hospitals. The survey was distributed in February 2019 and was followed by 4 weekly reminders.

We developed the academic detailing sessions based on the survey results. The training focused on primary care clinicians (i) who would not consider offering a rapid-initiation treatment to a newly-HIV-diagnosed patient and (ii) on their reason(s) for not offering a rapid-initiation treatment. In addition, we developed an RIA kit, comprised of an informative set of materials and resources related to HIV testing, rapid-initiation treatment, and genotypic resistance testing based on the NYSDOH HIV clinical guidelines and recommendations. To further support primary care clinicians in the adoption of this new, public health recommendation, we also created a dedicated website (www.nysria.org) and offered a toll-free phone number.

In developing the academic detailing sessions, we used a team-based approach, built on the latest NYSDOH AIDS Institute HIV guidelines and motivational interviewing techniques as a collaborative, person-centered strategy to generate changes in providers’ clinical practice and to assist them in the implementation of recommended/new guidelines. After anticipating hectic schedules, we used a variety of methods to identify and contact clinicians and to effectively schedule a detailing visit, which included the following: reviewing clinicians’ directories, internet searches, and cold calls; we also took advantage of a “snowballing” process.

To better understand clinicians’ baseline knowledge and experience with the rapid initiation of HIV treatment, we designed every academic detailing session to being with a short REDCap pre-assessment questionnaire: (i) Do you offer an HIV test to all of your patients (13 years and older)? (ii) Are you aware of the Rapid Initiation of ART concept/approach? (iii) Would you consider offering a starter prescription for ART to a patient newly diagnosed with HIV?12 Based on the results from the pre-assessment questionnaire, our academic detailers were able to identify clinician’s concerns, and accordingly, translate those concerns into tailored and personalized academic detailing sessions.

We developed an academic detailing logic model, which depicted our approach to change clinician medical behavior (Figure 1). Academic detailing sessions were initially designed as live 15-20-minute interactive conversations with primary care clinicians. We provided the most current information related to rapid initiation of treatment and also addressed the common concerns regarding the financial impact and patient insurance coverage for HIV-related care.

Moreover, we offered evidence-based and pragmatic strategies to assist primary care clinicians and non-HIV specialists in the implementation of a rapid-initiation treatment in their clinical practice settings.

During the academic detailing sessions, we used motivational interviewing techniques as a collaborative, person-centered form of stimulus to make a change.13 We were able to use the results from the pre-assessment questionnaire to assist us in the inclusion of clinicians into one of the four Stages of Change, based on the Transtheoretical Model of Health Behavior Change: pre-contemplation (clinician was unaware of the RIA protocol and the importance of HIV genotype testing), contemplation (clinician was aware, but no implementation steps were taken, nor did they have any HIV-prescribing experience), preparation (clinician had specific objections to genotype testing and/or the prescribing ARV (e.g., lack of resources and information or training), and action (clinician started prescribing HIV medication and genotype testing based on the provided guidelines of the detailing session).14

We used the Transtheoretical Model of Health Behavior Change as a guide to prospectively tailor provider education materials. Academic detailing sessions were initially arranged as individual visits but then expanded into group presentations after we were invited to present at hospitals’ grand-round seminars. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the in-person approach was interrupted in March 2020, affecting our ability to schedule a one-on-one, in- person meeting with clinicians. We transitioned to a distance-based detailing format, by offering live 60-minute webinars (statewide and regional), by providing continuing medical education (CME) accreditation as an incentive, and by engaging in maximal participation.

3. Results

The REDCap survey was answered by 585 health care providers, of whom 41% were prescribers (Medical Doctor [MD] or Doctor of Osteopathy [DO], Physician Assistant [PA], Nurse Practitioner [NP]), working in hospitals (21.7%), state/local health departments (8.9%), substance-use centers (5.9%), private practices (7.9%), community health centers (23.4%) and other clinical settings (32.2%; i.e., urgent care, dental clinics, nursing care facility, VA, correctional facilities, and school/college health centers).

One of the survey’s questions was “Would you consider offering a starter prescription for ART to a patient newly diagnosed with HIV?” To this question, 73.8% of the respondents answered that they would consider offering rapid-initiation treatment, and 26.2% said they would not offer an ART starter prescription. Respondents who reported that they would not offer the HIV rapid treatment to a newly, diagnosed HIV-positive patient offered their reasons as: (i) “I’m not an HIV specialist” (31%), (ii) I/the practice doesn’t have the resources (12.4%), (iii) I refer to a specialist (35.2%), (iv) not comfortable (1.4%), (v) need more information (7.6%), and (vi) other reasons (12.4%).

Another question was “If you had additional resources and training, would you agree to provide same-day treatment for your newly diagnosed patients?” Approximately 56% of the respondents said “yes,” and 20% said “no.”

We based the development of our academic detailing session on the answers provided from the above two questions. We conducted multiple rounds of academic detailing sessions between March 2019 and March 2021, 53 in-person visits, 9 individual Zoom meetings, and 6 webinars, reaching a total of 552 primary health care professionals. While most of the early participants (285 clinicians) were detailed in-person, 9 clinicians were inaccessible because of the NY State weather conditions and were detailed via ZOOM.

Between January 2019 and March 2019, we conducted 14 in-person visitations and 9 Zoom meetings and detailed 89 health care providers in 21 NYS counties: 41 MDs, 4 PAs, 13 NPs, and 31 others (i.e., PharmD, RN, SW, managers, administrators, and support staff). Between June 2019 and March 2020, we conducted 39 in-person visitations. Approximately 205 health care providers from 25 NYS counties were detailed: 84 MDs, 23 NPs, 8 PAs, and 90 others.

Our pre-COVID experience in providing remote-detailing instruction for inaccessible clinicians prepared us for large-scale implementation once the COVID pandemic restrictions arrived. Therefore, we provided two 60-minute live webinars and detailed 124 primary health care providers (between April 2020 and November 2020): 34 MDs, 9 NPs, 1 PAs, and 80 others who were working in 15 NYS counties. Between December 2020 and March 2021, we offered an additional four regional-live webinars. Approximately 134 health care providers from 17 NYS counties were detailed: 39 MDs, 13 NPs, 3 PAs, and 79 others (Table 1).

| DISCIPLINE | TOTAL | January 2019- March 2019 | June 2019- November 2020 | December 2020- March 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD/DO | 198 | 41 | 84 | 34 | 39 |

| NP | 58 | 13 | 23 | 9 | 13 |

| PA | 16 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 3 |

| Other | 280 | 31 | 90 | 80 | 79 |

| 552 | 89 | 205 | 124 | 134 | |

Because the RIA initiative was originally designed to promote NYS laws and guidelines related to HIV-patient management, it was expected that the majority of the participants were from NYS. However, since the evidence and fundaments for rapid-initiation treatment were applicable to any health care system, we encouraged and allowed providers from all across the country to participate via the webinar sessions. The detailed NYS clinicians received the RIA kit, which included those who were remotely detailed.

4. Discussion

When delivering continuous medical education, it is vital to understand clinicians’ motivations to change their medical practice behavior. Our academic detailers, together with the detailed clinicians, identified key lessons that can potentially be used in the development of future detailing interventions. The REDCap post-session survey showed that the academic detailers played an important role in the provider’s behavior change. The offering of customizable, one-on-one, evidence-based sessions that deliver tailored and relevant messages to clinicians’ patient populations is essential. Also, our use of motivational-interviewing methods proved to be highly effective in constructing provider-specific messaging. In our efforts to reach clinicians and organize the sessions, consistency and flexibility were essential.

Although printed educational materials are becoming obsolete, they still proved to be valuable resources, which were used for reinforcing the information covered during the academic detailing sessions.

We also learned that the implementation of new guidelines, even in the context of state-health-department recommendations, results in less resistance within the private setting (primary care level) compared to hospitals. We attributed this resistance to a more complex and multilevel leadership across the hospital settings, which can play a critical role in the implementation of new health care policies.

Overall, the majority of clinicians strongly agreed with the scientific evidence related to the treatment-implementation advantages of the rapid initiation model as a best practice in HIV care. However, inconsistencies in testing, lack of training, and and unavailable resources are persistent barriers to the implementation of RIA as the standard of care. A few primary care providers were reluctant to start the HIV treatment, arguing that they were not infectious disease specialists; therefore, the patient should be referred to a specialist for treatment initiation. Some primary care clinicians expressed concerns related to RIA implementation at the primary care level, such as (i) a perception of an increased workload that could lead to inconsistencies in following the testing and treatment guidelines; (ii) insurance coverage issues; (iii) treatment cost; (iv) reimbursement issues; (v) lack of resources, including rapid tests at the point-of-care (POC); (vi) long distances to the specialized facilities (e.g., laboratory, pharmacy, and referral offices); (vii) lack of available antiretroviral drugs at local pharmacies, and (viii) a lack of drug samples. We also learned that some primary care physicians do not feel comfortable asking patient’s consent for HIV testing, and did not feel comfortable with asking for patient’s consent in HIV testing, and the physicians did feel comfortable in delivering an HIV-positive test result. Even clinicians who considered the initiation of the rapid treatment perceived patient-treatment adherence as a major challenge to RIA implementation in the primary care setting.

5. Conclusion and Global Health Implications

Academic detailing sessions tailored to address clinician-identified key issues and attitudes toward a complex and new public health intervention may represent one of the best approaches in addressing the persistent barriers to the implementation of a new standard of care. As the sessions are designed to be short training, they deliver the latest updates related to a specialized topic, such the HIV patient care management, in a quick and unintrusive manner.

Extensive research has shown that many non-clinical factors can influence a clinician’s treatment decisions as habits, peer influence, attitude toward disease, time constraints, or economic incentives. All should be considered when designing an educational session.15 We learned that when the academic detailer was able to engage with the clinician in discussions, there was a probability improvement in clinical behavior changes. Printed materials alone have minimal effect on clinical behavior change; however, they are important tools that reinforce the rapid initiation of ART detailing when used as supporting materials.16

The providing of noncommercial, unbiased, and evidence-based information to clinicians can produce sustainable practice change. Academic detailing proved to be a powerful tool that can be used to convey important public-health messages that can translate into medical practice change and patient-care improvement. By using this approach, we were able to gather providers’ feedback that might be useful in the development of future initiatives and programs for the public health environment.

The use of academic detailing for disseminating public health initiatives demonstrated to be a practical approach for promoting new guidelines and best practices among primary care clinicians and for encouraging clinicians’ medical, behavioral change. The option of academic detailing for health care professionals in their training programs, such as medical residency, physician assistant, and nursing, may be an alternative method that can be easily implemented as a new public-health initiative.

The academic detailing approach, used as a way to inform clinicians about the latest and best medical practices, can be beneficial in global public health efforts by addressing existing and emerging conditions that call for continuous, medical practice changes.

Acknowledgments:

The manuscript has not been published, accepted, or under simultaneous review for publication elsewhere. All authors revised and commented on the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no relevant conflict of interest to disclose.

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Funding/Support: This work was supported and funded by the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute, contract DOH-058388-006.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Disclaimer: None

References

- HIV/AIDs Timeline. National Prevention Information Network. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published October 21. 2020. https: //npin.cdc.gov/ pages/hiv-and-aids-timeline#1980

- Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Department of Health and Human Services. https: //clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/sites/default/files/guidelines/documents/guidelines-adult-adolescent-arv.pdf

- Rapid Initiation of HIV Antiretroviral Therapy. NYC Health. Published October 20, 2019. https: //www.health. ny.gov/diseases/aids/providers/treatment/docs/dear_colleague_1030

- Principles of educational outreach ('academic detailing') to improve clinical decision making. JAMA. 1990;263(4):549-556. doi:10.1001/jama.1990.03440040088034

- [Google Scholar]

- Evidence for and implementation of academic detailing. In: Weekes L, ed. Improving Use of Medicines and Medical Tests in Primary Care. Vol 2020. Singapore: Springer; p. :83-105.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Adult Learner:A Neglected Species (3rd ed). Houston: Gulf Publishing; 1984.

- Theory in a Nutshell. McGraw-Hill Education Australia; 2010.

- Evaluation and application of andragogical assumptions to the adult online learning environment. J Interact Online Learn. 2007;6(2):116-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Research electronic data capture (REDCap) –A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-81. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

- [Google Scholar]

- The REDCap consortium:Building an international community of software partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

- [Google Scholar]

- REDCap. https: //redcap.urmc.rochester.edu/redcap/ surveys/?s=NRANMLRJ7Y

- REDCap. https: //redcap.urmc.rochester.edu/redcap/ surveys/?s=3EA9HXAHCY

- Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. Am Psychol. 2009;64(6):527-37. doi:10.1037/a0016830

- [Google Scholar]

- The transtheoretical model and stages of change. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath KV, eds. Health Behavior:Theory, Research, and Practice Vol 2015. (5th ed). Jossey-Bass Wiley; p. :125-148.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physician motivations for nonscientific drug prescribing. Soc Sci Med. 1989;28(6):577-582. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(89)90252-9

- [Google Scholar]

- Changing physician behavior with implementation intentions:closing the gap between intentions and actions. Acad Med. 2016;91(9):1211-1216. doi:10.1097/acm.0000000000001172

- [Google Scholar]