Translate this page into:

Role of Social Determinants of Health in Widening Maternal and Child Health Disparities in the Era of Covid-19 Pandemic

*Corresponding author email: deepa.dongarwar@bcm.edu

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0) which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work, first published in this journal, is properly cited

Abstract

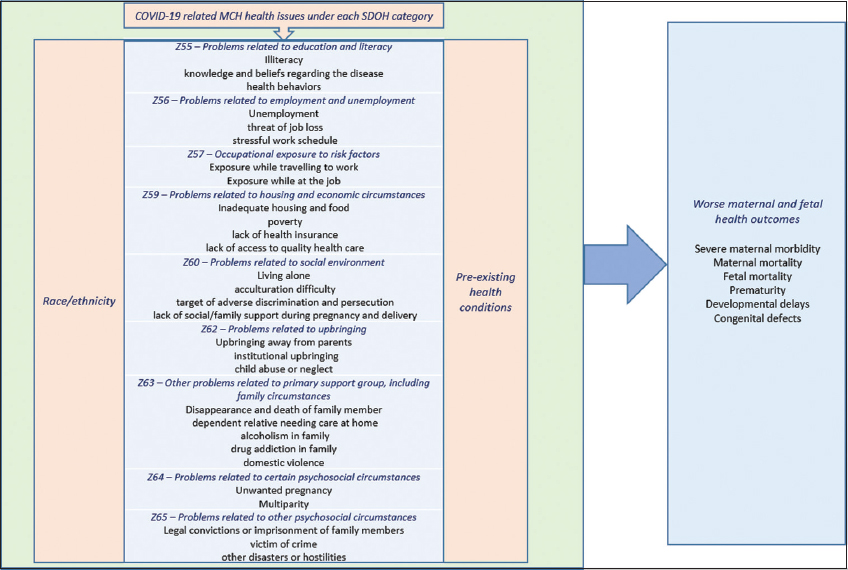

We present a conceptual model that describes the social determinants of health (SDOH) pathways contributing to worse outcomes in minority maternal and child health (MCH) populations due to the current COVID-19 pandemic. We used International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10) codes in the categories Z55-Z65 to identify SDOH that potentially modulate MCH disparities. These SDOH pathways, coupled with pre-existing comorbidities, exert higher-than-expected burden of maternal-fetal morbidity and mortality in minority communities. There is an urgent need for an increased infusion of resources to mitigate the effects of these SDOH and avert permanent truncation in quality and quantity of life among minorities following the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords

COVID-19

Maternal and child health disparity

Social determinants of health

Minority women

1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and the resulting condition, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has had a devastating societal effect with alarmingly high infection and case fatality rates (CFR). Among all COVID-19 deaths in the United States (US), 38.2% were among women. Moreover, the CFR for women among those with an underlying condition is 37.2%.1 Pregnant women are considered to be a vulnerable population group to infection as a result of immunological changes during pregnancy.2 To date, it is unknown if pregnant women have a greater risk of COVID-19 infection than the general public.3 However, it is known that pregnant women have an increased risk of severe illness when infected with viruses from the same family as coronaviruses such as influenza.3

Although information on maternal-fetal outcomes during the current COVID-19 pandemic among various racial/ethnic groups remains sparse, it is important to consider whether the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic could impose elevated levels of maternal-fetal morbidity and mortality given the known role of social determinants of health (SDOH) in the current pandemic. SDOH are complex circumstances in which an individual is born and lives, that impact their life based on interrelated factors such as their social and economic condition. In this study, we offer a conceptual model that describes the SDOH pathways that may contribute towards disparities and worse outcomes in the maternal and child health (MCH) population during a time of crisis, like the current ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Methods

SDOH has the following components as identified by Healthy People 2020 from the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP): education, economic stability, neighbourhood and built environment, health and health care, and social and community context.4 Based on the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes included in categories Z55-Z65, (also referred to as “Z-codes”), 5 we identified non-medical SDOH factors that may influence a mother’s health status. These Z-codes identify issues related to a patient’s socio-economic situation, including literacy, employment, housing, occupational exposure to risk factors, social and psychosocial circumstances; and tie in with the SDOH model proposed by ODPHP on Healthy People 2020. We delineated the issues that the MCH population could face, under each of the Z-code categories, during stressful times, such as in a pandemic. We then determined how these SDOH pathways could lead to disproportionate impacts of Covid-19 related maternal-fetal morbidity and mortality across racial/ethnic groups with pre-existing conditions as effect modifiers.

3. Results

We created a selective list of concerns, issues, and circumstances that the MCH population might face during the pandemic under each Z-code category (Figure 1). This was a unidirectional framework which included the following components: (1) maternal race/ethnicity, (2) COVID-19 related SDOH issues faced by the MCH population and (3) existing comorbidities. We believe that the combined effect of these 3 factors contribute towards worse MCH outcomes. Issues related to education and literacy (e.g. low levels of health literacy, limited knowledge, and unconventional health beliefs concerning the COVID-19 pandemic including unhealthy lifestyles/behaviors) could place MCH racial/ethnic minorities at higher risk of adverse health outcomes. Issues related to the social environment are important during the current covid-19 pandemic, and could impact minority populations more. Minority women could be targets of adverse discrimination and persecution. In addition, due to stay-at-home orders, they may not have sufficient support from the family and society during pregnancy and delivery. Because of the lockdown, minority pregnant women who do not have a healthy relationship with their spouses or family members may suffer mental health stressors such as domestic violence, substance abuse or traumatic situations like disease or death in the family.6 Other psychosocial factors that might play a huge role in affecting minority women’s life during the pandemic include unwanted pregnancies, multiparity, and incarceration in family, being victims of crime, disasters or other hostilities. Studies have shown that minority women are more likely to suffer from these issues than Whites;7 and these events are more likely to happen during the COVID-19 lockdowns. These underlying SDOH pathways, coupled with pre-existing comorbidities like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, lung disease may result in elevated risk for adverse maternal and fetal outcomes including maternal or fetal mortality, severe maternal morbidity, prematurity, developmental delays and congenital defects among minority populations.

- Conceptual model to describe the social determinants of health pathways contributing towards disparities and worse outcomes in the MCH population during the COVID-19 pandemic

4. Discussion And Global Health Implication

It is observed that the ever-so-common racial/ethnic bias in access to healthcare has become even more prominent during the current COVID-19 pandemic. About 70% of the COVID-19 deaths in Chicago were among African Americans, even though that racial group makes up only a third of the city’s population.8 The reason for this is multi-faceted. Blacks are overrepresented among those living with some of the underlying health conditions that can put a person at risk of becoming seriously ill or dying due to the coronavirus;9 but it has also been found that health care providers are less likely to refer African Americans for COVID-19 testing.10 We believe that this inherent prejudice against the minority groups, along with the SDOH characteristics and pre-existing health conditions could negatively impact mothers and children during this pandemic.

It is noteworthy that a high level of racial segregation exists in large urban counties with worse living conditions in those where minorities reside.11 Adding fuel to the fire was the rumor going around in the early days of the pandemic, that Blacks are immune to COVID-19, 11 which would have encouraged lax attitude towards social distancing and hygiene precautions suggested by authorities. Blacks and Hispanics disproportionately belong to the part of the work force that does not have the luxury of working from home; and that places them at high risk for contracting the highly infectious disease in transit or at work.11 Minority population is also hugely under-insured. It has been reported that nearly half of all Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous women had discontinuous insurance coverage between pre-conception and post-delivery, as compared to about a fourth of White women. 10

The COVID-19 crisis has made the problems associated with maternal and child health even more acute. Pregnancy related health care options such as fertility treatments, access to health care after a miscarriage or options for abortions have become extremely restrictive due to the pandemic. With social distancing guidance in place, antenatal care has become less feasible; and some hospitals have implemented a one-visitor policy in birthing rooms, forcing pregnant women to make an impossible decision of choosing between the partner and a doula or midwife.12 Health equity will not be achieved without addressing implicit bias in health care delivery and working towards harboring racial and SDOH impartiality. COVID-19 might be the trigger that the US needed to tackle disparity in access to health care and to work towards improving the lives of vulnerable minority women and children in the country. There is an urgent need for a massive infusion of resources to mitigate the effects of these SDOH and avert permanent truncation in quality and quantity of life among minorities following the pandemic.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no conflict of interests.

Financial Disclosure: None.

Funding/Support: The publication of this article was partially supported by the Global Health and Education Projects, Inc. (GHEP) through the Emerging Scholars Grant Program (ESGP). The information, contents, and conclusions are those of the authors’ and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by ESGP or GHEP.

Ethics Approval: Study uses publicly available datasets and is deemed exempt.

References

- Coronavirus Age, Sex, Demographics (COVID-19) - Worldometers.info. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/coronavirus-age-sex-demographics/. Published 2020

- The Immune System in Pregnancy: A Unique Complexity. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2010;63(6):425-433. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00836.x

- [Google Scholar]

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/pregnancy-breastfeeding.html. Published 2020

- Social Determinants of Health |Healthypeople.gov. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health. Published 2020

- ICD-10-CM Coding for Social Determinants of Health. https://www.aha.org/system/files/2018-04/value-initiative-icd-10-code-social-determinants-of-health.pdf. Published 2020

- How COVID-19 may increase domestic violence and child abuse. https://www.apa.org/topics/covid-19/domestic-violence-child-abuse. Published 2020

- Racial/Ethnic Differences in Unintended Pregnancy. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2016;50(4):427-435. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.09.027

- [Google Scholar]

- Efforts to Reduce Black Maternal Mortality Complicated by COVID-19. https://www.chcf.org/blog/efforts-reduce-black-maternal-mortality-complicated-covid-19/. Published 2020